Becoming Civic: Fracking, Air Pollution, and Enviornmental Sensing Technologies

Friday, March 4, 2016

Jennifer Gabrys (Goldsmiths, University of London), Nerea Calvillo, Tom Keene, Helen Pritchard, and Nick Shapiro

Within the broader context of civic media, a number of environmental sensing technologies and practices are emerging that seek to enable citizens to use DIY and low-tech monitoring tools to understand and act upon environmental problems. Such “citizen sensing” projects intend to democratize the collection and use of environmental sensor data in order to facilitate expanded citizen engagement in environmental issues. But how effective are these practices of citizen sensing in not just providing “crowd-sourced” data sets, but also in giving rise to new modes of environmental awareness and practice?

The Citizen Sense project investigates the relationship between technologies and practices of environmental sensing and citizen engagement.

Environmental sensors, which are an increasing part of digital communication infrastructures, are commonly deployed for monitoring within scientific study, as well as urban and industrial applications. Practices of monitoring and sensing environments — or citizen sensing — have migrated to a number of everyday participatory applications, where users of smart phones and networked devices are able to undertake environmental observation and data collection. While environmental citizenship and citizen science are established areas of research, citizen sensing is an environmental practice that has not yet been analyzed in detail — although many claims are made about the capacities of digital monitoring technologies to enhance and enable democratic participation in environmental science and politics.

Through three project areas, the Citizen Sense project examines environmental sensing practices, and tests their capacity for generating new types of civic engagement. The first project area, “Pollution Sensing,” concentrates on citizen- sensing practices that use sensors to detect environmental disturbance, with a particular focus on air pollution. The second project area, “Urban Sensing,” examines urban sustainability or “smart city” projects that implement citizen-sensing practices along with sensor technologies often to realize more efficient or environmentally sound urban processes. The third project area investigates “Wild Sensing,” and focuses on citizen-sensing practices that map and track flora and fauna activity and habitats, as well as engage with organisms as organic sensors of sorts. This brief case study describes Citizen Sense project work from the first project area of “pollution sensing” in relation to monitoring air quality near infrastructure of unconventional natural gas extraction in the form of hydraulic fracturing (or fracking) in northeastern Pennsylvania, USA. We consider both how citizen-sensing practices are already underway in this region, and how to contribute to this process through further participatory and practice-based citizen-sensing initiatives.

Environmental Monitoring and Fracking

Pennsylvania has a long history of oil and gas extraction. The world’s first oil well was drilled there in 1859. Since then, some 350,000 wells have been drilled in the state. Nearly 8,000 of these wells are in operation or under development as sites of fracking-based extraction, which has been underway in its current mode of operation on the Marcellus Shale since 2003. The process of fracking involves using water, sand, and a proprietary mix of chemicals, which are pounded into deep shale formations to release reserves of natural gas. A mesh of pipelines, condensate tanks, frack chemical impoundments and compressor stations assemble into landscapes of natural gas extraction. The round-the-clock activity, including a constant stream of freight-truck traffic and the din of heavy machinery generates considerable concerns about environmental disturbance, particularly in the form of water and air pollution. At every step along the course of this infrastructure, chemicals can leak into the air or be released intentionally as permitted emissions. Monitoring activities undertaken by any number of corporate, governmental or advocacy groups in different ways may struggle to give a clear indication of what is in the air.

In the case of fracking, environmental monitoring may become a source of indeterminate and even contentious data. At the disjuncture of official monitoring data and the experiences of residents living on the shale field, citizens are attempting to engage with environmental monitoring to begin to generate evidence that speaks to their particular experiences. Citizen Sense fieldwork has raised multiple questions about what citizen monitoring practices might sense and be able to sense, and within what larger landscape of environmental monitoring might the findings of pollution monitoring be located, questioned, and differently mobilized.

