Horizontal Networking and the Music of Idle No More

Friday, March 4, 2016

Liz Przybylski (Northwestern University)

Online organizing efforts of Idle No More (INM), referred to as #IdleNoMore, offer a prime example of how a grassroots movement embraces contemporary networking strategies by drawing on digital music distribution, information sharing platforms, and the building of virtual group identities (Simpson 2011, Saccá 2003). The participatory, intentionally non-hierarchical movement began with a teach-in. Concurrently, a Twitter hashtag came into use. The music video “Red Winter,” shared over Twitter, indicates how a fusion of contemporary and traditional music distributed horizontally through social media helped inspire participation in this international organizing effort. Twitter facilitates a logic of networking in which participants connect to ideas and each other laterally. Unlike a hierarchical system of organization, any participant may connect to any other and the system changes quickly to respond to users’ needs.

The trend of #IdleNoMore demonstrates how participants harness social media technology to participate in international organizing.

Rapper Drezus, a Canadian of Cree and Saulteaux ancestry, takes his audience on a tour of public round dance events in the music video “Red Winter.” Showing solidarity across Canada and the U.S., “Red Winter,” directed by Cowboy Smithx, shows sounds and images of round dances at INM events in cities including Winnipeg, New York City, and Ottawa, thus demonstrating commonalities between Indigenous nations across Turtle Island (Alfred 2013). Round dances, which have both ceremonial and social functions, create a circular form that indicates the equality of all participants, while their dynamic formation can also show struggle. In the context of the movement, round dances are used to build community, showing the commitment people have for each other. Beyond group dance, individual dancers show multiple traditions in “Red Winter.” A hoop dancer and break dancer are juxtaposed, showing elements of urban and traditional culture coming together. Many listeners note that the lyrics in the chorus, which reference INM, serve as inspiration.

Participants in #IdleNoMore call attention to movement concerns through messages shared in public forums. Through Twitter, this kind of networking extends beyond physical organizing. Social media platforms offer spaces in which individuals shape their public faces. Not limited to individual profile pages, opportunities to build collective identities online are facilitated through properties of the media (Evans-Cowley 2010). Twitter facilitates collective identity construction: users develop horizontal connections by following and being followed by others, employ hashtags to comment on a shared topic of interest, re-tweet posts, or tweet an image or song connected to a group cause. Combined ease of access and difficulty for central control make Twitter “practically ideal for a mass protest movement” (Grossman 2009). Anyone on a computer or mobile phone can become part of the crowd-sourced narrative. A National Day of Action was held on December 10 2012; there were 14,600 tweets about INM that day.** On January 11th 2013, INM held a Global Day of Action that included a gathering in Ottawa and sympathetic demonstrations across Canada and around the globe. There were 56,954 tweets about INM on this day alone from locations across the world (Ottawa: Full Duplex, 2013).

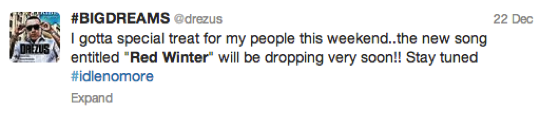

Following the music video’s circulation on Twitter demonstrates how users shape their collective identity through re-manifesting a video that became symbol for a larger movement (Kurzman 2012). At the height of #IdleNoMore during the winter of 2012–2013, Drezus used his own Twitter account to let followers know about the song before it was released:

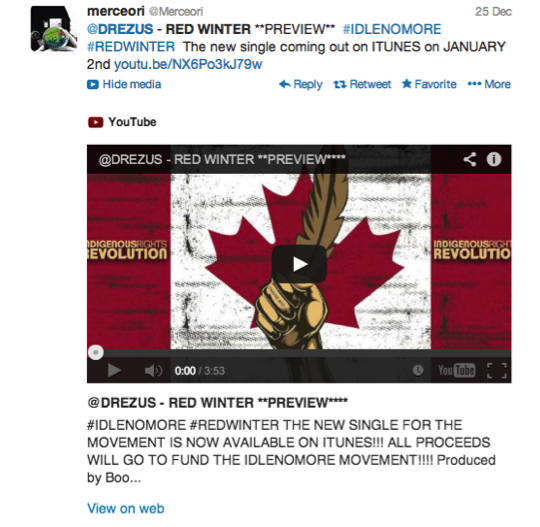

Then, other active users previewed the song:

