An #EpicFail #FTW: Considering the Discursive Changes and Civic Engagement of #MyNYPD

Friday, April 8, 2016

Sarah Whitcomb Lozier (University of California, Riverside)

The focus of this case study is the “hijacking” of the #MyNYPD hashtag by Twitter users on April 22, 2014 (Ford 2014).Over the course of this day, #MyNYPD was used to spread images and tweets of police brutality all over the country. As will become clear throughout this study, this particular instance of “hashtag-activism” changes the terms of this highly criticized form of early twenty-first century political, civic engagement. #MyNYPD demonstrates that, while a hashtag may not be able to effect physical change in the world in the way that a march, a sit-in, a rally, or the act of voting may be able to, it can effect significant change at the level of discourse and rhetoric. That is, this event shows the potential for hashtags and their function throughout digital social media to provide a model of political activism, of civic participation, aligned with staging a conversation, opening a dialog, or delivering a speech.

> > On April 22, 2014, the New York Police Department experienced, first hand, the power of a well-placed (some may say misplaced) hashtag on twitter.

At 10:55 a.m., @NYPDnews tweeted: “Do you have a photo w/ a member of the NYPD? Tweet us & tag it #myNYPD. It may be featured on our Facebook” (NYPD News 2014).

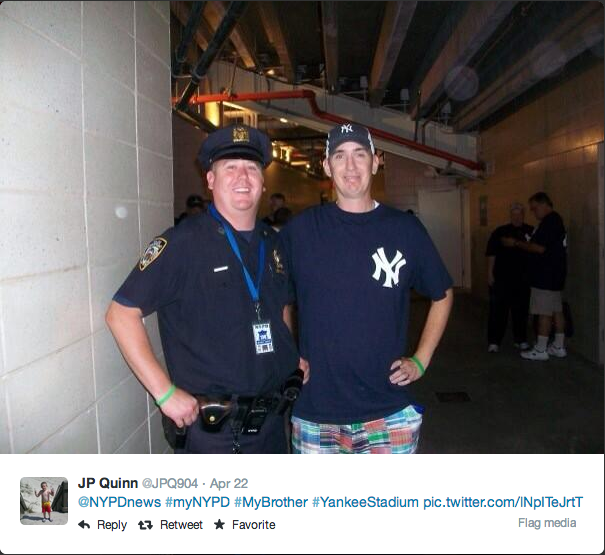

Accompanying the tweet was an image of two NYPD officers and a smiling member of their public, posing for a picture in front of a squad car. As the model photo demonstrates, the expectation of this social media campaign was to elicit photographs of the New York citizenry being protected and served by New York’s Finest. Some Twitter users, like Lindsay Dixon (@poshwonderwoman) and JP Quinn (@JPQ904), responded with the expected photos and tweets. At 11:34 a.m., Dixon provided a picture of herself, smiling, surrounded by three uniformed officers with the 140 character caption: “@NYPDnews my photo from the ride along with the boys from the 90th pct #myNYPD,” (Dixon 2014) and at 10:59 a.m. Quinn tweeted a photo of a delightfully smirking Yankees fan posing with an equally jolly uniformed officer, captioned: “@NYPDnews #MyNYPD #MyBrother #YankeeStadium” (Quinn 2014).

Little more than an hour after @NYPDNews’s original tweet, however, the tide turned as twitter users co-opted the #myNYPD hashtag, mobilizing it to flood Twitter with photos of alleged police brutality. Sincere photos like Dixon’s and Quinn’s were quickly drowned by this continuous wave of violent images accompanied by biting, sarcastic captions. Occupy Wall Street (@OccupyWallStreetNYC), for example, posted an image of an officer in the act of forcefully swinging a baton at protestors with the caption “Here the #NYPD engages with its citizenry, changing hearts and minds one baton at a time. #MyNYPD” (Occupy Wall Street 2014).

Similarly, Casey Aldridge (@CaseyJAldridge) tweeted an image of a man lying on the ground screaming as his leg is trapped under a police motorcycle. The caption accompanying this photo reads, “’And we’re going to have to run you over, just for good measure.’ #MyNYDP” (Aldridge 2014).

