Kony 2012: Using Technology for Empathy

Wednesday, April 6, 2016

Margie Dillenburg (Former Chief Operations Officer, Invisible Children)

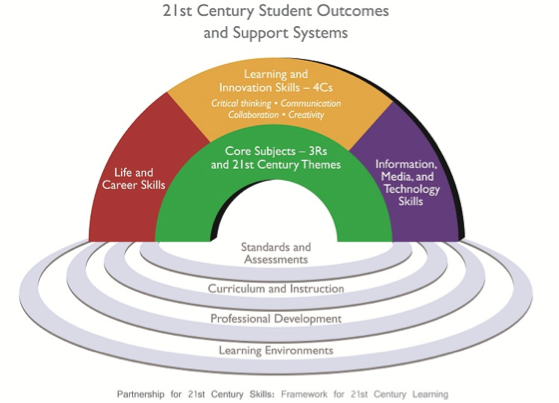

The term empathy has recently been on the minds of philosophers (Krznaric 2012), neurologists (Decety and Ickes 2009), health care professionals (Spiro 1992; VanHooft 2011), social workers (Gerdes, Importance of Empathy for Social Work Practice: Integrating New Science 2011), educators (Brooks 2009; Endacott 2010; Yilmaz 2007), and in the media (First Read Minute 2014). Empathy, though simply defined as one’s ability to comprehend the situation of another, is a complex process of the mind and heart (Gerdes 2011; Davis 1980). Findings connect it to a myriad of pro-social outcomes such as helping behavior (Graziano, Habashi and Sheese 2007), cooperating skills, self-esteem, and civic engagement (Noddings 2002). It also has inverse associations with bullying, racism, depression, and aggression (Legault, Gutsell and Inzlict 2011). In education particularly, there has been an emerging focus on building “21st Century Skills,” increasing the spotlight on empathy building in schools (Framework for 21st Century Learning 2010).

These 21st Century Skills require students to cooperate and communicate across cultural lines, to have a command of technology, and to demonstration imaginative problem solving skills, all of which relate to empathy. They are also represented in the engagement model of *Kony 2012* and its parent organization, Invisible Children(Russell 2012). For this reason Invisible Children was a fixture in many schools prior to the release of Kony 2012.\ Educators identified Invisible Children’s engagement programs as a way to teach 21st Century skills and empathy (Kligler-Vilenchik and Shresthova 2012).

> > This viral phenomenon provides an opportunity to examine the opportunities when technology, film, and sound educational pedagogy are used to engage millennials’ empathic potential.

*For those unfamiliar with Invisible Children, or need a reminder of what happened when Kony 2012 went viral, this figure to the left gives a visual and numerical overview. It represents a breakdown of Kony 2012’s conception, execution, life-span, and results, as reported by Invisible Children.

To view Invisible Children and Kony 2012 as an empathic case study, the term “empathy” must be further clarified. Researchers agree that empathy occurs both intellectually and emotively (Davis 1980; Preston and DeWaal 2002). This dual-process function combines a neurological reflex (mirror neurons) (Gutsell and Inzlicht 2010), and learned skill (Spiro 1992). Though some people are born with empathic predispositions, empathy can be fostered intellectually and emotionally (Mehrabian, Young, and Sato 1998). The tool often used to measure empathy levels is the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) (Davis 1983). The IRI is based on four subscales, two that are cognitive (c) and two emotional (e); imagination (c), perspective taking (c), affective connection (e), and personal distress (e). These subscales offer the theoretical framework from which to examine the case of Invisible Children and Kony 2012. Through the use of technology, social media, and film, this organization inadvertently put millennials in an empathic pipeline that aligns with these subscales.

For most, Kony 2012 was the first experience with Invisible Children, though the decade-old organization has made hundreds of podcasts and films. The story structure of their film is simple: a westerner is introduced on-screen; the viewer would affectively connect to him/her. he westerner would make a connection with a war-affected peer in northern Uganda, and the audience would be gently guided into that connection as well. This method of reporting and storytelling is not unique, especially for those telling the stories of people in distant places. In a youtube question and answer session, Nicholas Kristof discusses a “white arc” that he uses to emotionally scaffold his readership into a connection to a far off humanitarian crisis (Kristof, Youtube Question on Africa Coverage 2010). Normally, distance is a barrier to empathic connection (Ginzburg 1994), so Invisible Children’s the use of visuals and Kristof’s “arc” help overcome that geographical barrier. Next, the open sourcing of podcasts, webinars, school assembly and classroom screenings offered a multi-sensory entry point, which was both engaging and easy to virtually share. This method of story telling helps forge an empathic connection with a world issue that many are overwhelmed by. In this way an “affective connection” is formed, marking the first step in a viewers’ empathic engagement.

