Emerson Engagement Lab’s Indie Game Discussion Group Post Mortem

Friday, December 4, 2015

By Jordan Pailthorpe

05/18/2015

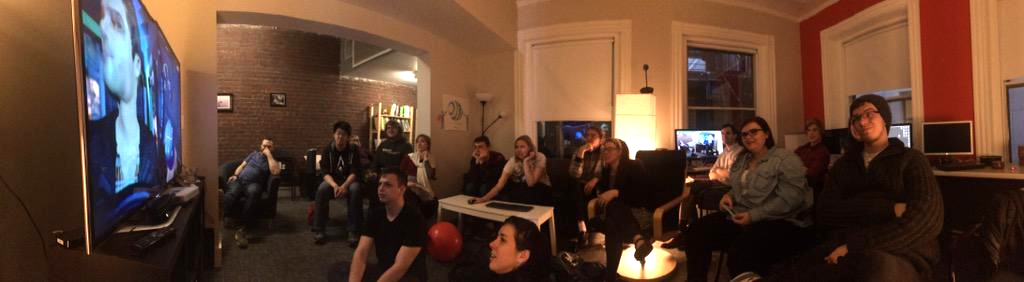

Over the last five weeks of the semester, I started something I call the Indie Game Discussion Group. Every Thursday night at the Engagement Lab 10+ students, faculty, and local game enthusiasts would gather in our common space to play and discuss alternative games in a semi-formal setting.

Each week we would play a new indie/art game or collection of games and discuss theme, design (technical and artistic), and rhetoric. Through contemporary and relevant game studies readings that were specifically aligned with the games being played, we explored the games in context of the discourse in which they were created. The games we discussed in this event series typically fly under the normal “gamer” radar and push the boundaries of what digital games are and can be.

I had two main goals in mind when starting this group:

Generate a community at Emerson that participates in an ongoing critical engagement with the contemporary indie game discourse.

Provide an outlet for Emerson students who are interested not just in playing games together, but talking about games together, in an environment that bridges the gap between a formal class and a free form club.

There are many meetups and workshops that help connect designers to audiences or designers to other designers, but there are hardly any local groups at Emerson and in the wider Boston community that explores surrounding culture from a critical distance . Ultimately I wanted there to be a place at Emerson for students, faculty, and local game creators/critics/designers to meet in an informal setting to play, talk, and critically engage one another.

When starting this group, I had no idea if it was going to sustain itself or even do something interesting. After five weeks of a “trial run” in preparation for a full launch next fall, I feel as though the group was as successful as I had hoped and even exceeded some of my early expectations.

The Structure

At the start of each week I would create a list of games that center around a specific genre, theme, or idea. Each session would place students into a different kind of play experience, either asking them to play games together in small groups, take turns switching off hot seat style while others observed/directed, or even watching lets play videos where we would watch an online personality play through a game for us. For example, in week 4’s discussion “The rebirth of ASCII and how mystery can make games go viral “ we discussed and played incremental games such as Candybox and Drowning. Because these are somewhat passive games that require a player to leave them running and return to them at certain moments during the day, we loaded all the games immediately at the start of the session with one persona guiding the mouse, but taking direction from the entire group.

In addition to the games, I would also pair each collection with an essay from a prominent or important voice in games writing. For week 4 we read Leigh Alexander’s Essay “Why Candy Box became more social than ‘social games’” which framed our thought process and directed us towards particular questions while playing. This piece was very important to me and I think helped the participants see that this kind of discussion does not happen in a vacuum.

This also worked towards exposing them to important voices in games, likeLeigh Alexander or Austin Walker or Kent Sheely whose work informs and articulates this critical investigation.

Therefore we were not just playing games and talking about them, but framing the discussion by pairing games with a particular theme and supporting that theme with a recent essay by a prominent voice in game criticism.

What worked?

Starting from a base set of interested participants

Instead of trying to organize this, picking a time to hold it, and advertising, I tried to engage with the students I knew were already interested in this kind of work. Many of these students came from past classes who displayed interest in game design/criticism or other teacher’s recommendations. In addition, almost 75% of students who attended every week were first and second year students. To find a time that worked best I sent out a doodle survey to gauge which days and times worked best for them and then picked the day with the most availability.

The free-form, drop in/drop out nature of the group.

I feel we benefited from having isolated discussions that started and concluded each night, rather than having ongoing gameplay sessions over the course of a couple weeks. This helped bring in new students and didn’t make them feel like they missed something or weren’t prepared to engage. Every week had at least one new person, either a friend of a regular participant or someone who heard about the group in passing or by word of mouth. This type of “drop in/drop out” form helped establish the group as a safe space that doesn’t penalize or shame those who aren’t at every session.

The weekly, structured meeting time doesn’t shift or change.

Perhaps this is a slightly obvious point, but one I think it’s worth mentioning. A group like this thrives on having consistency to establish importance. It was crucial to have a meeting every week no matter what and to keep them at the same day/time. Otherwise students might not have known it was happening and might not have shown up or even bothered to find out.