By the end of the day, #MyNYPD was the top trending conversation on Twitter, having sparked a viral visualization of police brutality that raged across the country: from #MyNYPD to #MyLAPD and #MyOPD (Oakland), to #MyAPD (Albuquerque) and #MyCPD (Chicago). The original invitation to tweet a photo with a member of the NYPD with the hashtag #MyNYPD became an invitation to “post police brutality photos…that reveal the reality of your local police department, with the hashtag #My(Insert Your Corrupt Police Department Here)” (Methyl 2014).

In what has become known as the NYPD’s comically disastrous #EpicFail, the NYPD did indeed learn a valuable lesson in viral media campaigning or “asking the internet to use a Twitter Hashtag” (Broderick 2014). The lesson, of course, is that police officers may wield power in the physical world where, as the images make clear, they can make and break physical bodies. However, in the virtual world, in the “Twitterverse,” the power belongs to the tweeters, the hasthag users. As has been exhaustively observed in conversations about the relationship between hashtags and political activism — hashtag-activism or slacktivism as it is has been called — the use of a hashtag does not, in itself, have any effect on the physical world. #MyNYPD cannot break bodies like a baton, it cannot blind eyes like pepper spray, and it cannot stop hearts like bullets. Similarly, it cannot revive the bodies and rebuild the lives damaged by these tools, nor can it change the standards and laws governing police weaponry and their use. As Shonda Rhimes succinctly sums it up: “A hashtag does not make you Dr. King. A hashtag does not change anything. It’s a hashtag” (Rhimes 2014). The course of the #MyNYPD event, however, demonstrates the danger of this kind of dismissal for those whose power stands to be usurped by a surge of hashtaggers. Over the course of April 22, 2014, the balance of power shifted: the NYPD was no longer in charge of that hashtag, its meaning, or its usage. Indeed, more than two months after the event, the hashtag continues to be used to tag and signify police brutality rather than civil service.

The pivot in the ability of the hashtag to signify is what marks this event as key in our discussions and considerations of civic media, or civic engagement through digital social media. Over the course of April 22, Twitter users wrested rhetorical and discursive power from the NYPD by changing the meaning of the #MyNYPD signifier. In other words, this event, mobilized by and around a hashtag, is significantly more than just “typing into your computer and going back to binge-watching your favorite show” (Rhimes 2014). It is typing into your computer and changing the very terms of what you have just typed. This is change bound to the level of the abstract and the virtual, certainly, but the abstract and the virtual is precisely the realm where public rhetoric functions, the space where discourse is located. That this iteration of discursive change was accompanied by a shift in power dynamics, an insistence on visibility and transparency, and a form of civic participation, housed in the twitter conversations of young people that spanned and continues to span beyond the United States, only marks it as that much more significant. What may have been an #EpicFail for the NYPD’s public relations team was an #EpicWin for the Twitterverse and its hashtagging “Slacktivists.”

References

Broderick, Ryan. “The NYPD Learned A Very Valuable Lesson About Asking The Internet To Use A Twitter Hashtag.” Buzzfeed, April 22, 2014, 3:22 p.m. http://www.buzzfeed.com/ryanhatesthis/the-nypd-just-learned-a-very-valuable-lesson-about-asking-th.

Casey Aldridge, Casey. Twitter Post. April 22, 2014, 3:30 p.m. https://twitter.com/CaseyJAldridge.

Cassius Methyl. “#MyNYPD Police Brutality Goes Global Worldwide #My(InsertCorruptPD) Twitter Storm Underway.” Blog Post in The Anti-Media. April 23, 2014. http://theantimedia.org/global-police-brutality-twitter-storm/.

Dixon, Lindsay. Twitter Post. April 22, 2014, 11:34 a.m. https://twitter.com/poshwonderwoman.

Ford, Dana. “D’oh! NYPD Twitter Campaign Backfires.” CNN Tech, April 24, 2014. Accessed June 29, 2014. http://www.cnn.com/2014/04/22/tech/nypd-twitter-fail/index.html.

NYPD News. Twitter Post. April 22, 2014, 10:55 a.m. https://twitter.com/NYPDnews.

Occupy Wall Street. Twitter Post. April 22, 2014, 12:12 p.m. https://twitter.com/OccupyWallStNYC.

Quinn, J.P. Twitter Post. April 22, 2014, 10:59 a.m. https://twitter.com/JPQ904.

Rhimes, Shonda. “2014 Dartmouth Commencement Address.” Speech given at Dartmouth College 2014 Commencement, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, June 8, 2014.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.