Padres y Jovenes Unidos: A Case Study of Student Empowerment through Critical Media Literacy

Wednesday, March 30, 2016

Lynn Schofield Clark (University of Denver)

Digital Media Club is an extracurricular digital media literacy effort that I started in 2011 with a staff person at one of Denver’s most ethnically and economically diverse urban high schools. The club brings university students and high school students together on a weekly basis in an effort to support the high school students as they seek to “use media to make a difference in their communities.”

The club’s focus is rooted in ideas of critical digital media literacy as students both critically evaluate and create media (see, e..g., Hobbs, 2010; Kellner & Share, 2005; Livingstone, 2004; Thevenin, 2012; Turner, 2011). Throughout the school year, students are encouraged to think about what community they would like to change, what difference they would like to see, and how they might utilize media to bring about this change. The program’s design therefore draws upon concepts of political and civic education in that we recognize the need for relevant and deep knowledge about the roots of social problems, and encourage the students to think about “what is” and “what ought to be (see, e.g., Gordon, 2013; Levin, 2011).”

In our desire to foreground using media to create change, we’ve also had to address the “audience problem” of youth media in creative ways, because as Peter Levine (2008) has pointed out, youth media programs tend to focus on the production of student voice rather than on its reception (see also Soep, 2006, 2011). . This case study discusses how we helped students to experience empowerment as they thought not only about the audience for their particular media product, but also about how their media efforts fit with the larger efforts of a local grassroots organization; an organization that had long been working for better educational outcomes in economically challenged communities like theirs. By playing a role in that organization’s expansive reach, the students were contributing to expanding the audience for the organization’s efforts; thereby channeling their energies toward broader efforts that were already making a difference in the bigger community. In this way, this case study is an example of an alliance-oriented digital media literacy project — an exploration of what happens when digital media literacy is positioned at the core of civic education in an effort to push further the agenda that’s become known as “participatory politics,” or the effort to link student interests and digital media enthusiasm with political initiatives (Mihailidis, 2009; Mihaidilis & Thevenin, 2013). This experience has convinced me that partnering such programs with longstanding community activist groups is a way in which students can experience a more sustained approach to political engagement, and it’s therefore a model I’d like to see tested and developed further.

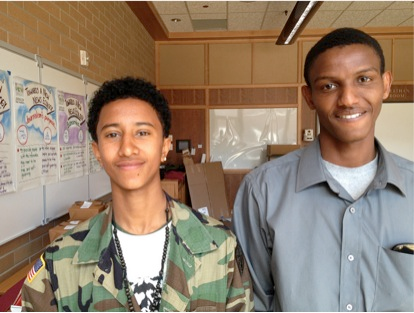

Our school/community partnership began when two of the students in Digital Media Club, Ezana and Karim, introduced the group to the work of Padres Y Jovenes Unidos (Parents & Youth United, or PJU), a group that started in Denver and that was engaged in a campaign that PJU called “End the School to Jail Track.” Their target was zero tolerance approaches to discipline that disproportionately affect students of color in schools across the United States. As part of the campaign, PJU produced a report demonstrating that police involvement in high school discipline had resulted in an increase in school suspensions; showed that there was a link between increased suspensions and higher high school dropout rates, which in turn related to higher rates of incarceration. PJU wanted to turn this around by limiting police presence in schools and by offering support for more effective in-school disciplinary policies so that vulnerable populations would stay in school and out of jail. With funding to implement pilot projects they developed alternatives to the “zero tolerance” approach. They established several restorative justice programs in urban high schools that encouraged students to assume responsibility for repairing the damages that they caused. PJU regularly held rallies to increase support for their efforts statewide.

When Ezana learned that students in another high school had developed a skit to illustrate the differences between punitive and restorative approaches to discipline, he and his peers sought to create a similar skit for their own school, working with Digital Media Club to help film it. The student leaders cast fellow students in the roles of fighting students, stern security officers, a traditional principal who embraces first a punitive and then a restorative justice approach, and a restorative justice counselor who works with the students to discuss what each can do to address and be accountable for the consequences of their actions.

The students took great joy in writing and filming the skit. While filming the fight scene, lots of laughter ensued as the school’s security guards actually showed up to see what all the noise was about. And once the filming and editing were complete, the students circulated the video wide across their social media networks. They also shared it with teachers and with the school’s principal, who — much to the students’ delight — used it in a teacher/training event to demonstrate the value of embracing a restorative justice approach in their school. This was only possible because their work was linked to the wider efforts of PJU that had already gained a place on the school’s agenda.

While the students were planning and filming the skit, the larger PJU organization continued to work with the Denver Public Schools to craft a new discipline policy that limited the police presence in schools and that outlined protections for students and their families. They also worked with the state senate to craft what came to be known as the “smart discipline” bill that aimed to expand the policy into a statewide law. As the bill moved through the state senate, the students involved in the Digital Media Club followed the news and kept their friends updated. When the state senate passed the bill at the end of the school year, the students were overjoyed. They knew that they had expanded PJU’s work in their own school, and so they experienced themselves as participants in the larger political action and felt a great deal of ownership in the bill’s success.

