Race to the White House

Thursday, March 24, 2016

Antero Garcia (Colorado State University) and Ellen Middaugh (Civic Engagement Research Group)

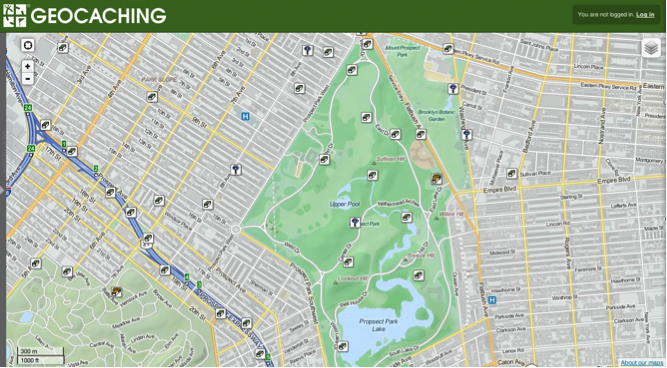

This case study looks at the civic learning opportunities afforded by geospatial play. Briefly, geocaching as described at geocaching.com as “a real-world, outdoor treasure hunting game using GPS-enabled devices. Participants navigate to a specific set of GPS coordinates and then attempt to find the geocache (container) hidden at that location.” This case study highlights how geocaching was used to sustain civic learning opportunities for youth. Through a program developed by Global Kids Inc., participants engaged in a summer-long process of finding, placing, and interacting through the geocaching network, all while discussing electoral topics. This case study can offer pictures, examples, and a theoretical grounding for how civic learning can be uprooted from books and digital screens for learners today.

“They Had Us searching for caches in the woods, and I’m not too friendly with bugs so it was really hard for me to participate because i really Dislike being in the woods where there’s all different types of bugs around.” — Race to the White House Participant, July, 2012

In 2012, 14 high school youth engaged in a summer long program the included talking to strangers, wandering quasi-aimlessly through local parks, and leaving suspicious objects in clandestine locations all in the name of civic engagement. The program, Race to the White House, was a program developed by Global Kids Inc. that relied on geocaching to instigate civic dialogue pertaining to the then upcoming 2012 U.S. presidential election. As the quote and picture that open this study illustrate, students were encountering challenges of engaging with a community that is unfamiliar (and possibly unwelcoming) while also being pushed to explore those unfamiliar spaces. The proximal benefits of geospatial play commingled physical exploration with civic engagement.

Growing in popularity, geocaching is best summarized on the web site, geocaching.com as “a real-world, outdoor treasure hunting game using GPS-enabled devices. Participants navigate to a specific set of GPS coordinates and then attempt to find the geocache (container) hidden at that location.”1 As of 2014, more than two and a half million geocache locations were active around the globe and over six million geocachers were searching for them.

By adopting the geocaching structure in-place by company Groundspeak Inc. (the company that runs geocaching.com and numerous popular mobile apps networked to the website), Race to the White House leveraged geospatial play for civic dialogue. Participants placed items in geocaches around the city of New York that led players to student-created sites about various political issues. The process was one that saw the convergence of mobile technology, geospatial learning, and civic engagement. As mobile technology has increased to the point of ubiquity in the second decade of the 21st century, it is easier than ever to locate, identify, “drop” a digital pin, and otherwise share where we are.

> > Our relationship to digital devices is changing our relationship and understanding of the physical and social world around us. As such, the possibilities for civic learning through geospatial play are a huge area of consideration.

Though there exist other notable examples of geospatial play and forms that mediate GPS-enabled civic lessons (Garcia and Middaugh, forthcoming), this case study focuses on how the Race to the White House utilizes geocaching for civic lessons in proximal and distal contexts.

Description of activities:

There were five basic phases of Race to the White House — these highlighted various aspects of civic learning vis-à-vis “participatory” media (Jenkins et al. 2009).

Students learned basic principles of geocaching.

Students identified and researched several political issues that they felt were of prominent importance to them and would be discussed in the upcoming U.S. presidential election.

