Blogging for Truth: Ai Weiwei’s Citizen Inevestigation Project on China’s 2008 Sichuan Eearthquake

Friday, April 8, 2016

Jian Xu (China Research Centre, University of Technology, Sydney)

On the afternoon of May 12, 2008, a 7.9 magnitude earthquake hit Sichuan province in China, killing at least 6,8000 people and leaving over 18,000 missing. The central government and the state media proactively reported the disaster, setting up “a major departure from China’s past tendency to conceal crises” (Tran 2008). However, the proactive and innovative crisis communication didn’t mean that the Chinese government had changed the conventional information control in the times of crisis (Tran 2008). Minefields still existed in the coverage of the Sichuan earthquake, such as the notorious schoolhouse construction scandal.

The earthquake demolished over 7,000 classrooms, and killed thousands of students. The large death toll led to wide discussion about the quality of the school buildings. This, in turn, led to allegations of corruption against government officials and construction contractors, who were complicit in constructing sub-standard school buildings while pocketing the remaining surplus. The scandal soon became a focal point of reporting. Despite initial openness to media’s crisis reporting, the Chinese government issued notice to media outlets ordering them to downplay the issue, and forced China’s most famous liberal press, Southern Metropolis Daily and foreign media to withdraw from the earthquake zone in case they further investigated the scandal (Weaver 2008). When media’s investigative reporting of the scandal was suppressed, some social activists, public intellectuals, and activist bloggers initiated independent investigation projects to further look into the issue. Amongst them, Ai Weiwei’s citizen investigation project was one of the most well-known and influential projects.

As a contemporary artist and intellectual activist with international reputation, Ai Weiwei was unsatisfied with the government’s refusal to release the death toll of the students. He intended to compile a name list of schoolchildren killed in the school buildings by doing independent investigation. In an interview about his investigation, Ai Weiwei argued “all citizens should have the rights to supervise the government, as well as the responsibility to investigate the truth when the government keeps silent” (Wu 2009). The main purpose of the project was to “show respect to every individual victim’s life and refuse to forget the tragedy” (Wu 2009).

On December 15, 2008, Ai Weiwei’s Citizen Investigation Group (CIG) was formally set up in his studio in Beijing. The CIG started collecting profiles of student casualties through limited online information, such as mourning websites and reports from NGOs. In order to obtain complete information, on January 17, 2009, CIG sent 4 volunteers to Sichuan to collect students’ profiles. They visited 21 villages and towns, interviewed the parents of the student victims, and shot scenes of the collapsed schools, obtaining valuable audio-visual materials from the disastrous area. They further sorted out the materials, compiled name lists of student victims in different schools, and sent the lists to the head office in Beijing via email. On March 15, Ai Weiwei released, on his personal blogs, the first investigation report on China’s two major commercial portal sites: Sina and Sohu (Hassid, 2012), based on the information provided by CIG. Tianya Forum — China’s most influential Bulletin Board System (BBS) with nearly 92 million registers — soon reposted the report, which gave rise to heated online discussion about Ai Weiwei’s citizen investigation. The suppressed schoolhouse construction scandal re-entered the public discursive sphere through alternative online communication. Ai Weiwei’s blogs soon became reliable information sources for those who wanted to know the truth of the scandal.

Having attracted great attention from the public, Ai Weiwei began to use blogs to mobilize the public to participate in his project. On March 20, he posted advertisement to recruit volunteers. The ad received considerable feedbacks from the audience; and from March 25 to April 21, three batches of volunteers (18, 9, and 11 people, respectively) were recruited and sent to Sichuan. Ai Weiwei kept blogging with the first-hand information sent from the front-line. From March 21 to May 29, Ai Weiwei had posted 202 blog entries to release the name lists of student victims and 115 entries to document the volunteers’ investigation. The page view of his blogs reached more than 10 million. In addition, his blog entries were widely circulated and reposted on BBS, blogs and instant messaging platforms, such as QQ and MSN, making his investigation a hot Internet event.

Banned by China’s mainstream media as a politically sensitive topic, Ai Weiwei sought attention from overseas media outlets to publicize his investigation result. By May 8, 2009, he had accepted nearly 70 interviews from overseas media, including NBC, BBC, Reuters and NHK, which put the Chinese government under pressure. Under attack both internally (cyberspace) and externally (international societies), the government finally released the death toll of the schoolchildren on May 7, 2009. A total number of 5, 335 students were confirmed dead or missing in the Sichuan earthquake (Ang 2009). However, the names of the lost schoolchildren were not attached with the official figure.

> > Due to the great social influence of Ai Weiwei’s investigation and blogs, the government shut down his blogs on May 29.

Losing the blogging platforms in domestic cyberspace, he moved his blog overseas. He reposted all blog entries on Bullogger.com, a Chinese political website with server based in the US, and continued blogging (All his blog entries about citizen investigation can be found on his personal homepage http://aiweiwei.com). Though the website was also blocked in China, some skillful Chinese netizens, who knew how to circumvent the Great Firewall, could access the site and repost his blog entries in China’s cyberspace, making the reverse flow of the blocked information possible. Millions of netizens reposted Ai Weiwei’s blog entries to support his citizen investigation.

