Crowdfunding Civic Aaction: Pimp My Carroça

Thursday, March 3, 2016

Rodrigo Davies (Center for Civic Media, MIT)

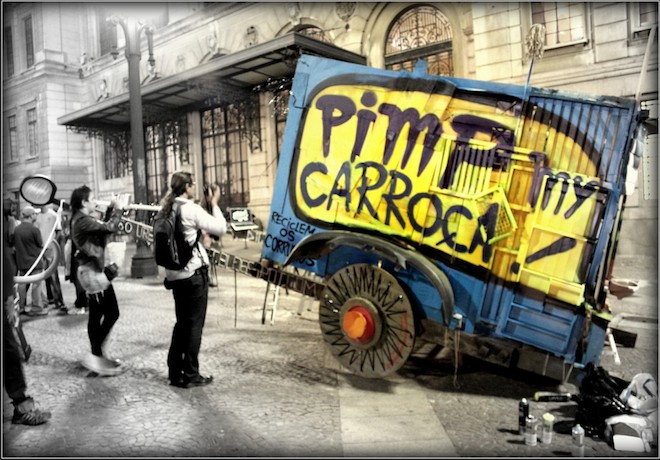

Crowdfunding, the raising of money from large numbers of small donors using online platforms such as Kickstarter and IndieGoGo, has emerged as a very popular means of supporting a wide range of projects in the past five years: from film and music releases, to consumer technology products and scientific experiments. The practice is also beginning to be applied to projects that provide services to communities, such as public parks, community centers and grass-roots civic action (Davies 2015). Brazil offers one of the best examples of how civic crowdfunding can be used as a powerful movement building mechanism: Pimp My Carroça (Pimp My Wagon) was a public art campaign to highlight the condition of waste pickers in Sao Paulo, and to advocate for worker protections. It leveraged the emergent practice of civic crowdfunding both to gather financial resources and build a popular movement around its civic goals.

Sao Paulo, a city of more than 11 million people, recycles less than 1% of its 17,000 tons of daily waste. Ninety percent of the recycling activity that occurs is carried out by waste pickers, or catadores (Offenhuber 2012; Parede Viva 2012). Despite the contribution they make to the city, however, the catadores are either ignored by the rest of the city, or face complaints and abuse from drivers and police officers, who blame them for blocking traffic. Angered by the treatment of the catadores, Mundano, a 27-year-old artist from the city, decided to intervene on their behalf (Davies 2014). In 2007 he began befriending waste pickers and offering to paint their carts, as a way of making them more visible to traffic around and giving each person he worked with an individual identity. He painted 160 carts over five years, in cities around Brazil (Mundano 2012b). The murals often contained political messages, such as “One catadore does more than an environmental minister” and “Se eu pudesse eu reciclava os politicos” (If I could I would recycle the politicians), although his primary goal was to increase public awareness of the catadores and their contribution to the sustainability of Brazilian cities (Parede Viva 2012). More often, he painted messages such as ``Eu carro não pollu’’ (My car does not pollute) and “Eu reciclo, e você?” (I recycle, what about you?) (V2 2009).

> > “These people… support their families through a living based on our waste. They work in the middle of the city, silently. They do work for everybody and nobody notices them. Or if they do, they say, ‘there’s a homeless person.’ It’s totally wrong… They’re employed people, working honestly. I painted carts… to make people think about this problem. This is my life’s mission.” (Mundano 2012b)

But his one-man mission needed greater scale in order to have a larger impact, so in early 2012 Mundano created a crowdfunding campaign on the Sao Paulo-based platform Catarse in order to grow the movement. Mundano and the three other local graffiti artists with whom he runs Parede Viva (Living Wall), a graffiti collective and education program, named the campaign Pimp My Carroça (Pimp My Wagon, or PMC), echoing the MTV series “Pimp My Ride,” in which contestants’ cars are refitted and redecorated by professionals. The group’s goal was to raise BRL 38,200 ($17,260) to fund supplies to paint 20 waste pickers’ carts at a public event. The catadores would also be given free medical consultations from local doctors. They also planned to make a documentary film about the movement and the public art event (Mundano 2012a). They offered backers credits in the documentary, vinyl stickers, t-shirts, recycled bottles and artwork.