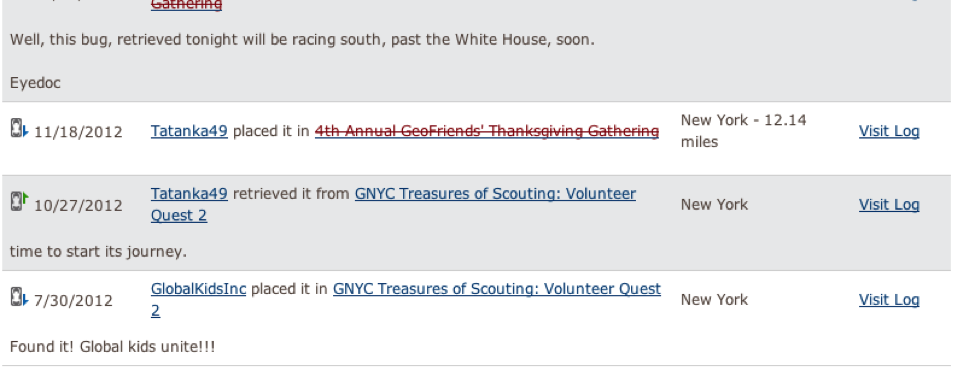

Students produced webpages for each issue and had these pages connected to “travel bugs” placed in geocaches. These physical dog tags had unique codes that allowed geocachers to access online information while also allowing students to track where these devices were placed over time.

Students placed these tracking bugs in myriad local geocaches around New York City.

Students monitored the responses to their trackable travel bugs, the locations the bugs traveled, and how a geocaching audience interacted with civic design in a global scavenger hunt.

Placing the travel bugs throughout New York, students produced websites that encouraged participants to move these travel according to simple rules: if they felt the issue was important for the upcoming election participants should move it closer to the White House. If the issue was not important, it was to be moved farther away. And while the other aspects of this game were powerful signals for youth that their voice was heard, this component of Race to the White House was not as closely adhered to. For instance, while one participant voiced support for increased gun control (an issue taken up by the students), the travel bug-like most in the project-were moved haphazardly (some even off of the continent!). The extending structures of geocaching meant that players took travel bugs to whatever direction they were headed. A family is headed north on a family vacation? The travel bug was headed that way too.

Proximal and Distal benefits of Race to the White House

The summer-long project (with a follow-up activity on election day in November) was one that began with the proximal benefits of mobile technology for geospatial learning: students used the geocaching platform as a means of better understanding the physical and social geographies around them. In this sense, the literal spaces students traversed were read, conveying the spatial literacies (Sheehy and Leander 2010) necessary for a political life in the 21st century. These proximal benefits then adjusted toward more distal concerns; students took up civic issues and dialogue that expanded beyond their immediate and daily lives. Among the issues that students collaboratively researched were the importance of net neutrality, gun control, and the rising costs of college education. Further, in responding to and tracking data, students’ civic engagement telescoped from merely reading their immediate environments to seeing these issues connect to a larger public. The distal benefits of geocaching meant that students saw their voices engage with participants from across the country and-in one instance-internationally.

The GPS technology in this study functioned as merely a tool to encourage student voice; participants in Race to the White House were able to advocate for civic awareness to myriad constituents including their peers, attendees of culminating presentations (hosted at the Brooklyn Public Library), a larger geocaching community, and a general public that interacted with the students in public spaces like parks. With stronger opportunities to connect learning experiences to specific locational contexts, geocaching in this program explored how youth engagement can extend into meaningful aspects of youth’s day-to-day lived experiences. Geocaching, then, highlights how exploration of the physical spaces around youth can instantiate civic lessons. At the same time, these same opportunities allowed youth to see their voices amplified to a broad social network of geocachers. As platforms like geocaching and Race to the White House highlight, geospatial play allows for proximal lessons in the nearby world while also allowing distal benefits via online communication and advocacy.

References

Garcia, Antero and Ellen Middaugh. Forthcoming. “Lost, sweaty, and engaged in dialogue: The civic opportunities of geospatial play.” In #youthaction: Becoming political in the digital age, ed. Ben Kirshner and Ellen Middaugh. Charlotte: Information Age Press,.

Jenkins, Henry, Ravi Purushotma, Margaret Weigel, Katie Clinton, and Alice J. Robison. 2009. Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century. Cambridge: MIT.

Leander, Kevin and Margaret Sheehy. 2004. Spatializing literacy research and practice. New York: Peter Lang.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.