A year after many of the students involved had graduated from high school and two years after creating and circulating among their networks their skit about restorative justice, President Obama suggested making “smart discipline” a national priority. And those students who had worked on using media to envision “what ought to be” could feel pride in knowing that their efforts had joined with many others to bring about political change that would affect their communities for years to come.

This case shares important similarities with a number of “participatory politics” efforts taking place in relation to digital media literacy programs in that it involves following young people as they define the political issues of concern to them and as they decide upon the strategies they would like to embrace (Banaji & Buckingham, 2013; Bennett, 2008; Dahlgen, 2012; Flanagan, 2013; Soep, 2014). What was particularly unique about this instance was that it situates individual political agency in the context of larger and more long-term efforts to bring about positive social change; and it focuses on changes that are deemed important within the context of many disenfranchised communities, drawing upon frameworks from social movement and political mobilization theories (Gordon, 2009; Lipsitz, 2005).

> > The students’ work in creating a story of “what ought to be” and circulating it among their communities helped them see themselves as communicators who were part of an effort to address injustices in their community — an effort that had begun before them, and that would continue long after after their own direct involvement ends.

Through their ability to connect media literacy with civic engagement activities, they came to see the value in organizations like Padres Y Jovenes Unidos that serve a watchdog function in connecting community concerns with political initiatives. And their work both in their local situation and in relation to a much broader information campaign therefore enabled them to draw a connection between their own stories and concerns and those of their communities. Through their involvement in a critical digital media literacy effort, they came to see themselves as engaged in a much broader effort of political reform toward “what ought to be” in our public schools.

REFERENCES

Banaji, S. and Buckingham, D. (2013). The Civic Web: Young People, the Internet, and Civic Participation. The John C. & Katherine T. MacArthur Series on Digital Media and Learning). MIT Press.

Bennett, W. Lance. (2008). Changing citizenship in the digital age. In W.L. Bennett, Civic Life Online: Learning how digital media can engage youth.(pp. 1–24) Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dahlgen, P. (2012). Young citizens and political participation in online media and civic cultures. Taiwan Journal of Democracy 7(2): 11–25.

Flanagan, C. (2013). Teenage citizens: The political theories of the young. Harvard University Press.

Gordon, E. (2013). Beyond participation: Designing for the civic web. Journal of Digital and Media Literacy 1(1).

Gordon, H. (2009). We Fight to Win: Inequality and the Politics of Youth Activism. Rutgers University Press.

Hobbs, R. (2010). Digital and media literacy: A plan of action. Aspen Institute. Retrieval: http://www.knightcomm.org/digital-and-media-literacy/

Kellner, D. & Share, J. (2005). Toward critical media literacy: Core concepts, debates, organizations, and policy. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 26(3): 369–386

Levin, D. (2011). ‘Because it’s not really me:’ Students’ films and their potential as alternative media. (pp. 138-). In JoEllen Fisherkeller (Ed.),International Perspectives on Youth Media. New York: Peter Lang.

Levine, P. (2008). A public voice for youth: The audience problem in digital media and civic education. In L. Benett, ed., Civic Life Online: Learning How Digital Media Can Engage Youth. The John D. & Katherine T. Macarthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008, 119–138

Lipsitz, George (2005). Midnight’s children: Youth culture in the age of globalization. In Sunaina Maira and Elisabeth Soep (Eds.), Youthscapes: The popular, the national, the global. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

Livingstone, S., (2004). What is media literacy? Intermedia 32(3): 18–20

Mihailidis, P. (2009). The new civic education: Media literacy and youth empowerment worldwide. Report. Wash DC: Center for International Media Assistance at the Center for Democracy. Retrieved from :http://cima.ned.org/publications/research-reports/media-literacy-empowering-youth-worldwide.

Mihaidilis, P. & Thevenin, B. (2013). Media literacy as core competency for engaged citizenship in participatory democracy. American Behavioral Scientist 57(11): 1611–1622.

Soep, E. (2006). Beyond literacy and voice in youth media production. McGill Journal of Education 41(3): 197–212.

Soep, E. (2011). All the world’s an album: Youth media as strategic embedding. (pp. 246–261). In Joellen Fisherkeller, ed., International Perspectives on Youth Media: Cultures of Production and Education. New York: Peter Lang.

Soep, Elisabeth, 2014, Participatory Politics, MIT Press.

Thevenin, B. (2012). Critical media literacy in action: Uniting theory, practice and politics in media education (unpublished dissertation) U of Colorado, Boulder

Turner, K.(2011).Mapping the field of youth media organizations in the United States. (pp. 25–49). In Joellen Fisherkeller, International Perspectives on Youth Media. New York: Peter Lang.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.