Attention to accessibility, representation, and game literacy.

Within the core group of students who came to all the meetings, there was a wide range of experience levels with gameplay and game thinking. It was important to keep an eye out for those who identified as “not a gamer” and took that vulnerable risk of coming into a space consisting of what they most likely felt were experts (though no one in the group self identifies that way). I made sure to invite those who wouldn’t readily volunteer to play and gave them the chance to take the stage. I especially was aware of doing this whenever noticing a student slipping away from the conversation, intentionally or subconsciously. This sense of inclusion really helped to gel the group together and I think helped retention as well.

Structured, moderated discussion.

Instead of just having students speak on how they were feeling, we settled into a moderator/teacher-student structure fairly quickly. Most of the time the night would start with me posing a question and students raising their hand to enter the queue to answer, pose a new question, or comment on what they were seeing. Soon enough they were responding directly to one another without dominating the conversation or regressing into isolation. It sounds strange to have students raise their hand to speak in order of turn within an informal setting, but this allowed for all voices to be heard. Establishing this rhythm early on solidified the structure of each discussion and gave folks who were shy an opportunity to speak.

Choosing games not many have played to expose participants to new ideas.

Everyone loves to talk about the things they like or know well. The first week I asked everyone what they would want to see played in this group and quickly realized if I catered to everyone’s wishes the discussion would regress into already solidified opinion versus solidified opinion. Though I do want to work towards student curation and explore more popular games critically (more on that below!), I feel it was beneficial to not use games many were familiar with and instead highlight those games and people that no one ever knew about. Basically, if it had a TV commercial or you could buy it in Gamestop we probably weren’t going to play it!

What didn’t work?

Playing one game for the night as opposed to multiple shorter game experiences

The first week we played Lucas Pope‘s *Papers, Please* which is an amazing game that I teach every semester in my game design research writing class at Emerson. Though it is such a great game that can be played and rhetorically understood in a few hours, it was just a tad too long for our group. I found that having a handful of smaller game experiences, some that could be completed in under 90 seconds , helped break up the night.

Letting the conversation delve into “it’s not a game because x reason”

Though I think its an important question to ask and interrogate, the “this is not a game” argument is loaded with political ramifications that typically devolve into problematic territory. We talked about why a game would do what it does and the reasons a creator would, in Robert Yang’s example, lock out players from future playthroughs due to actions the player makes in-game, but anytime the conversation became negative without valid critical inquiry it would come to a screeching halt. I think I could have avoided this with better leading questions or some kind of on-boarding for why this is a hard question to ask/investigate.

What do students have to say?

For the question of the night on the last week I asked each student what they liked about this experience and why they kept coming back. I’ll let their quotes speak for themselves:

There are just so many games out there, but I didn’t even know half the games we played and it opened my eyes to what you can really do with games if you aren’t constricting yourself to what you would “think” to play. There is an unexplored passion for videogames at Emerson that we could do more with.

I just like being able to talk about games without being graded on it. And the themes! The topic section is really great! I like that anyone can show up and that it is inclusive.

Games are really smart yet before this group I definitely didn’t know how many applications there are for them. I like listening to everyone speak eloquently and critically about games.

I like how this group strikes a great balance between being informal and having a definite structure. I like watching other people play games. It helps give a new perspective on their design.

I like being able to think critically about games and have critical discussions about them. Before this group I only thought about how enjoyable games are. This has opened my eyes to a different way of thinking about them.

I like seeing how much diversity there is within game design, how many games are being made and how many niche concepts that I would never even imagine could exist. Its inspiring to see so many people do so many things.

The future and plans for next fall

As much as I enjoy curating the games and providing a baseline for the discussion, my ultimate goal with this trial run was to build a base of engaged students who would want to curate and lead the discussion each week, replacing me as a focal point for the group and giving control to them.

Ultimately, I hope this will show Emerson how much of a thirst there is for the study of games within the college. At the moment, there is only a few game focused classes that are solely interested in design and skill development. There is not one theory based class on games, not one class on the critical inquiry into the discourse of games.

For the past four semesters I have been teaching a research writing course as a game design and study course. This is my attempt at filling this gap and exposing students who might not think there is much to the study or design of games. But with departmental limits and aligning content with strict course objectives, the course becomes limited in how much we can really dive into games as cultural objects worthy of study.

Games are progressively becoming more and more embedded into our daily realities. The study of games and play is just as important as writing, literature, and film-making, and if we don’t prepare creatives with the baseline of this mode we so a disservice to our students and our community.

Therefore, I hope this group makes some noise and shows the college that students want to take games seriously, as designers, as critics, and as writers. If not in the classroom, then in front of our TV screen at 6pm on Thursday nights. If not for class credit, then sole for intellectual curiosity. If not within the ivory walls, than outside them.