Hacking for Gold

Wednesday, March 30, 2016

Laurel Felt (Student Voice Project)

> > _“YouthBuild Charter School of California] YCSC students, who are all between the ages of 16 to 24 years old, come from low-income families and underserved communities, and have previously left or been pushed out of the traditional school system without a diploma. They enroll at Youth Build programs over-aged, under-credited, or both, in order to receive vocational training, leadership development and an education” (_“ABOUT US: Who We Are,” YouthBuild Charter School of California).

> > “People just have to figure out how to inspire kids” (Menjivar 2014)

From 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. on Saturday, April 12, 2014, the Sage Hall Computer Lab at the Los Angeles Trade and Technical College (LATTC) was humming with activity. The cause was YouthBuild Charter School of California (YCSC)’s WebSlam, an innovative event that served multiple functions. Proclaimed Curren Price, Council member for the city’s economically challenged ninth district which hosted WebSlam, this event both demonstrated and facilitated the rise of “The New Ninth” (“WebSlam a Huge Success,” Suttmeier).

So what was the singular event that honored these educationally and civically meaningful ends? What was WebSlam? According to Tim Falls, Director of Developer Relations at @SendGrid, a better question is why (Falls, “WHY Is a Hackathon?”). This case study will examine YCSC’s WebSlam, articulating why organizers convened a hackathon in south Los Angeles. Next, it will review participants’ educational experiences, examining how they learned through doing and cultivated versatile skills. Finally, it will explore community impacts.

Why WebSlam?

Twenty youth, half of whom are female and all of whom identify as either African-American or Latino, participated in WebSlam, YCSC’s first-ever hackathon. A hackathon is an event in which a large number of people (typically computer programmers, but occasionally graphic designers, interface designers, and other stakeholders also join the mix) collaborate intensively on software projects (“Hackathon,” Wikipedia). But @SendGrid’s Falls seeks to distinguish the objectives and ethos of a hackathon from its rudimentary definition, answering the (albeit colloquially phrased) question, “Why is a hackathon a thing?” (Falls, “WHY Is a Hackathon?”).

For all of these reasons:

Community.

To learn & teach.

To solve problems.

To create something new.

To meet like-minded people.

To build, because building is fun and rewarding.

To gain the respect of peers, through creative expression.

To collaboratively push the limits of technology as we know it today.

Not for all of these reasons:

To help companies sell their product and/or commission free labor.

To launch and/or fund new or existing businesses.

To earn money and win prizes.

YCSC’s WebSlam modeled this approach, prioritizing community and learning above remuneration; as such, hackathons in general and this one in particular might be understood as propelled by intrinsic, rather than extrinsic, motivation (Deci and Ryan 2007). STEM Coordinator Nadia Despenza, organizer of YCSC’s WebSlam and the “go-to” person for all things STEM-related across YouthBuild’s California operations (Nationally, YouthBuild facilitates 273 programs in 46 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, collectively engaging approximately 10,000 young adults per year. Thirteen of YCSC’s 18 schools are in southern California) might add two additional reasons to the list: To facilitate the entry of underrepresented individuals into STEM fields; To engage youth in a civic space.

YCSC STEM Coordinator and WebSlam organizer Nadia Despenza | Photo: Laurel J. Felt

Careers and Community

Recent research suggests that efforts like Despenza’s are sorely needed (Felt, “Hacking for Gold: South L.A. Youths Code Towards a Better Future”). In terms of STEM participation (as measured by rates of taking STEM-related Advanced Placement exams (The College Board, Program Summary Report), earning bachelor’s degrees in computer science (Ashcraft, Eger, and Friend,Girls in IT: The Facts), and performing science and engineering jobs(National Science Foundation 2013)), and females and individuals of African-American and Latino descent are grossly underrepresented. This disparity has major economic implications, both for individuals and for the country.

