DIY Citizenship in the New Northern Ireland: The Case of a Belfast Makerspace

Wednesday, March 30, 2016

Dr. Pip Shea (Ulster University)

Introduction

Northern Ireland is emerging from a violent sectarian conflict colloquially known as The Troubles. Contested top-down peace building initiatives (Murtagh 2011, 1132) imposing socio-economic development agendas on local actors underpin approaches to change (Richmond and Mitchell 2011, 338). The following case offers an alternative perspective of the “new Northern Ireland” (Ramsey 2012, 165), the story of Belfast’s Farset Labs[figure 1]. Branded a makerspace, Farset Labs offers new paradigms of civic participation inspired by a culture of contribution, social learning, and technology experimentation. Farset provides a platform for the assembling of self-directed civic identities, or so called, do-it-yourself (DIY) citizenship (Hartley 1999, 5). The organization offers evidence of emergent, multi-faceted civic participation linked to a global movement encouraging DIY ethics through making (Gauntlett 2011, 11).

Background: why this case?

Recognized as a non-profit with charitable status and affectionately known as a “geek gym,” Farset Labs relies on monthly membership fees to operate. Situated near Belfast’s City Centre, Farset offers members and the local community a space to make and modify hardware and software. The organization’s online and offline operations are mutually inclusive. Its geographical position and digital networks work in tandem to influence its member base and outreach activities. Farset’s landlord is a key patron, offering the organization flexible rental terms and the freedom to “hack the space” to make it more appropriate for their operations. The lab also offers resources and activities traditionally associated with community centers such as informal education programs and free social events. Tinkering and experimentation activities situate the organization, however Farset Labs’ director Andrew Bolster — one of four (Ben Bland, David Kane and Dylan Wylie)— admits the venture “has only got a little bit to do with technology,” citing the facilitation of social connection as its most important function (“Nesta in Belfast” 2014). The byproduct of this is strong ties between Belfast’s technologist and maker communities that lead to new modes of civic participation.

Presentation of findings

Farset Labs offers fertile ground for self-directed civic activities. Traditional community organizing tactics such as “Town Hall” meetings invite members to actively govern the space. Town Hall participants discuss events, facilities, finances, marketing and communications, and are invited to contribute to meeting agendas in shared online documents.

The online forum Farset Discourse (“Farset Discourse” 2014) offers a collaborative platform for knowledge sharing that supports lively discussions about events, projects, and the operations of the space.In mid-2013, the successful crowdfunding of a 3D printer offered another example of civic participation, as people became involved in directly financing equipment for the space.

> > Community outreach is a key civic activity of Farset Labs.

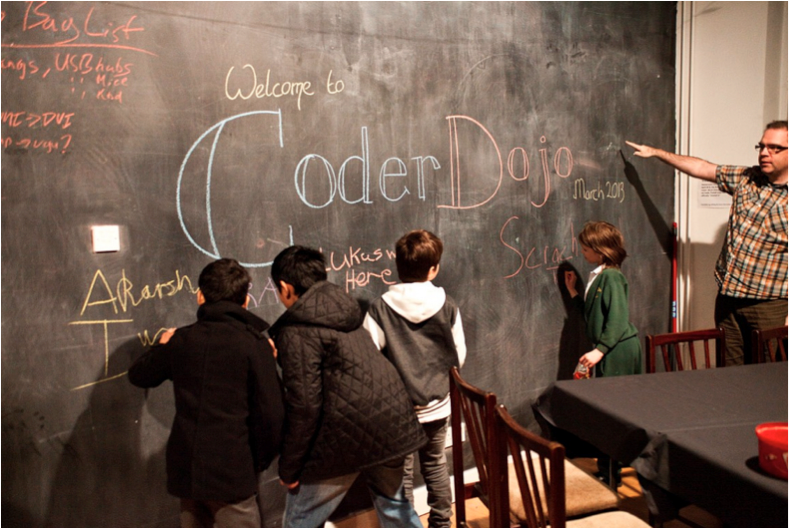

CoderDojos offer free coding clubs for young people [figure 2]: Farset Lab members volunteer as mentors to help participants design games, create websites, and build robots. Other volunteer-run community engagement activities include Raspberry Jams, which are informal education workshops that explore the basics of the Raspberry Pi single board computer. Free Flacknites (Farset Labs Hack Nights) are another event offering (“Farset Labs Decimated” 2014). Flacknite participants are challenged to finish a technical project or solve a problem in twenty-four hours. The organization has also established links with the local business community: Intel signed up as a corporate member and made contributions in the form of hardware donations.