Contagious Success

The PMC campaign opened on March 27, 2012, and during its first five days rose almost a quarter (22%) of its target. By the end of April the campaign had raised just over half of the total, and the median donation was between BRL 20 and 30 throughout this period. On May 3 the campaign received by far its biggest donation up to that point, of BRL 3,000, from a backer in Rio de Janeiro. It was the third-largest pledge the project received overall. A week later, two days before the deadline of May 11, the campaign met its target after the 704th backer pledged BRL 100. The success of the campaign was contagious. In the three days after hitting the funding target, PMC raised BRL 25,669, more than it had risen in March and April combined (One backer was recorded on May 14 due to a delay in payment processing). While the three largest backers, two of which participated in the final three days of the campaign, accounted for almost a third of the overall raise, most donations were clustered around BRL 30.

The large volume of relatively small donations suggests that the PMC outreach strategy, which focused on email, in-person communication and social media accounts of the members of Parede Vida (PV), was very successful. Mundano tweeted 93 times about the campaign on his Twitter handle mundano_sp, receiving mentions and retweets from Brazilian celebrities with large Twitter followings, such as Sergio Marone (399,000) and film director and television host Marcelo Tas (5,000,000) (Social media analystics service Topsy). The campaign’s reach was also highly localized: four out of five backers (631) listed their address as being in Sao Paulo. Nevertheless, the project did receive nationwide attention and attracted backers from 17 of Brazil’s 27 states. The PMC campaign was a great success in terms of surpassing its goal and achieving broad-based, small-dollar support for a civic issue. It’s notable that close to half of the campaign’s 792 backers, 346 were first-time users of the Catarse platform (The data used to analyze pledging amounts and behavior was anonymized).

On June 5th, over 1,000 supporters of the campaign gathered in Sao Paulo for the “pit-stop” event, at which Mundano and the PV team painted the carts of 50 waste pickers. Following the event, waste pickers and their supporters marched to the center of Sao Paulo for a rally at which they presented a manifesto calling for labor protections for waste pickers (Parede Viva 2012). The group was invited to participate in several events and exhibitions across Brazil, and as planned, made a short documentary film, which was released and circulated online.

To Curitiba and Beyond

In September 2013 PV opened a second PMC crowdfunding campaign on Catarse, for catadores in Curitiba. It raised BRL 44,888, 117% of its target, from 502 donors. Backers for the campaign were split between Curitiba’s state, Parana, and Sao Paulo, which contributed two-fifths of the backers. The Curitiba “pit stop” event attracted 29 catadores and their families, 150 volunteers and doctors.

PMC Sao Paulo and its Curitiba spinoff are effective examples of tactical civic, urban interventions that can attract broad-based support from crowdfunders. PV has been able to grow and retain its digital community since the first campaign, and has 10,000 followers on Facebook, even though the group had not used the platform before the end of the Sao Paulo campaign. Although the campaign did not elicit a public response from policymakers, this was not the campaign’s primary intended output. Mundano and PV are happy to make rhetorical challenges to the political establishment, but their theory of change is rooted in public engagement and education, changing the discourse around waste pickers. In this respect the campaign was successful in using crowdfunding to support the building of a movement around sustainability issues. PV continues to use the PMC Sao Paulo Catarse page as a place to engage supporters and has posted eight updates to January 2014, including news from Sao Paulo and Curitiba. Their latest update suggests that they are considering crowdfunding events for catadores in other Brazilian cities in the coming years.

“We once again appreciate your involvement… continue watching our movement, which only continues to grow and has no ambition of stopping anytime soon” (Translated, Parede Viva 2012, Original text: “Agradecemos o envolvimento… continuar acompanhando o nosso movimento, que felizmente só cresce e não tem ambições de parar tão cedo!’’).

References

Davies, Rodrigo. 2015. “Four Civic Roles for Crowdfunding.” In Crowdfunding the Future: Media Industries, Ethics and Digital Society. London: Peter Lang. Under Review.

Mundano. 2012a. “Custos — Pimp My Carroca 2012.” https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0Ao8hmRpvVO_PdGdwZGlWVmVBZmR0Sm9OTVo4WjJDc0E#gid=0.

— — — . 2012b. “Mundano: Pimp My Carroca: A Street Artist Celebrates Trash Collectors.”TEDTalentSearch. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X0AydRnNnlM.

Offenhuber, Dietmar. 2012. “Tracking Trash with Waste Pickers in Brazil, MIT CoLab Radio. Http://colabradio.mit.edu/tracking-Trash-with-Waste-Pickers-in-Brazil/.” http://colabradio.mit.edu/tracking-trash-with-waste-pickers-in-brazil/.

Parede Viva. 2012. “PIMP MY CARROCA, Catarse.” Catarse. http://catarse.me/en/pimpmycarroca.

V2, Paulo. 2009. “Graffiti Brazil: Mundano.” Abduzeedo. http://abduzeedo.com/street-art-mundano.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.