According to U.S. News and World Report’s 2014 coverage of the nation’s best jobs, web developers — that is, individuals who are “responsible for designing, coding and modifying websites, from layout to function and according to a client’s specifications” — earned a median salary in 2012 of $62,500 (“Best Technology Jobs: Web Developer”). Meanwhile, the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects about 28,500 new web developer jobs will be created from 2012 to 2022; in fact, the next decade demands massively more highly skilled employees across the technology industry (“Best Technology Jobs: Web Developer”). The technology industry is growing, and there is space for our citizens — all of our citizens, including women and people of color — to serve it.

Engaging youth in civic spaces can bring about a world of good. Youth have several gifts to offer a community, including time; ideas and creativity; connection to place; dreams and desires; peer group relationships; family relationships; credibility as teachers; and enthusiasm and energy (Kretzmann 1993). If youths’ assets are aligned with civic purposes, then meaningful growth for both individuals and neighborhoods can result. Civically engaged youth are more likely than uninvolved peers to avoid violence and delinquency, sense community membership, maintain cultural identity, enjoy emotional wellbeing, develop a strong work ethic, pursue education, and obtain employment (Zeldin 2004). Neighborhoods that foster youth service not only reap the benefits of these young people’s engagement but also can become asset-building communities, or communities that “provide a constant and equitable flow of asset-building energy to all children and adolescents” (Benson 2003).

While we tend to think of civic spaces as geographical sites like city libraries or parks, the Project for Public Spaces describes civic spaces as “…settings where celebrations are held, where social and economic exchanges take place, where friends run into each other, and where cultures mix.” As such, digital destinations can function as civic spaces, and research has shown that indeed they do. Moreover, youth civic engagement scholars Joseph Kahne, Nam-jin Lee, and Jessica Feezell have found that nonpolitical online activity (which includes (but is not limited to) participating in a hackathon) “…can serve as a gateway to participation in civic and political life, including volunteering, community problem solving, protest activities, and political voice” (Kahne et al 2013). Therefore, as far as civic engagement is concerned, hackathon’s are a win-win-win.

Educational Impacts

Educationally, WebSlam participants benefited by learning through doing and developing important skills. Learning Through Doing:

> > Participants’ engagement with WebSlam showcased how hands-on, experiential learning, or “learning through doing,” is an effective mode of piquing interest, encouraging ownership, and scaffolding mastery.