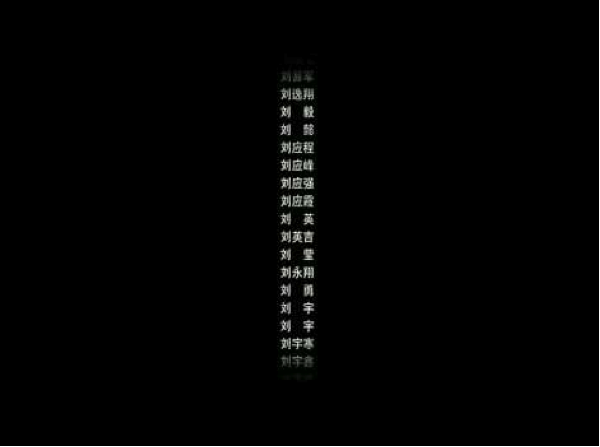

By the end of July 2009, the investigation was largely completed. A total number of 5, 194 students were confirmed missing or dead; the number quite close to the official figure. Moreover, a name list of 4,851 students was compiled and released on his blog. As an artist, Ai Weiwei also used artistic forms to present the findings of his citizen investigation project and to memorize the perished students. In late 2009, he released two audio-visual works: 4851 and Hua Lian Ba Er. 4851 is a long name list of student casualties with background music only. Hua Lian Ba Er is a documentary film, which documents the CIG’s investigation of the schoolhouse scandal.The links of the audio-visual works were widely circulated online, allowing more people to know his investigation in a more visual and direct way.

Ai Weiwei’s citizen investigation project, blogs were the central platforms to release investigation report, interact with audience both online and offline, mobilize public opinion, and build national and transnational advocacy networks. In China, where mainstream media are still tightly controlled, and collective protests offline are very likely to be cracked down in disasters and crises, blogging and microblogging have shown both “symbolic” and “material”(Lievrouw 2011) functions albeit under censorship (Lee 2013). They represent the suppressed agenda as alternative journalistic practice, and also enable the right defense actions of the marginalized groups enacted in a relatively safer mode of interaction and engagement centered on the Internet. In addition, a group of what Kellner calls “new critical intellectuals” (Kellner 1998) is emerging in China’s new media age, such as Ai Weiwei. They could “intervene in the new public spheres produced by broadcasting and computing technologies” and use new technologies to “attack domination and to promote education, democracy and political struggle” (Kellner 1998). The interplays between China’s new critical intellectuals and new media users centered on the new media platforms have fostered new characteristics of China’s civic activism and engagement in the Web 2.0 era.

References

Ang, Audra. 2009. “China — — 5,335 Students Dead, Missing in 2008 Quake.” PostBulletin.Com, May 7.http://www.postbulletin.com/china-students-dead-missing-in-quake/article_128d67c3-9b06-5b7f-a7f5-8ecd83dd42fc.html (accessed June 10, 2014).

CNNIC. 2009. “2008–2009 Zhongguo Boke Shichuang Ji Boke Xingwei Yanjiu Baogao,” (2008–2009 Research Report on the Chinese Blogosphere Market and Behavior), July.https://www.cnnic.net.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/sqbg/201206/P020120612509155387996.pdf (accessed June 4, 2014).

Crube, Katherine. 2009. “Ai Weiwei Challenges China’s Government over Earthquake.” ArtAsia Pacific, Jul/Aug. http://artasiapacific.com/Magazine/64/AiWeiweiChallengesChinasGovernmentOverEarthquake, (accessed June 15, 2014).

Hassid, Jonathan. 2012. “Safety Valve or Pressure Cooker? Blogs in Chinese Political Life.” Journal of Communication 62(2): 212–230.

Jacobs, Andrew. 2008. “Parents’ Grief Turns to Rage at Chinese Officials.” The New York Times, May 28. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/28/world/asia/28quake.html (accessed May 30, 2014).

Kellner, Douglas. 1998. “Intellectuals and New Technologies.” Cryptome.org, January 23.http://cryptome.org/jya/kellner.htm, (accessed June 10, 2014).

Lee, Jyh-An. 2013. “Regulating Blogging and Microblogging in China.” Oregon Law Review 91 (2): 609–620.

Lievrouw, Leah A. 2011. Alternative and Activist New Media. Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press.

Tran, Tini. 2008. “Media Given Green Light to Report on Disaster.” Toronto Star, May 15.http://www.thestar.com/news/world/2008/05/15/media_given_green_light_to_report_on_disaster.html, (accessed May 24, 2014).

Weaver, Matthew. 2008. “Police Break up Protest by Parents of China Earthquake Victims.” The Guardian, June 3. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/jun/03/chinaearthquake.china?gusrc=rss&feed=networkfront, (accessed May 30, 2014).

Wu, Aiyao. 2009. “Wechian Dizhen Zhihou, Shui Sizai Dierci.” (After the Sichuan Earthquake, Who Will Die in the Second Time?) Nanfeng Chuang (South Reviews), April 22.http://www.nfcmag.com/magazine/81.html (accessed May 28, 2014).

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.