Invisible Children capitalizes on audiences’ emotional investment to impart the context and the scale of the issue. The affective connection creates a motivational effect so statistics that might otherwise be boring are now interesting (Kristof, New York Times Op Ed 2007). The use of animation sequencing, re-enactments, and real-time footage, Invisible Children kept engagement high and compelling, helping viewers through the “perspective-taking” phase of empathy. After that, the films’ story arc reaches a climax — the viewer is guided toward a feeling of “personal distress.” Upon feeling the affective connection to a victim in crisis, gaining an understanding of context and scale (“perspective taking”), audiences begin to sense an urgency of the situation in real time. At this point viewers are still only partially through an empathy building process. Viewer empowerment is the next necessary step in that process, and required to set viewers up to engage in “helping behavior” outcomes. At this point of experiencing “personal distress,” one’s brain seeks relief in one of two ways: constructive action, or avoidance/redirection. Avoidance often looks like “compassion fatigue” and burn out (Batson, Fultz and Schoenrade 1987).

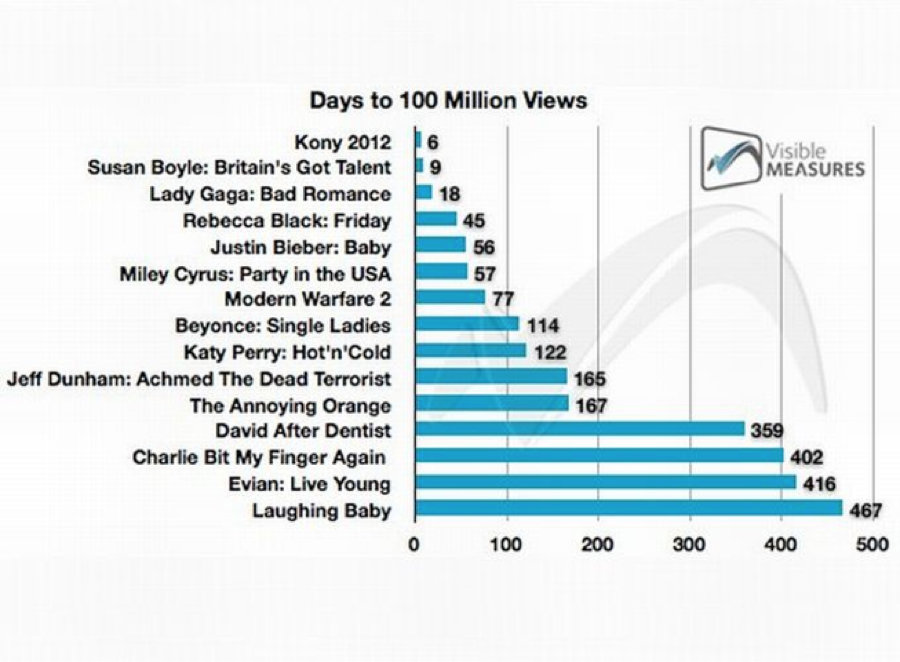

It is here that Invisible Children’s strategy is to first cast a vision to end the crisis, and then to invite the viewer toward constructive engagement (relieving personal distress). The empowerment message was made even more effective through the medium of film because a movie literally offers a vision of what can be, igniting the “imagination” aspect of empathy (Davis 1983). Audiences, therefore, are carefully guided through the four clinical requirements of empathy in an artful and pedagogically sound way. Kony 2012mirrored this empathic journey, and viewers of the film responded just as empathy research would suggest, by participating in helping behaviors (Preston and DeWaal 2002). Though controversial, this 30-minute film about a remote war was the most shared video in history. It broke expectations of millennials’ apathetic nature, and gave insight on how to tap into the empathy and desirable pro-social behaviors of this generation.

This is the empathic pipeline is represented throughout Invisible Children’s overall brand engagement strategy. After every film or online experience, the audience is individually connected with a peer mentor who can guide them toward customized involvement, and can encourage the empathic process along in a nuanced manner (Dillenburg 2009). Local supporter communities are formed and are connected through online platforms to motivate each other. Webinars and curriculum enhance their cognitive understanding and perspective of the problem, as well as real time updates on crisis were available through their innovative crisis tracker (LRA Crisis Tracker n.d.) (therefore sustainable level urgency, or “personal distress”) (Cameron and Payne 2011; Kony 2012 Campaign Analysis 2012). All of these elements combine to positively effect the empathy skills of millennials, and as a bonus, they made it all fun.