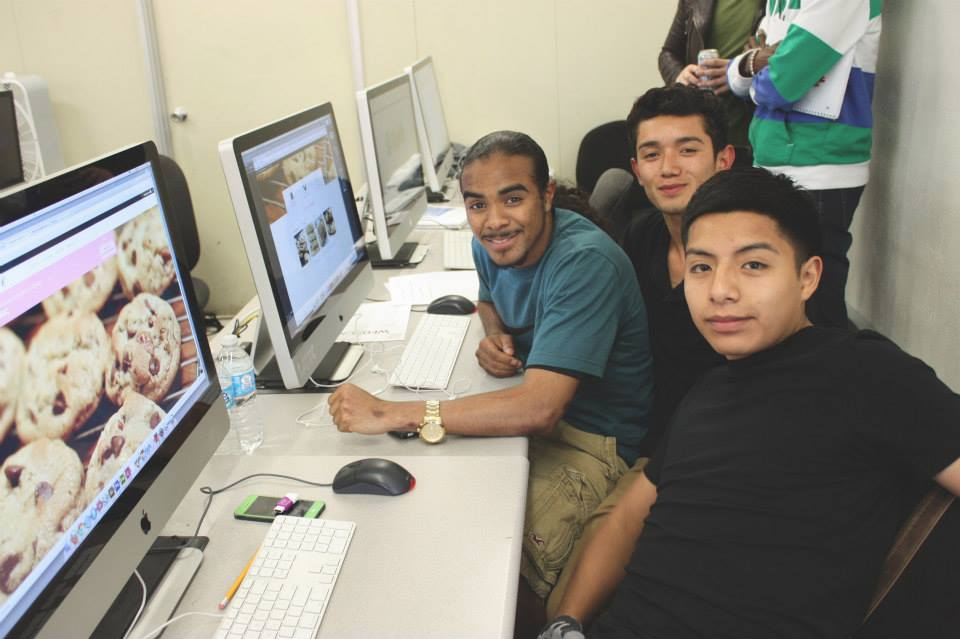

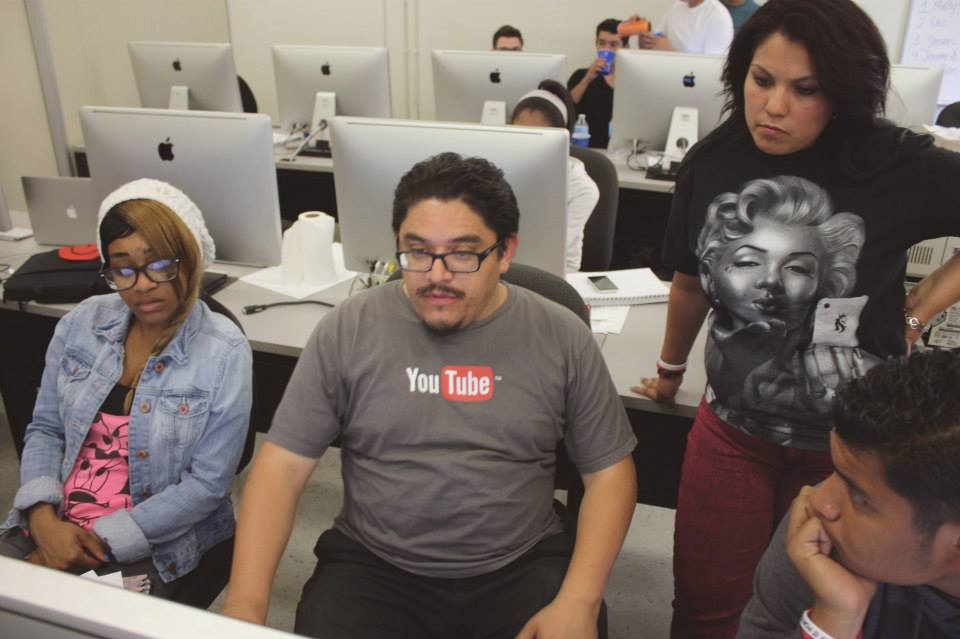

Participants learned to code via five after-school sessions prior to WebSlam. Although daily instruction concluded at 3 p.m., said instructor Oscar Menjivar, “We had students stay until 4 — that’s the time that we stayed. But I think if we were to stay maybe later, until 8 or 9, I think they would have wanted to stay.” His suspicions were confirmed on Saturday, when a team of three young men — Jose Sandoval, Hector Linares, and Michael Taton — refused to take a lunch break. While the trio might have been motivated by their work’s real world relevance (they were creating a site for a LATTC student’s start-up), it is likely that their passion for coding also kept them in their seats. Of coding, participant Taton, 21, a Spring 2014 graduate of CRCD Academy YouthBuild, said, “I just feel I pick it up easy” (Taton 2014).

Menjivar’s “learning through doing” method encourages commitment and autonomy. Inevitably, said Menjivar, after learners gain familiarity with the tools, explore, self-express, believe that it’s okay to fail, and learn how to address setbacks, “they start to have fun. They don’t want to leave the classroom. They’re engaged, they want to talk to each other, they’re asking you questions like, ‘So Oscar, how do I get into more jobs like this?’ ‘So Oscar, where do I go next, where do I find more information?’”

Despenza attested, “Certain participants have found their love for coding and are like, ‘We want to do this, we want to intern somewhere.’”

Skill Development

> > But coding doesn’t call to everyone; some participants indicated that they would rather not “geek out” on WordPress after WebSlam’s conclusion (Ito et al., Hanging Out, Messing Around, and Geeking Out).

