FORT VANCOUVER MOBILE PROJECT

Thursday, March 24, 2016

Brett Oppegaard (University of Hawaii)

For more than 100 years, the National Park Service has been integrating new technologies into site-interpretation strategies. Those efforts have evolved and transformed from basic campfire lectures and artifact collections to paper brochures and wayside signs and, gradually, into audio tours and complementary social media sites (Mackintosh 1986; Bacher et al. 2011). The federal agency — the primary caretaker of more than 400 cherished places in the United States — acknowledged in a 2010 report that it now relies primarily on mediated forms of communication to share its messages, rather than ranger lectures and other modes of person-to-person interaction (Bacher et al. 2011). Follow-up analysis, though, also found that the pace of technological innovation throughout the agency had fallen behind the expectations of the general public. Unfulfilled potential remained for advancing historical research, improving interpretation, and increasing engagement with the public through new technologies (Whisnant et al. 2012). Our research team suspected that mobile media could help with this situation.

So the agency created a partnership in 2009 with our team of scholarly researchers (from Washington State University, Texas Tech University, Portland State University, and University of Hawaii) as well as engaged practitioners and community volunteers in the Pacific Northwest. Together, we became focused upon the interpretation of the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. For the past five years, the research team has been exploring interactive and interpretive interfaces at the site. Various grant-funded experiments were designed with mobile technologies to increase community engagement. Highlights of these award-winning efforts are reported here, but more details also are available via a behind-the-scenes blog of the project at www.fortvancouvermobile.net.

In brief, the Fort Vancouver Mobile project has been guided by an action research framework and related methodologies that gather both qualitative and quantitative data through cycles of planning, action, observation and self-reflection. The techniques for this type of inquiry generally have been practical, cyclical, and problem-solving by nature, with the intention of generating change and improvement at a local level but also creating insights applicable to more global situations (Taylor, Wilkie and Baser 2006). Engagement can be approached and operationalized in many ways, but we chose to build upon Mersey, Malthouse and Calder’s (2010) definition of the term — as the collective experiences that people have with a media brand. The project worked with the National Park Service brand to focus upon these particular factors, related to interactivity: involvement (O’Brien and Toms 2008; O’Brien and Toms 2010), satisfaction (Patwardhan, Yang and Patwardhan 2011), and social facilitation (Mersey, Malthouse and Calder 2010).

Those experiments and studies generally have been exploring research questions about the following:

• The medium — Examining the mobile medium’s distinct relationships to media objects, audiences, authors, and society. One of the first experiments at Fort Vancouver was to observe the current media use and then compare that to interventions with other mediums. This process included watching site visitors explore The Village area, a remote historical location at the site, without any adjustments by researchers. That experience included access to two wayside signs and external-only viewing of two small, reconstructed houses. During the second phase of the experiment, the visitors also were given a standard brochure about The Village. In the third phase, they were given a prototype mobile app, and in the fourth phase, they were given an even more refined prototype of a mobile app, to observe how the experiences changed with the different mediums in place.

