Another Promise’s Digital Civic Network and Samsung

Friday, March 25, 2016

Chaebong Nam (Cornell Law School) and Hyun-Chol Cho (Seoul National University)

Another Promise is a South Korean film that was released in 2014. It describes how a father seeks justice in the courts after his daughter died of leukemia contracted at a Samsung semiconductor plant where unprotected workers were exposed to toxic chemicals. This film is the first one in Korean cinema history funded entirely by crowdfunding and individual investments. Its success was largely attributed to the key role of digital media in forming digital civic networks among ordinary citizens to gain support through funding, marketing, and distribution.

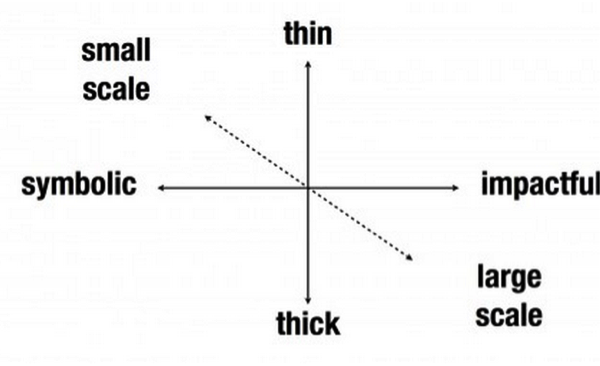

To elucidate this virtually unprecedented digital civic activism in Korea, we can attend to Zuckerman’s two-dimensional matrix for the analytic framework, introduced in the web posting “Beyond the Crisis in Civics”. One axis of the matrix shifts from “thin” to “thick” and the other from “symbolic” to “impactful.” On the first axis, “thin” activities include those of little commitment including signing a petition, clicking “like” on Facebook pages, or retweeting Twitter mentions. “Thick” activities require substantial commitment or action to find solutions such as developing organizing strategies for a political campaign. On the second axis, “symbolic” engagement includes activities of “making voice,” the purpose of which is showing support rather than making an immediate change. “Impactful” engagement, on the other hand, is directed towards concrete results like policy changes. Among the four possible combinations, “thin and symbolic” engagement seems applicable initially to the new civic culture created by digital media, but it also can potentially lead to thick and impactful influences. The transition from the former to the latter is not automatic, though, because thin and symbolic phenomena are likely to be volatile and in many situations remain in echo chambers. Regarding this flow in the matrix, what is interesting about _Another Promise_’s digital civic network in the Korean context is that it illustrates how a particular small voice leaped from “thin and symbolic” to “thick and impactful,” especially that change being made against Samsung, which is perceived in Korea as almost invulnerable.

Phase 1: The First Stage of Crowdfunding and “Digital Flock”

In June 2005, Yun-Mi Hwang, then a 20-year-old woman, was diagnosed with acute leukemia 20 months after beginning work at one of the Samsung semiconductor plants. She died in 2007. Her father, Sang-Ki Hwang, soon began a long legal battle against the world’s largest electronics company, with the intention of proving that his daughter’s death was caused by exposure to toxic chemicals at the plant. Yun-Mi was among the numerous victims beginning in the late 1990s whose deaths were allegedly from the same causes. Still, this event barely drew public attention; Samsung repeatedly denied that the work environment contributed to this fatal disease.

A newspaper article about Yun-Mi’s case inspired the film director Tae-Yun Kim to bring this issue to the screen. Soon after, the best filmmaking staff and crews in Korea volunteered to undertake the project pro bono. The filmmaking team, however, faced an unexpected financial issue resulting from major commercial investors’ abrupt retraction of their investments. This action was presumably due to their reluctance to be involved in a film that was critical of Samsung. The only funding option left for the filmmakers was crowdfunding — originally intended solely for marketing use.

vimeo:

Video 1: The Teaser Trailer for Another Promise from goodfunding on Vimeo

Video 1: The Teaser Trailer for Another Promise from goodfunding on Vimeo

In November 2012, the filmmaking team launched a crowdfunding project using an online platform, Good Funding. Within one month, about $100,000 was gathered from approximately 2,000 people. Ki-Ho Yoon, the film’s producer, said that crowdfunding contributors of the first stage were a group of people who were actively informed and critical of various social issues, and who were already aware of the Samsung workers’ occupational diseases. Attracting the attention of a “digital flock” beyond this small and informed group was a challenge.

Video 2: The Teaser Trailer for Another Promise at the Official Webpage

Video 2: The Teaser Trailer for Another Promise at the Official Webpage

Another Promise_’s filmmaking team initiated a strategic movement to avoid digital echo chambers. In January 2013, Yoon launched an official webpage for a second crowdfunding effort called _The Filmmaking Co-Op, as well launching a Facebook page and a Twitter account. The team hired a media specialist to facilitate not only communication and advertising, but also fundraising.