They didn’t walk away empty-handed, however; investing in the hackathon provided them with opportunities to enrich several versatile skills. Explained Despenza, “Certain participants have learned, ‘I can do more than I thought I could.’ There was one student in particular — it was rough for him to get it down but he’s here today and he found, ‘I may not do this for the rest of my life, but I can do this if I put my mind to it.’” The significance of lessons such as this, and the value of positive self-talk such as Despenza modeled, is considerable (“Thought Self-Leadership,” Neck and Manz).

Yasmeen Summerlin, 20, an 11th grader at Home Sweet Home YouthBuild who plans to graduate this December, is one of those students who cultivated perseverance. Summerlin doesn’t plan to pursue web development; she wants to become a crime scene investigator, and aspires to enter Boston University’s prestigious forensic science program. “I was going to give up yesterday because my ideas were being shot down and I’m just trying to please people,” said Summerlin. “And when my ideas are being shot down to please people, I’m obviously not pleasing people, I’m not the person you should be working with. But she [her favorite teacher, Despenza] wanted me to stay for this, so then I said, ‘Okay. I don’t throw stuff out’” (Summerlin 2014). Summerlin’s team, which re-designed LATTC’s Cosmetology Department Salon Service, ultimately was awarded second-place.

WebSlammers also practiced communication and collaboration. “[W]hen they first started,” Despenza recalled, “they didn’t know what they were doing, they were a little scared. And then they started to not just work as one but to collaboratively work as a group with autonomy. So they would assign people, like, ‘You’re a great coder, why don’t you do that,’ ‘You’re great at Photoshop, why don’t you do that.’” This is the quintessence of collective intelligence (McGonigal 2008), an important practice for developing and enriching communities.

Community Impacts

YCSC’s WebSlam provided an opportunity for local entities to collaboratively serve the community and realize personally important goals, and for participating students to engage in service learning. Multi-party Collaboration:

Teamwork epitomized the WebSlam experience all parties involved. Despenza contacted Menjivar, who agreed to provide the coding instruction for the WebSlam she envisioned. A mutual acquaintance introduced Despenza to Samantha Walters, Co-location America’s Vice-President of Online Strategy, who provided the necessary sponsorship dollars. Joseph Guerrieri, LATTC’s Dean of Academic Affairs and Workforce Development, volunteered to host WebSlam at the college’s computer lab. Melanie Vaget responded to Despenza’s and Walters’s call for mentors, rounding up a group of her colleagues from L.A.-based tech company Factual.

YCSC’s WebSlam, therefore, identifies various types of community partners who might be incented to support a civic endeavor such as this. It also suggests “self-interest” as a screening criterion — that is, partners must recognize participation as a means by which to achieve an important goal (e.g., satisfying a core personal value, furthering the company’s mission, investing in future earning potentials).

Service Learning

Finally, YCSC’s WebSlam models service learning, defined as “a teaching and learning strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction and reflection to enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities.” WebSlammers provided community service by furnishing four LATTC-associated entities with new websites: 1) LATTC student Hubbard’s local business, Shaquann’sGourmet Cookies; 2) LATTC’s Cosmetology Department’s salon; 3) LATTC’s Transportation Technologies Department’s auto shop; and 4) LATTC’s Associated Student Organization, the college’s student council (Both the salon and the auto shop provide space for LATTC students to hone their respective crafts, earn income as they do so, and provide discounted services to neighbors).

WebSlam participants also engaged in conversation and reflection throughout the day, guided by the imperatives to serve their clients and satisfy the event’s guidelines. Concluding their WebSlam experience, participants presented their websites to their clients before a panel of expert judges and interested community members. In various ways and to multiple constituencies, WebSlam participants’ learning mattered.