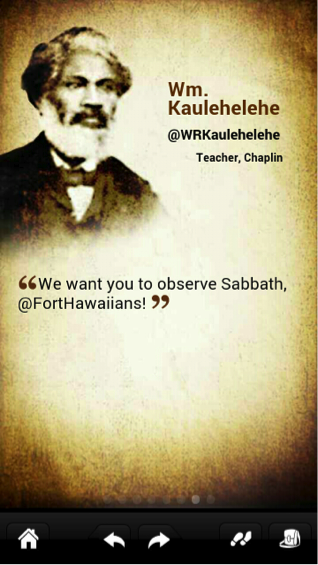

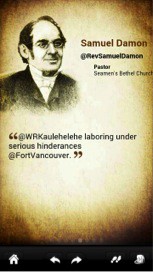

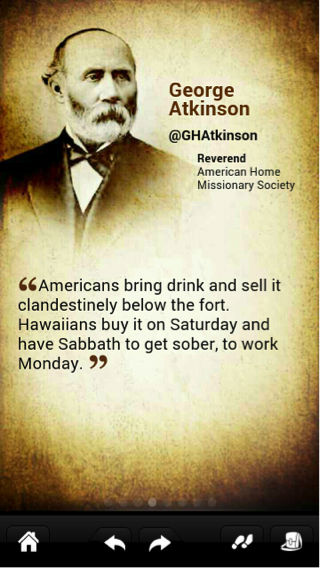

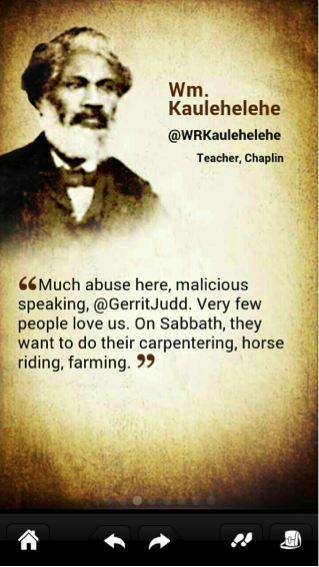

Example: A Tweet-alogue –

We had mountains of material — historic letters, diary entries, and book sections — about the real-life characters in our “Kanaka” narrative. That included back-and-forth exchanges between the story’s protagonist, William Kaulehelehe, a Hawaiian-born chaplain brought to Fort Vancouver to proselytize to fellow Sandwich Islanders, and the administrative and social leaders of the region. But much of that compelling discourse was buried in the minutiae of dense and dry procedural accounts from the era. To make the dialogue more accessible, and engaging, we took excerpts and added a touch of Twitterese, such as @ signs, and then put the pieces back together to form roughly comprehensible conversations. These strings of direct quotes, geolocated and embedded in locations that relate to the topics mentioned, can be animated together by users through a swiping motion.

Media forms

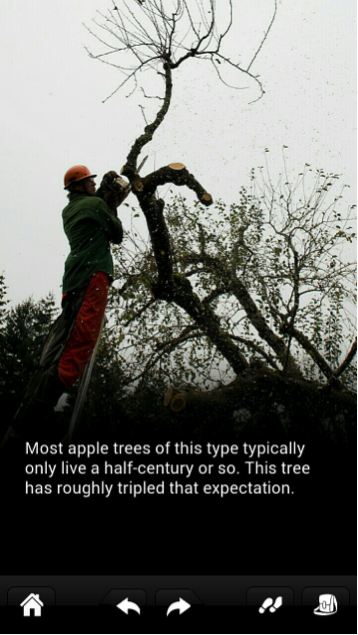

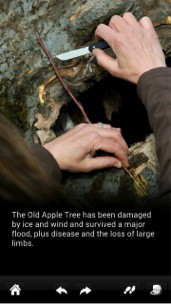

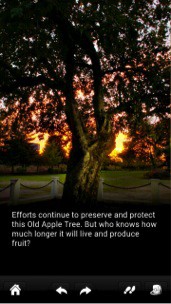

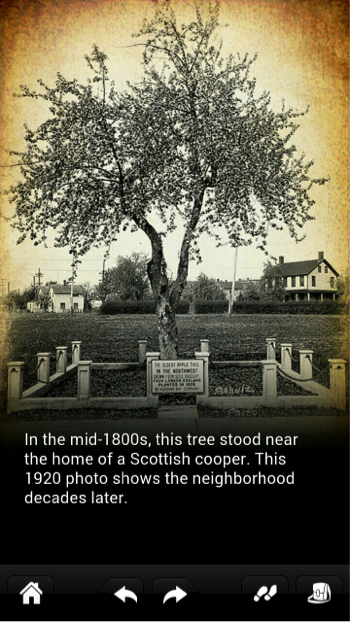

Comparing the effectiveness and efficiency of different media types (audio, video, text, animation) in various situations. The mobile device as a medium brings together in one delivery system most other media forms, such as audio, video, and text. One of the recurring experiments we conducted at the site was in-situ comparisons of roughly equivalent content in multiple media forms. That has included tests, for example, of audio content versus video content at the site of the oldest apple tree in Washington state. In these tests, either an audio or video clip first was randomly pushed to visitors at the site, via tablet computers handed out by research assistants. After hearing or viewing the clip, about the history of the tree, the visitor then was given a short survey about the experience.