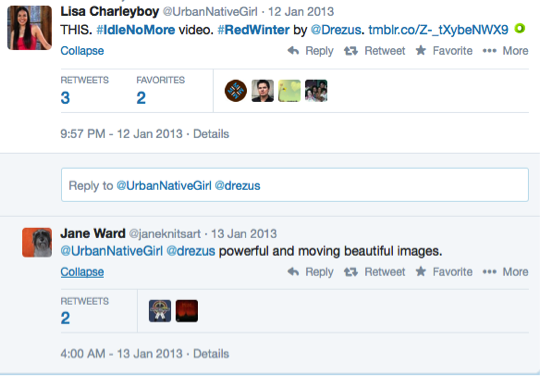

Once released, Twitter participants commented on the video:

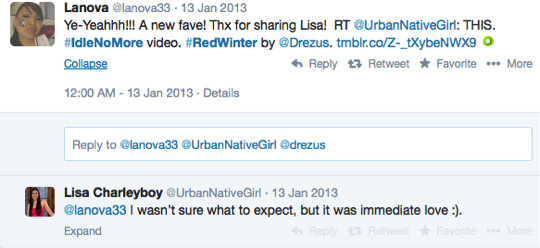

In response, other users re-tweeted and set the tweet as a favorite, sharing it to their networks as well:

As the number of uses of the IdleNoMore hashtag decreased into winter and early spring, individuals tweeted this video with messages to stay inspired, sometimes incorporating #staystrong:

There were also efforts to create new enthusiasm through campaigns like Sovereignty Summer. In May, INM tweeted this video with a message to engage activists for summer events:

Users commented on how the video became an anthem over time:

In August 2013, the video once again surged as the Aboriginal Peoples Choice Music Awards created a buzz around Indigenous popular music. Drezus, who won a 2013 award for the album* Red Winter*, spoke about ongoing treaty concerns when he walked the red carpet for the awards ceremony. After this appearance, INM tweeted the video “Red Winter” once again.

The music video’s circulation required participation from many actors who tweeted links to the video, and after watching it online, left comments and shared it further. Beyond participants who acted in the filming of the music video, activists virtually passed the video on to friends and community members, attaching their own commentary while doing so. People who circulate a music video through social networks participate in the life of the song and help determine who hears its message. Online commentators interpret the music and, as evidenced online, the original artists and producers reply to these posts (This music video also had an offline life, playing for example in a film festival. While connections between online and offline organizing extend beyond the scope of this case study, it should be noted that the circulation of this online material had offline resonances).

#IdleNoMore takes advantage of the aspiration-ally non-hierarchical nature of connectivity through Twitter. There is possibility for other grassroots use of online music sharing as any user with a mobile device and an Internet connection can become a newsmaker, even without the sanction of an official organization. Open access does come with risks. For Twitter to become an effective part of a larger grassroots strategy, it is important for participants know its limitations, including a potential for account hacking or the possibility that non-involved users might employ a popular hashtag to promote unrelated ideas or products. At its best, the circulation of music through Twitter allows diverse individuals to shape a public voicing of concerns. Through this dynamic process, ideas emerge and change in this sometimes messy but always participatory form. This networking logic that incorporates low barriers of entry and horizontal connections between participants allows musicians and other participants to share ideas, call for action, and offer time and skills for a shared cause.

References

Evans-Cowley, Jennifer S. 2010. “Planning in the Age of Facebook: The Role of Social Networking in Planning Processes.” GeoJournal: Spatially Integrated Social Sciences and Humanities 75 (5): 407–420.

Full Duplex. 2013. Idle No More at Six Months: Analysis of the First Six Months of the Idle No More Movement. Ottawa: Full Duplex.

Grossman, Lev. 2009. “Iran Protests: Twitter, the Medium of the Movement.” Time, June 17.

Kurzman, Charles. 2012. “The Arab Spring: Ideals of the Iranian Green Movement, Methods of the Iranian Revolution.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 44: 162–165.

Saccá, Elizabeth J. 2003. “Art, Native Voice, and Political Crisis,” Visual Arts Research 29 (57): 80–88.

Simpson, Leanne. 2011. Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back. Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring Pub.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.