Civic Technology and Practice-Based Research

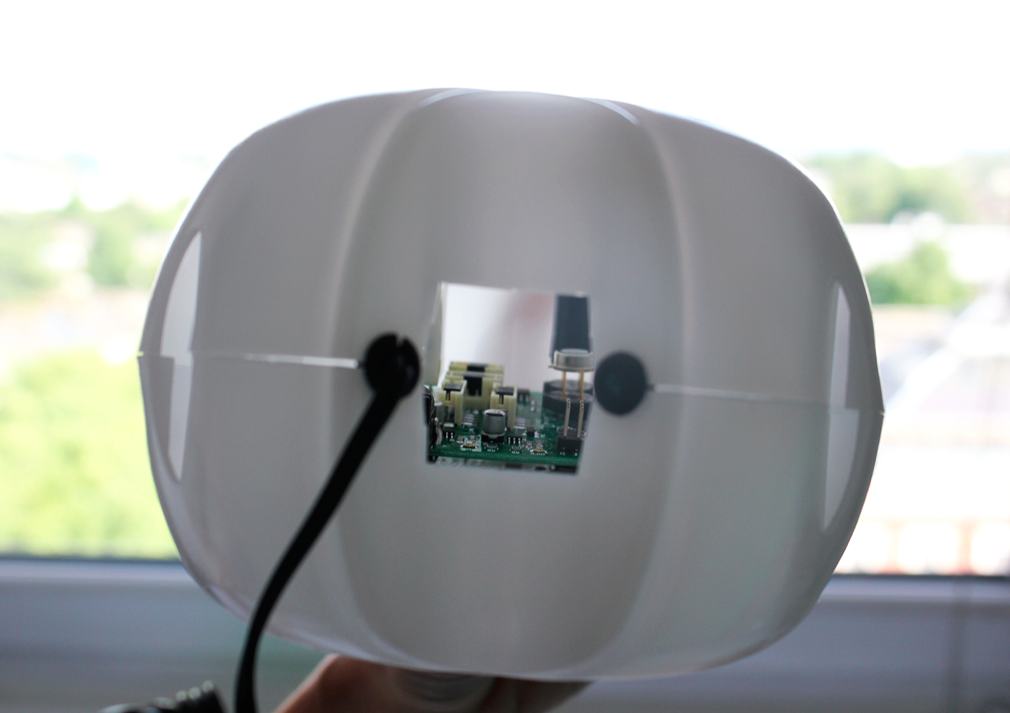

The Citizen Sense project has undertaken both a review of existing citizen-sensing practices attentive to air pollution near fracking sites in northeastern Pennsylvania; and has also collaborated with these communities to identify pollutants and issues of concern in order to develop monitoring kit and events. The methods of the Citizen Sense project are practice-based and participatory, and consist of intensive fieldwork, making and remaking of environmental sensor technologies, site-specific walks to test devices, as well as charettes and workshops to trial and learn about environmental monitoring techniques.

Multiple “kits” have been developed in the course of this practice-based research, from a “Logbook of Monitoring Practices” given to residents that asks them to document their particular concerns and questions about fracking and environmental monitoring; to off-the-shelf digital and analog sensors that capture volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and particular matter (PM); to bespoke digital sensors and web platforms for testing how sensed variables, experience, and collective monitoring data might come together to form new understandings of air pollution. These methods set out to multiply understandings and possibilities of democratized environmental action through citizen sensing practices. In this way, the Citizen Sense project seeks to generate new interpretive understandings of citizen sensing through an iterative relationship between theory, practice and field-based investigations, and to put forward new models for understanding citizen sensing.

Becoming Civic: Environmental Sensing as a Political Technology in Process

The Citizen Sense project is equally invested in troubling how environmental sensors become technologies of action or civic engagement. A common assumption may exist that technologies developed for civic engagement will seamlessly unfold into participatory encounters. Sensors for environmental monitoring are often presented as tools that will facilitate the generation of data on pollution, for instance, which are meant to lead to political engagement and efficacy. Our research has suggested that these are not technologies that are immediately “civic,” however, but that may become civic in specific ways through involvement with communities and concrete environmental problems such as air pollution related to fracking. What are the standards and conditions that lend political effect to sensing practices and data? How does pollution data circulate so as to have effect? How do communities form to convey the importance of monitoring practices and data? These are questions that ask about the civic attachments that may form in relation to technologies, but are not solved by technologies alone.

Many environmental sensor devices, from the Air Quality Egg to AirCasting to Smart Citizen Sensor and more, primarily exist as proof-of-concept technologies, with the sensing capacities of these technologies producing more or less accurate data. Yet the capacities of these technologies in realizing new modes of environmental citizenship often remain untested, even while this is a recurring way in which these technologies are promoted. The Citizen Sense project has set out to put these existing technologies to work in order to understand the social, political and technical problems with which they are entangled; and to test how environmental sensing technologies operate in contexts where more emphasis is placed on the civic and political capacities of these kits in comparison to their technical inventiveness as such.

In other words, the invention of technologies does not automatically lead to the invention of civic engagement. These technologies need to become civic, often in quite different ways depending upon the projects in which they would be put to work. The Citizen Sense project is raising distinct questions about the politics and practices of sense that emerge at the intersection of sensor technologies, citizen participation and environmental change. It is our contention that civic-ness does not automatically follow development of sensors for environmental monitoring. Instead, pollution-sensing technologies are provocations for thinking about how — in this case — environmental monitoring data on air pollution might be collected, communicated and acted upon, and to what effect. Citizen sensing is not just made up of observations of environmental change, but also involves technical and political practices that form a complex ecology of sensing. Environmental sensors and DIY platforms may not offer up a simple pathway from citizen-collected data to effective political action, but they do open up an expansive set of questions about how civic engagement forms attachments in and through particular technologies, how communities might assemble to address distinct environmental problems, and how digital technologies are but one part of this larger effort to invent new modes of environmental and political practice.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007–2013) / ERC Grant Agreement n. 313347, “Citizen Sensing and Environmental Practice: Assessing Participatory Engagements with Environments through Sensor Technologies.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.