Example: Audio versus Video Comparison Old Apple Tree comparable 1 (no sound, with captions):

Old Apple Tree comparable 2 (sound and captions):

Old Apple Tree comparable 3 (sound, no captions):

Old Apple Tree comparable 4 (sound only, no video):

Mobile technologies allow, for the first time, easy access to video interpretations, such as historic reenactments, in virtually any field location. That could include sharing material at the epicenter of some of the nation’s most sacred spaces. While erecting a large movie screen in the middle of the Gettysburg battlefield would be disrupting, to say the least, embedding a video for play on a mobile device in that same spot could be an extremely effective form of interpretation. In our Fort Vancouver Mobile research studies, for example, we have placed various media forms relaying the history of the Old Apple Tree, the matriarch of Washington state’s apple industry, at the base of the tree, so any passersby can access the material. In doing so, we began to wonder what media form would be ideal for such novel interpretation: audio with no visuals, video with captions only, video with sound and captions, or video with sound and no captions. The examples here show how we have tried to make comparable artifacts, with similar amounts of content for knowledge transfer, out of the different media forms.

Interaction design

Studying mobile interaction activities, through audio / video production, discussion prompts, quizzes, physical tasks, etc. One of the overarching goals of the research team is to provide mobile media that prompts other mobile media. So when a video clip, for example, is given to a visitor at a particular site, the mobile app also asks for the user to thoughtfully participate in the history-building of the place, by making something in response to the original clip and to a specific thematic goal. Then, that user-generated content can be shared with other app users. For example, when the Fort Vancouver Mobile app shows a video clip of an archaeologist making an exciting find on location, the app simply asks, before revealing the answer, “What do you think he found?”

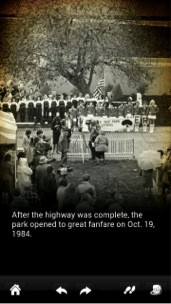

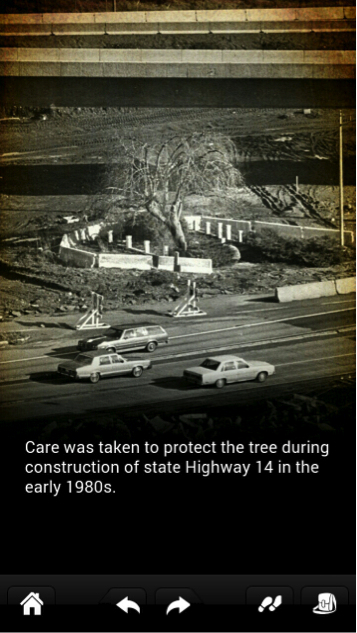

*Example: Embedded Photographs *Similar to the mobile options now available for video, still photography also has emerging potential as an interactive, geolocated media form. In the Old Apple Tree case, mentioned above, we wondered what we could do with still photography that would somehow compel users to participate in the history-making process. With that goal, we bought the rights to a few of the local newspaper’s best images of the historic tree from the past century, added contextual text to those, and through GPS coordinates placed them at the base of the tree, so the Fort Vancouver Mobile app user would be able to compare the tree today with images of it from yesteryear. At the end of this sequence, cycled through via swiping, we asked users if they wanted to pose with the tree and take their own picture. This function turned the mobile camera on, and, when completed, allowed the user to share that image via social media channels. Many of the app users have chosen to take a picture with the tree, and these images have become a part of the fabric of the Old Apple Tree’s legacy.

Remediation

Experimentation with mobile-native compositional styles, including video reenactments embedded at the site of the historic event. Are there new media models that only can, and should, exist in a mobile format? We thought so, and tried to build some of them, including editing a conversation that spanned many historical letters and journal entries among numerous people into a Twitter-like series of exchanges among characters.

Example: Kaulehelehe Video

When creating mobile media artifacts, we often wondered what kinds of new compositional styles could be afforded by the technologies. One of those experiments was this short video. We needed something in our interactive narrative that introduced our “Kanaka” protagonist, William Kaulehelehe, establishing his arrival at Fort Vancouver but also foreshadowing his troubles ahead. Traditionally, videos like these at historic sites are either lectures from rangers or Ken Burns-styled montages. Instead, we decided to tailor the video to the place where it will be watched, in the field, in front of one of the small reconstructed Village houses, and we chose to shoot it at that same location. We also designed the piece to be most comprehensible within the flow of the story, at the juxtaposition of the physical and the digital, meaning it needed the context of the place and the supporting narrative material to make the most sense. In those ways, this is a mobile-native work. It also connects the nearby Columbia River with the interpretation site. It offers subtle historical information, such as the way a gentleman of the era would be transferred from boat to land. It foreshadows the conflicting cultures of the place, as the native Hawaiian chant, about a new day dawning, transitions at the house doorway into a Christian doxology, and it raises the importance of coral to the Hawaiians, which ties into the archaeological backbone of the piece.