In February 2013, the filmmakers began to appear on well-known podcasting shows that critically examine controversial issues largely overlooked in the mainstream media. Nonetheless, these podcasting shows drew audiences who might have already participated in the first round of crowdfunding. Thus, these appearances were not as effective at developing support beyond the first “digital flock.” No connection had yet been made with the diverse public offline; promotion was still hovering around the second quadrant of “thin and symbolic.”

Phase II: Escaping Echo Chambers and Creating Thick and Impactful Changes

vimeo:

Video 3: The Staff Slide for Another Promise, Posted on the Facebook Page

Video 3: The Staff Slide for Another Promise, Posted on the Facebook Page

A breakthrough took place in April 2013 when the filmmakers appeared on one particular podcast show hosted by a hip-hop musician. Most of the audience were young fans of the hip-hop musician and not necessarily socially active or informed. After this appearance, however, the filmmakers received dramatically increasing public attention. It is believed that once the film became connected with a new audience, interest in the film snowballed and news readily spread across varied networks at an increasing rate. Over the next two months, roughly 7,000 more people donated about $1 million in exchange for cinema tickets or DVDs. The effect is evident in the list of donors at the end of the film credits. Donations continued after official production and distribution ended; 8,290 people made contributions as of June 2014.

All of this movement provided the funding needed for the production. More importantly, it succeeded in publicizing the issues that motivated the film’s story and helped form a strong and widespread digital civic network. Yoon made it clear that such dramatic attention — what we see as “thick and impactful change” — did not automatically follow the appearance on the podcast show in and of itself. The show certainly brought the filmmakers the new audience they needed, but the main reason for success was the narrative. Such a controversial topic, which most people did not think could be treated publicly in Korean society, had broad appeal.

After production, the film successfully debuted in October 2013 at the Busan International Film Festival (BIFF) under the title Another Family (this title is a famous slogan in Samsung’s commercials, yet it was altered to Another Promise before distribution to avoid potential legal action). Mainstream media, including television broadcasting as well as news and movie magazines, called attention to the film. It seemed that success, a tangible result of the film’s first substantial transition to “thick and impactful” change, was just around the corner.

Phase III: Unexpected Hindrance, Crowd-distribution, and New Participatory Culture

Another Promise was ranked first for audience anticipation the week before its release. Prior to that, however, major film distributors drastically reduced, without prior notice, the number of theaters screening the film. Yoon felt powerless to respond and was about to give up. Then he saw ordinary people and NGOs that were already well-networked online and offline demanding that commercial film distributors and independent theaters in their own locales run the film. Social media (SNS and Twitter) and the Another Promise webpage became a central arena for this action once again. The crowdfunding system turned into crowd-distribution at that point. Through social media and the film’s webpage, people donated tickets to those who wanted to watch the movie but could not afford the ticket price (such as young students). Information was shared about screenings in their area, and supporting comments were posted about the film. In the fourth week of its release, more theaters began screening the film — a very unusual box-office pattern. In May 2014 — at the height of public attention to Another Promise sparked by such digital activism — Samsung made its first official apology to the workers who suffered through cancer and to their families. This was seven years after Hwang first initiated legal action.

> > Although the film barely broke even financially (500,000 people watched it, short of the original target of 700,000), Yoon did not see the film as a failure, but saw it as confirming the possibility of change and promoting civic solidarity.

From the filmmaker’s perspective, the film was made by a civic network of 10,000 ordinary people, not just by the filmmaking team. Above all, without the Internet dramatically boosting the development of an active civic network, the film would not have come into existence at all. Yoon also stressed that the foundation of the film was in the long-standing offline activism surrounding Hwang (Yun-Mi’s father) and Sharp (a group organized by victims of the chip factories’ toxicity and their families). Another Promise was a tipping point for change, but the film would not have been nearly as successful without these earlier contributions.

The film’s most notable triumph, among many others, was to break the stronghold of self-censorship and fear of Samsung’s influence. Indeed, what Another Promise_’s digital civic network fought against was not Samsung _per se. Rather, it was the fear of Samsung deeply entrenched in people’s minds in Korean society.* Another Promise*was not simply a film — it heralded a new phenomenon of digital activism and participatory culture in Korea, showing how thin and symbolic actions online can transform to a collective civic power that enables real change throughout society.

This case study is based on an interview with Ki-Ho Yoon, a producer of Another Promise, conducted on June 6, 2014, as well as on the second author’s experience with The Filmmaking Co-Op.

References

Colleoni, E., A. Rozza, and A. Arvidsson. 2014. “Echo Chamber or Public Sphere? Predicting Political Orientation and Measuring Political Homophily in Twitter Using Big Data.” Journal of Communication 64 (2): 317–32.

Garrett, R. Kelly. 2009. “Echo chambers online?: Politically motivated selective exposure among Internet news users.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication14: 265–285.

Kahne, Joseph, et al. 2012. “Youth Online Activity and Exposure to Diverse Perspectives.” New Media & Society 14 (3): 492–512.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.