Mashnotes

Thursday, March 3, 2016

Roy Bendor (The University of British Columbia)

Over a period of two weeks in spring 2011, Vancouver residents were invited to voice their opinion on the city’s urban design by interacting with three kiosks that were placed at central locations in the city’s downtown (see figure 1). Each kiosk featured a different question pertaining to one of the city’s high-profile urban design issues, inviting people to vote by pressing one of two clearly marked buttons located immediately below a slender screen (see figure 2).

The kiosk on Granville Street provided a choice between inner-city densification, and expansion of the highway system that links Vancouver with other Lower Mainland communities. The question read, “Should we create more density in the city and expand laneway housing or create projects like the Gateway to make it easier to get to the suburbs?” and the two potential answers were “laneway” and “gateway.” The kiosk at the Woodward’s Building atrium offered a choice between high-rise and low-rise architectural styles, asking: “Vancouver is a young city whose look has shifted with the trends. What should be our signature architectural style?” The two alternatives were “super-tower” and “low-rise.” And the kiosk at the Roundhouse Community Centre provided a choice between green and social public spaces, inquiring: “What is more important, spaces like the seawall or places where we can see wall to wall people?” Possible choices were “sea” and “be seen.”

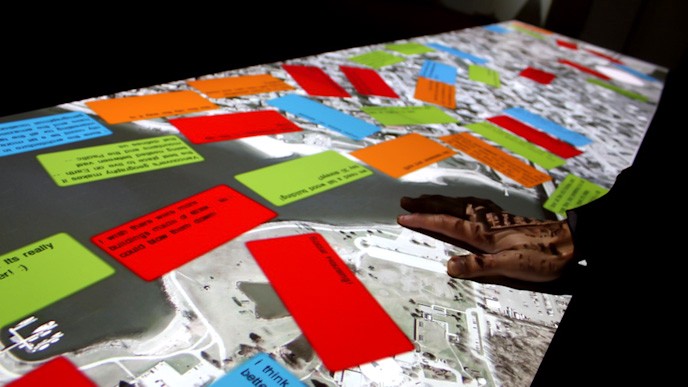

The three kiosks were part of an installation titled Mashnotes, named after the childhood game of Mansion, Apartment, Shack, and House. It was commissioned by the Museum of Vancouver (MOV), was funded by a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, and created by Vancouver-based design outfit, Tangible Interaction. Votes cast through the kiosks were collected using the Arduino open-source microcontroller platform, sent over the cellular (GSM) network, and collated with the votes sent by text messages (SMS) and through the project’s (now defunct) website. All votes were then aggregated and displayed as a set of live data visualizations projected on large screens at the MOV’s main gallery space (see figure 3). The museum’s gallery also featured a light table that allowed visitors to pose open-ended questions and interact with them by using natural hand gestures (figure 4). Altogether, more than 2000 votes were cast, tallied, and visualized.

> > Mashnotes was timely. Not only was Vancouver celebrating its 125th anniversary, the city was also in the process of revisiting its growth strategy and revising several of its long-term development plans.

These coincided with the city’s ambitious plan to become “the world’s greenest city by 2020.” Taking advantage of this momentum, the installation was meant to “hold a mirror up to the city and lead provocative conversations about its past, present and future.” And indeed, as told by the installation’s designer, Alex Beim, “On the city streets in particular, we noticed people didn’t just walk up to the Mashnotes Voice It kiosks, read the question and simply press an answer button. They’d actually start debating the topic with their friends or family right there. We’ve no way of knowing if those conversations continued or if they led to any action but it’s a pretty good indication that the installations sparked something.”

While the kiosks may have provoked lively conversations about some of the dilemmas facing Vancouver’s urban design and city planning, one may ask whether that was all they provoked. Could it be that the installation sparked curiosity about civic policymaking in general, or a sense of agency, evoked by the kiosks’ voting mechanism and invitation “to have a direct say”? The noticeable lack of information regarding the issues would indicate that the installation served more to instigate than to educate. Additionally, the fact that the City was not involved in funding or designing Mashnotes, and was not committed to integrating any of the opinions expressed through the kiosks into actual policy, would militate against a perception of the installation as an official surveying device or a direct channel between citizens and policymakers. Perhaps a shift in attention from the installation’s context to its actual affordances, would reveal a different kind of politicizing potential at play here. In this vein, while bearing in mind Anthony Dunne & Fiona Raby’s (Dunne & Raby 2013, 37) cautioning that “the power of design is often overestimated,” it could be suggested that what the installation sparked was a sense of urban design itself as a space of contention, that is, an object of politics.

In this reading the installation’s rudimentary interactive affordances take on new significance. When considering the kiosks’ provocative phrasing of the questions, the avoidance of engineering or bureaucratic jargon, and the way choices were posed as contrasting dyads, Mashnotes can be seen as an instance of what Carl DiSalvo (DiSalvo 2012, 2) calls “adversarial design”: “a kind of cultural production that does the work of agonism through the conceptualization and making of products and services and our experiences with them.” So while the installation may have stripped away some of the complexity and ambiguity that are inherent to Vancouver’s urban design, it also signified the latter as a set of irreducible tradeoffs — revealing the tensions that underlie it as an essentially contested space. In this sense, the installation provided the public with an opportunity to perform the conflictual nature of urban design, and to experience it as an element of civic politics.

REFERENCES

Dunne, Anthony & Fiona Raby. 2013. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

DiSalvo, Carl. Adversarial Design. 2012. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.