Mobile learning

Studying various factors of engagement, such as motivation, social facilitation, involvement, satisfaction, and knowledge transfer (both direct and tacit). Some of these ideas are extremely simple, such as offering mobile quizzes to users at the real-world referent, as a situated point of learning, and then gauging explicit knowledge transfer. Others are much more complicated, such as trying to figure out how embodiment and haptic perceptions might affect tacit learning.

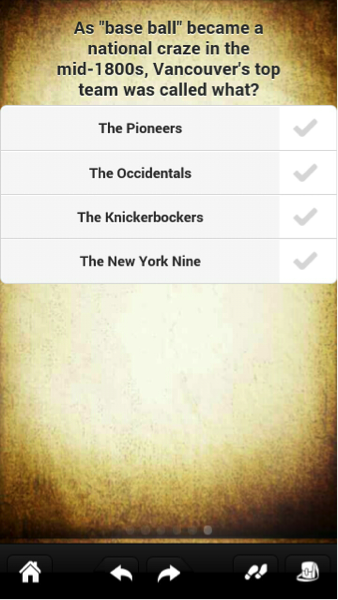

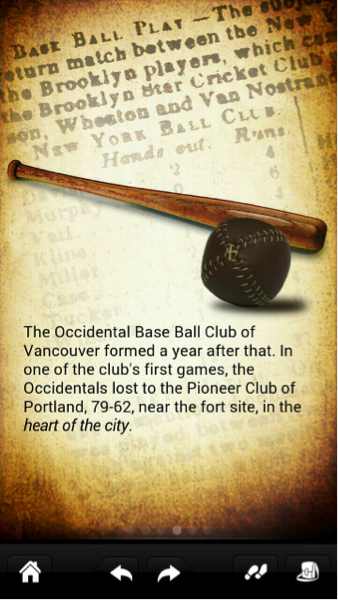

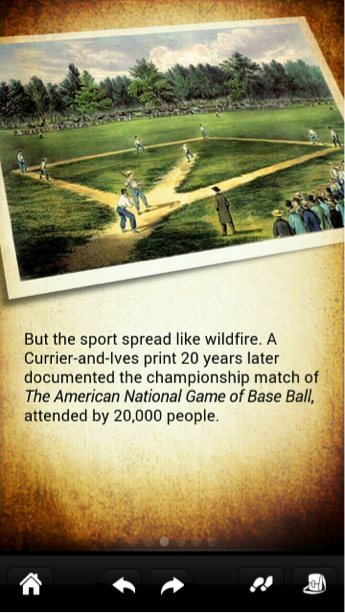

Example: History Quizzes New technologies enable new ways of learning, but they also allow us to reexamine and tweak traditional methods as well. In the Fort Vancouver Mobile app, we experimented with the idea of an embodied quizzing method, in which app users walked around the historic site, trying to find short segments of information (which were pushed to the app at various GPS coordinates, based on the surroundings) followed by a multiple-choice quiz. The example below is from the “base ball” segment, attempting to tie together history external of the site, as in the national development of a sport, with the local effects of the trend.

REFERENCES

Bacher, Kevin, Alyssa Baltrus, Charles Beall, Dominic Cardea, Linda Chandler, Dave Dahlen, Richard Kohen, Becky Lacome, Jana Friesen McCabe and Peggy Scherbaum. 2011. Foundations of Interpretation. Bloomington, IN: Eppley Institute for Parks and Public Lands.

Mackintosh, Barry. 1986. Interpretation in the National Park Service: A Historical Perspective. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Mersey, Rachel, Edward Malthouse and Bobby Calder (2010). “Engagement with Online Media.” Journal of Media Business Studies (2): 39–56.

O’Brien, Heather and Elaine Toms (2008). “What is user engagement? A conceptual framework for defining user engagement with technology.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology59(6): 938–955.

O’Brien, Heather and Elaine Toms (2010). “The development and evaluation of a survey to measure user engagement.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 61(1): 50–69.

Patwardhan, Padmini, Jin Yang and Hermant Patwardhan (2011). “Understanding media satisfaction: Development and validation of an affect-based scale.” Atlantic Journal of Communication 19(3): 169–188.

Taylor, Claire, Min Wilkie and Judith Baser (2006). Doing action research: A guide for school support staff. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.

Whisnant, Anne, Marla Miller, Gary Nash and David Thelen (2012). “The State of History in the National Park Service: A Conversation and Reflections.” The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites 29(2): 246–263.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.