38 Degrees

Wednesday, April 6, 2016

James Dennis (University of London)

This case study explores 38 Degrees, a political activist movement based in the United Kingdom that has, since its foundation in 2009, amassed a membership of 2.5 million individuals. Through their use of email and social media, 38 Degrees mobilizes its geographically dispersed membership across sedimentary networks: loose affiliations of digitally connected individuals that periodically come together to act across a diverse range of issue campaigns (Chadwick and Dennis 2014). The group has achieved significant policy change, most notably in their campaign to halt the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government’s plans to sell off public forests in 2011 (Chatterton 2011).

38 Degrees bears little resemblance to the organizational models that scholars in political science have become accustomed to. Unlike political parties or traditional pressure groups, its members play an important role in directing the movement’s day-to-day decision making. Essentially, the organization acts as a conduit for its membership, removing the layers of elite-level decision-making that characterized political groups of the twentieth century.

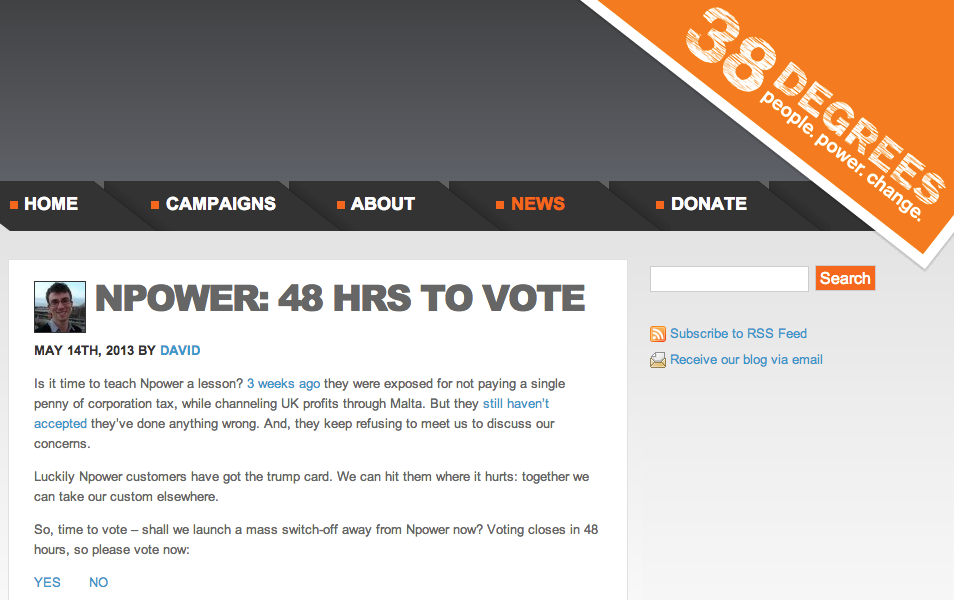

Members are responsible for a number of decisions made throughout each campaign. During the recent campaign to compel a leading energy provider to pay more tax, members were consulted on whether the movement should launch the campaign, their ideas were sought for potential campaign tactics and, as shown in Figure 1, they were given the final say as to whether or not 38 Degrees should try to organize a mass, “people-powered” switch away from the energy provider to alternative suppliers. By using digital tools that are diffused widely amongst its membership, members are able to express their opinion and set the movement’s priorities very quickly on an unprecedented scale. For those involved, this is a clear and visible way of exerting their influence.

However, it is important to emphasize that 38 Degrees is not an example of “organizing without organizations” (Shirky 2008). The staff, based in the organization’s central London office, performs a gatekeeping role and have an enhanced level of influence over the design and selection of campaign actions. Yet, equally, this is not an elite-dominated hierarchy masquerading as being member-driven. The movement relies on the central office to assimilate the priorities of its members and then offer repertoires of engagement. As such, the movement’s overall direction is decided by its membership. Paolo Gerbaudo (2012) describes this as “soft leadership”; the staff organizes and structures campaigns whilst minimizing their encroachment on the will of each individual member.

Karpf (2012) proposes to consider this as characteristic of a new type of organization. These new organizations challenge our traditional conceptions of collective action, as they are structurally fluid. 38 Degrees — like GetUp! in Australia (Vromen and Coleman 2014) and MoveOn in the United States — is an example of a “hybrid mobilization movement,” using the internet to adapt and transform its organizational structure and repertoire of actions during campaigns in real-time (Chadwick 2007, 283). 38 Degrees lacks the bureaucratic structures that make rapid structural change difficult for traditional organizations. By virtue of its structural fluidity and through constant monitoring of members’ attitudes, the organisation is able to strategically adapt and respond to current events, riding the groundswell of enthusiasm and interest that surrounds current affairs (Chadwick 2013, 193). It is this responsivity, coupled with the organization’s fluid structure, which is central to the cultivation of a sense of proximity for the membership, a vital characteristic given its diffuse and networked structure.

