Meu Rio

Thursday, March 3, 2016

Joshua Goldstein (Princeton)

For several days in June 2013, sparked by rising bus fares, millions of Brazilians took to the streets in protest, expressing collective frustration with the state of public life. For many young people, attending the protest was their first civic action. While the protests dissipated quickly, survey data (Mosley 2103) confirm that for many Brazilians, a deep sense of frustration remains palpable.

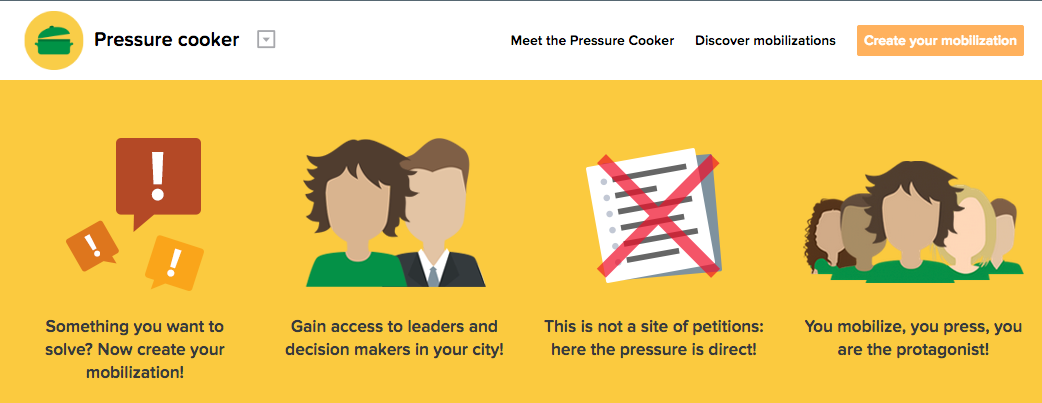

In Rio de Janeiro, an organization called Meu Rio is channeling some of this frustration towards solving tangible problems of urban life. Launched in September 2011 and incubated by Purpose, a civic technology incubator, Meu Rio’s most prominent app is the “Pressure Cooker”, a tool that allows anyone to launch a campaign about a specific local issue in Rio, choose the exact decision maker to solve this problem and build pressure via Facebook, Twitter, and in-person meetings with decision makers.

Meu Rio is built on the proposition that the city is the best place for participatory democracy, and over 120,000 Carioca (citizens of Rio) have participated in dozens of Meu Rio campaigns of varying size and success. One of their most notable successes is a 2012 Pressure Cooker campaign launched by an 11 year student describing how much she loved the Friedenreich Municipal School, a top public school slated for demolition along with the Museu do Índio (Indigenous Museum) in anticipation of the World Cup. Five days before a planned meeting between the government and parents, Meu Rio publicized the campaign, garnering 15,000 signatures as well as a crowd funded effort to cover the transportation costs for students and parents to get to the meeting. The planned demolition was halted soon afterwards.

Meu Rio’s rise to prominence stems at least in part from its ability to serve both as a platform for individual self-expression and as an entry-point to pragmatic institutional politics. Recent protest movements globally, from Zucotti Park to Taksim Square, emerged from a collective sense of indignation with the level of inequality. While these movements have been sources of self-expression and personal transformation for many participants, they have ultimately suffered from an unwillingness or inability to engage in the type of pragmatic politics required for enduring and inclusive political change (Kreiss 2013).

> > Meu Rio occupies a promising middle ground, giving participants a clear entry point to pragmatic politics while at the same time relying on the same performative self-expression that brought so many Brazilians to the streets in protest.

The campaign for the Friedenreich Municipal School demonstrates two of the most powerful aspects of Meu Rio’s approach. First, Meu Rio campaigns addresses Brazil’s biggest problems through specific neighborhood issues. Some Brazilians lost interest in the 2013 mass protests in part because the leaders spoke in generalities about “improving governance” or “ending corruption”, issues that are simply too abstract in a country that is both large and politically opaque. Meu Rio campaigns, on the other hand, draw support from families directly affected by a specific decision, in this case families with children attending the school, and a broader set of activists eager to take on a major challenge at the community level. Second, Meu Rio engages in a very public dialogue with decision makers, which can sometimes lead to swift change. When an important ferry started charging for overweight luggage, which included student backpacks, a campaign targeting the Transportation Secretary took only a week get the decision reversed.

Meu Rio’s success is only growing, and they are currently planning to expand their apps to reach citizens in over 20 Brazilian cities over the next five years (funding for this expansion comes in part from Google’s Global Impact Awards). This success makes Meu Rio an exciting testing ground for at least two of the most important unanswered questions for activists seeking to build the next generation of civic apps.

First, how can app makers like Meu Rio use data to identify when an individual might be “susceptible” to participating in a civic campaign? A new generation of tools creates data exhaust that can be linked to sources such as the Facebook Social Graph API and Twitter API, which in turn can lead to easier identification of friends who might participate. The 2012 Obama campaign took advantage of this opportunity by creating as “influence graph” that used predictive models to match existing supporters with potential targets for persuasion, volunteering and voter registration. The technology behind the tool, now a company called Edgeflip, is now more widely available than ever.

Second, do new civic tools increase or decrease inequality? Meu Rio undoubtedly increases the number of citizens involved in civic life, but are they amplifying the voices that are already being heard? A recent study4 asked a similar question about Get Out The Vote (GOTV) campaigns in the United States and found that many of the campaigns that most improved voter turnout actually contributed to inequality by turning out individuals who, by their socioeconomic and demographic background, are already most represented in the voting population. To be sure, under-represented groups are always the hardest and most expensive to mobilize for any civic activity, yet in democracies like Brazil and the United States, even tiny differences in the type of voices that are heard make an enormous difference in political and policy outcomes.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.