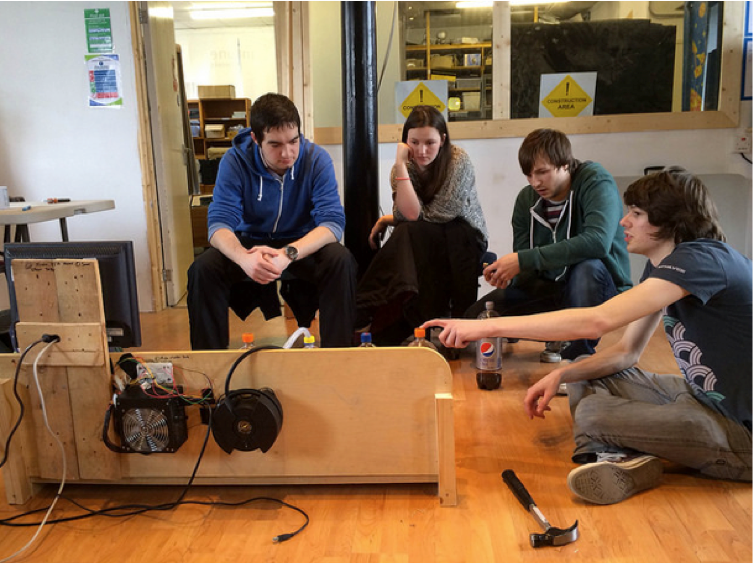

Underpinning this civic participation are critical making activities, where the modification of things inherently challenges existing systems of authority (Ratto and Boler 2014, 5). Farset’s encouragement of the reuse of technology “waste” is one such example. At a recent hackathon, the winning team was singled out because they used toilet cisterns to make a Twitter-powered drinks dispenser [figure 3]. Critical making is also apparent in the organization’s use of an Extendible Hardware Donation License (“Extendable Hardware” 2014), a sharing paradigm that gives equipment owners of the flexibility to donate their hardware under conditional arrangements.

Conclusion

Makerspaces are an emergent institutional form facilitating new civic media rituals. The socio-technical dynamics of these civic activities are site specific and nuanced, as members engaged in DIY citizenship generate new modes of civic participation. In the case of Farset Labs, the foundation of these new civic identities is a culture of sharing and learning that extends from hacking microcontrollers to collectively developing the social contract for membership. Although different demographics use Farset Labs as a platform for DIY citizenship, barriers to participation still exist. More formal institutions are often accountable to diversity policies, but grassroots cultural infrastructure like Farset Labs primarily rely on the participation of people who have agency. The collectively determined aims of the organization also have the potential to limit the performance of civic identities.

Farset Labs are a node in a system that has been described in humanities research as connected learning, the foci of which are social learning and the making (Ito et al, 75) of things that happen across different sites and locations, online and offline. The activities facilitated by Farset Labs extends the social learning of making by encouraging alternative thinking and responsible action, which challenges normative understandings of democratic systems and civic participation.

References

Hartley, John. 1999. Uses of Television. London: Routledge

Ito, Mizuko, Kris Gutiérrez, Sonia Livingstone, Bill Penuel, Jean Rhodes, Katie Salen, Juliet Schor, Julian Sefton-Green and S. Craig Watkins. 2013. Connected Learning: An Agenda for Research and Design. Irvine: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Murtagh, Brendan. 2011. Desegregation and Place Structuring in the New Belfast. Urban Studies 48 (6):1119–1135.

Ramsey, Phil. 2012. “A Pleasingly Blank Canvas”: Urban Regeneration in Northern Ireland and the Case of Titanic Quarter. Space and Polity 17 (2):164–179.

Ratto, Matt, and Megan Boler. 2014. Introduction. In DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media, Eds. Matt Ratto and Megan Boler. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Richmond, Oliver P., and Audra Mitchell. 2011. Peacebuilding and Critical Forms of Agency: From Resistance to Subsistence. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 36 (4):326–344.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.