REFERENCES

Batson, C. D., J. Fultz, and P. A. Schoenrade. 1987. “Distress and Empathy: Two Qualitatively Distinct Vicarious Emotions with Different Motivational Consequences.”Journal of Personality 55 (1): 19–39.

Brooks, Sarah. 2009. “Historical empathy in the social studies classroom: A review of the literature.” The Journal of Social Studies Research 33(2).

Cameron, D., and K. Payne. 2011. “Escaping Affect: How Motivational Emotional Regulation Creates Insensitivity to Mass Suffering.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100 (1): 1–15.

Davis, M. H. 1980. “A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy.”JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology 10 (85).

Davis, M. H. 1983. “Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44 : 113–126.

Decety, J., and W. Ickes. 2009. The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Dillenburg, Margie. 2009. “Invisible Children Curriculum.” Invisible Children, Inc. . Invisible Children. http://invisiblechildren.com/get-involved/start-a-club/ (accessed June 30, 2014).

Endacott, J. L. 2010. “Reconsidering affective engagement in historical empathy.” Theory & Research in Social Education 38: 6–49.

First Read Minute. 2014. NBC. January 7. http://firstread.nbcnews.com/_news/2014/01/07/22217507-first-read-minute-what-gop-empathy-gap-means-for-party-2014 (accessed July 20, 2014).

“Framework for 21st Century Learning.” Partnership for 21st Century Skills. 2010. http://www.p21.org/about-us/p21-framework (accessed June 30, 2014).

Gerdes, K. 2011. “Empathy, Sympathy, and Pity: 21st Century Definitions and Implications for Practice and Research.” Journal of Social Services Research 37.

Gerdes, K. 2011. “Importance of Empathy for Social Work Practice: Integrating New Science.” Social Work 56 (2).

Ginzburg, Carlo. 1994.”Killing a Chinese Mandarin; The Moral Implications of Distance.”Critical Inquiry 21 (1): 46–60.

Graziano, W., M. Habashi, and B. Sheese. 2007. “Agreeableness, Empathy, and Helping: A Person X Situation Perspective.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 93 (4): 583–599.

Gutsell, Jennifer, and M. Inzlicht. 2010. “Empathy constrained: Prejudice predicts reduced mental simulations of actions during observations of outgroups.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 46 (5): 841–845.

Invisible Children Youtube Channel. 2009. http://invisiblechildren.com/program/schools-for-schools/ (accessed June 30, 2014).

Kligler-Vilenchik, Neta, and Sangita Shresthova. 2012. “Learning Through Practice: Participatory Culture Civics.” Los Angeles, CA: Annenberg School for Communcation and Journalism.

Kristof, Nicholas. 2007. “New York Times Op Ed.” New York Times. May 10. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/10/opinion/10kristof.html?_r=0 (accessed July 20, 2014).

Kristof, Nicholas. Youtube Question on Africa Coverage New York Times, (July 9, 2010).

Krznaric, Roman. RSA Animate. December 12, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BG46IwVfSu8 (accessed July 20, 2014).

Legault, Lisa, Jennifer Gutsell, and Michael Inzlict. 2011. “Ironic Effects of Antiprejudice Message: How Motivational Interventions Can Reduce (but also increase) Prejudice.”Psychological Science 22 (12): 1472–1477.

“LRA Crisis Tracker.” Invisible Children; Resolve. http://www.lracrisistracker.com/(accessed June 30, 2014).

Mehrabian, A., A. L. Young, and S. Sato. 1998. “Emotional empathy and associated individual differences.” Current Psychology: Research & Reviews 7.

Noddings, Nell. 2002. Educating Moral People: A Caring Alternative to Character Education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Preston, S., and F. DeWaal. 2002. “Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases.” Behavioral and Brain Science 25: 1–72.

Kony 2012. Directed by Jason Russell. Produced by Invisible Children. 2012.

Spiro, H. 1992. “What is Empathy and Can it be Taught.” Annals of Internal Medicine 116 (10).

VanHooft, S. 2011. “Caring, objectivity and justice: An integrated view.” Nursing Ethics 18 (2): 149–160.

Yilmaz, K. 2007. “Historical empathy and its implication for classroom practices in schools.” The History Teacher 40 (3).

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.