A critique frequently leveled at 38 Degrees is that its campaigns amount to little more than clicktivism, low-threshold forms of political engagement online that are perceived to have an insignificant effect on political outcomes (Rickett 2013). It is important to note that the repertoire of actions used by 38 Degrees is not limited to e-petitions or hashtag activism. The organization employs a range of online and real-space engagement repertoires that vary depending on the campaign aims. In the recent campaign to stop the passage of the Transparency of Lobbying, Non-party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Bill, otherwise known as the “gagging law” members were initially tasked with sending an email to Chloe Smith MP, the minister responsible for the bill. The intensity of member participation increased as the campaign progressed, culminating in a rally outside the Houses of Parliament (see Figure 2).

> > When examined in isolation, examples of so-called clicktivism may seem trivial. However, these low-threshold digital acts form an important part of an architecture of participation in which the interdependency between different acts sheds light on the normative value of one’s democratic engagement

(Chadwick and Dennis 2014). For example, in the campaign to pressure a clothes manufacturer to pay compensation to the affected families of the 2013 Rana Plaza factory collapse in Bangladesh, the first action launched was an e-petition — a common practice for most 38 Degrees campaigns. By collating email addresses through an online petition, the central office are able to mobilize a network of engaged members, some of whom will then take part in further activism; in this case a series of localized protests at the company’s stores (Torabi 2014).

It is true that the actions designed by the central office often require small amounts of effort, or more precisely time; they are designed with this in mind. By making campaign actions granular, the organization lowers the barrier of entry to political participation. Past studies have highlighted that the democratic benefits accrued through use of the internet tend to be skewed in favor of affluent, well-educated, and politically informed citizens (Brundidge and Rice 2009; Mossberger, Tolbert and Stansbury 2003). However, 38 Degrees try to buck these trends by enabling non-activists to take action in spheres traditionally controlled by political professionals.

When considering the time pressure that individuals experience on a daily basis, the granularity of digital engagement represents an important means of maintaining awareness — keeping a toe in the water so to speak — sometimes sparking further involvement at opportune moments. These moments tend to revolve around personal context. The membership of 38 Degrees is not tied into one fixed ideology, but instead individuals pick and choose the issue campaigns to which they relate. Individually expressive frames displace more traditional, collective action frames, in what Bennett and Segerberg (2013) describe as “personal action frames.” Political participation is therefore self-motivating, as political acts are akin to personal expression.

What is most striking about the movement is its organizational ethos, “People. Power. Change.” Individual empowerment is at the heart of the movement. In line with those who argue that citizenship is increasingly personally-defined rather than institutionally-derived, and that engagement is focused around issues of importance to the individual rather than coherent ideologies (Dalton 2008; Pattie, Seyd and Whiteley 2004, 275), the successes of 38 Degrees comes down to how the organization maximizes the membership’s sense of efficacy; the feeling that each individual member has, or can have, an impact. The movement offers what people want from their political participation — influence and tangible efficacy, rather than rigid ideological platforms and unresponsive hierarchies.

REFERENCES

Babbs, David. 2013. “NPOWER: 48 HRS TO VOTE.” 38 Degrees. Last Modified May 14, 2013. Accessed May 25, 2013. http://blog.38degrees.org.uk/2013/05/14/npower-48-hrs-to-vote/.

Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg. 2013. The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brundidge, Jennifer, and Ronald E. Rice. 2009. “Do the information rich get richer and the like-minded get more similar?” In Routledge Handbook of Internet Politics, edited by Andrew Chadwick and Philip N. Howard, 144–157. London: Routledge.

Chadwick, Andrew. 2007. “Digital Network Repertoires and Organizational Hybridity.” Political Communication 24 (3): 283–301.

Chadwick, Andrew. 2013. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chadwick, Andrew, and James Dennis. 2014. “’People. Power. Change.’: 38 Degrees and Democratic Engagement in the Hybrid Media System.” Paper presented at the American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, Washington, D.C., August 27–31.

Chatterton, Jonny. 2011. “Victory! Government to Scrap Plans to Sell Our Forests.” 38 Degrees. Last Modified February 17, 2011. Accessed February 28, 2013. http://blog.38degrees.org.uk/2011/02/17/victory-government-to-scrap-plans-to-sell-our-forests/.

Dalton, Russell J. 2008. Citizens Politics: Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies. 5th ed. Washington DC: CQ Press.

Gerbaudo, Paolo. 2012. Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Action. London: Pluto Press.

Karpf, David. 2012. The MoveOn Effect: The Unexpected Transformation of American Political Advocacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mossberger, Karen, Caroline J. Tolbert, and Mary Stansbury. 2003. Virtual Inequality: Beyond the Digital Divide. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Pattie, Charles, Patrick Seyd, and Paul F. Whiteley. 2004. Citizenship in Britain: Values, Participation and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rickett, Oscar. 2013. “Want to change the world? It won’t happen via your mouse button.” The Guardian, November 22. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/nov/22/change-the-world-charity-facebook-e-petition.

Shirky, Clay. 2008. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations. London: Allen Lane.

Torabi, Ali. 2014. “MATALAN: DAY OF ACTION.” 38 Degrees. Last Modified August 4, 2014. Accessed August 10, 2014. http://blog.38degrees.org.uk/2014/08/04/matalan-day-of-action/.

Vromen, Ariadne, and William Coleman. 2013. “Online Campaigning Organizations and Storytelling Strategies: GetUp! in Australia.” Policy and Internet 5 (1): 76–100.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.