Conclusion

This civic media event provided an opportunity for female and minority youth to increase their awareness of STEM-related career paths, deepen civic engagement, learn about coding in a hands-on manner, and cultivate proficiency in several versatile skills. WebSlam partners were able to give back and realize personal goals, local entities received useful new websites, and the community supported service learning. Collectively, this benefits individual participants and facilitates neighborhood revival.

References

Ashcraft, Catherine, Elizabeth Eger, and Michelle Friend. 2012. Girls in IT: The Facts. Boulder, CO.

Benson, Peter L. 2003. “Developmental Assets and Asset-Building Community: Conceptual and Empirical Foundations.” In Developmental Assets and Asset-Building Communities: Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice, edited by Richard M. Lerner and Peter L. Benson, 19–45. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

“Best Technology Jobs: Web Developer.” U.S. News and World Report, 2014.http://money.usnews.com/careers/best-jobs/web-developer.

Deci, Edward L., and R.M. Ryan. 2000. “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being.” American Psychologist 55: 68–78.

Falls, Tim. “WHY Is a Hackathon?” SendGrid, n.d. http://sendgrid.com/blog/why-hackathon/.

Felt, Laurel J. 2014. “Hacking for Gold: South L.A. Youths Code Towards a Better Future.”KCET Departures. May 05. http://www.kcet.org/socal/departures/columns/open- classroom/hacking-for-gold-south-la-youths-code-towards-a-better-future.html.

Ito, Mizuko, Sonja Baumer, Matteo Bittanti, Danah Boyd, Rachel Cody, Becky Herr-Stephenson, Heather A. Horst, et al. 2010. Hanging Out, Messing Around, and Geeking Out. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Jensen, Lene Arnett. 2008. “Immigrants’ Cultural Identities as Sources of Civic Engagement.” Applied Developmental Science 12 (2): 74–83. doi:10.1080/10888690801997069.

Kahne, Joseph, Nam-Jin Lee, and Jessica T. Feezell. 2013. “The Civic and Political Significance of Online Participatory Cultures among Youth Transitioning to Adulthood.”Journal of Information Technology & Politics 10 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/19331681.2012.701109.

Kretzmann, John P. McKnight, John L. 1993. Building Communities from the Inside Out: A Path Toward Finding and Mobilizing a Community’s Assets. Evanston, IL: Center for Urban Affairs and Policy Research.

McGonigal, Jane. 2008. “Why I Love Bees : A Case Study in Collective Intelligence Gaming.” In The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games and Learning, edited by Katie Salen, 199–227. Cambridge, MA: The MIT. doi:10.1162/dmal.9780262693646.199.

National Science Foundation, and National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. 2013. Women; Minorities; and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering: 2013. Arlington, VA. http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/wmpd/.

Neck, Chris P., and Charles C. Manz. 1992. “Thought Self-Leadership : The Influence of Self-Talk and Mental Imagery on Performance.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 13 (7): 681–99.

Pearson, Sarah S, and Heather M Voke. 2003. Building an Effective Citizenry: Lessons Learned from Initiatives in Youth Engagement. Washington, DC: American Youth Policy Forum.

Project for Public Spaces. “What Is a Great Civic Space?” Accessed August 10, 2014.http://www.pps.org/reference/benefits_public_spaces/.

Suttmeier, Emily. 2014.“WebSlam a Huge Success.” YouthBuild Charter School of California. April 16. http://www.youthbuildcharter.org/webslam-a-huge-success.

The College Board. Program Summary Report. New York, 2012.

Wikipedia. “Hackathon.” Accessed July 01, 2014.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hackathon.

YouthBuild Charter School of California. “ABOUT US: Who We Are.” YouthBuild Charter School of California. Accessed June 30, 2014. http://www.youthbuildcharter.org/about-us/who-we-are/.

Zeldin, Shepherd. 2004. “Preventing Youth Violence through the Promotion of Community Engagement and Membership.” Journal of Community Psychology 32 (5): 623–41. doi:10.1002/jcop.20023.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.