RegulationRoom

Thursday, March 3, 2016

Dmitry Epstein (University of Illinois, Cornell Law School) and Cheryl Blake (Cornell Law School)

Rulemaking, the process used to make new health, safety, and economic regulations, is among the most open and participatory mechanisms in US federal policymaking (Storms 2013). Its formal legal structure establishes robust requirements for transparency and public participation. Rulemakers are required to notify the public of what is being proposed, explain the underlying legal and policy rationales, and provide supporting data. Participation is formally guaranteed by a period during which anyone may comment on a proposed rule. Further, all comments must be reviewed and considered.

However, in practice, meaningful public comment has been highly selective, dominated by industry groups, professional associations, and other well-resourced entities (Kerwin 2003). Both the Bush and Obama Administrations have tried to remediate this and broaden public participation in rulemaking through Regulations.gov, a government-wide rulemaking portal where people can find rulemaking documents and submit comments. Still, observers generally agree that, while the overall number of comments has increased — principally from mass, form-comment campaigns by advocacy organizations (Shukman 2009, 23–53) — effective participation by individuals, small businesses, non-governmental organizations, and other missing stakeholders remains elusive (Balla and Daniels 2007, 46–67; Coglianese 2006, 943–968).

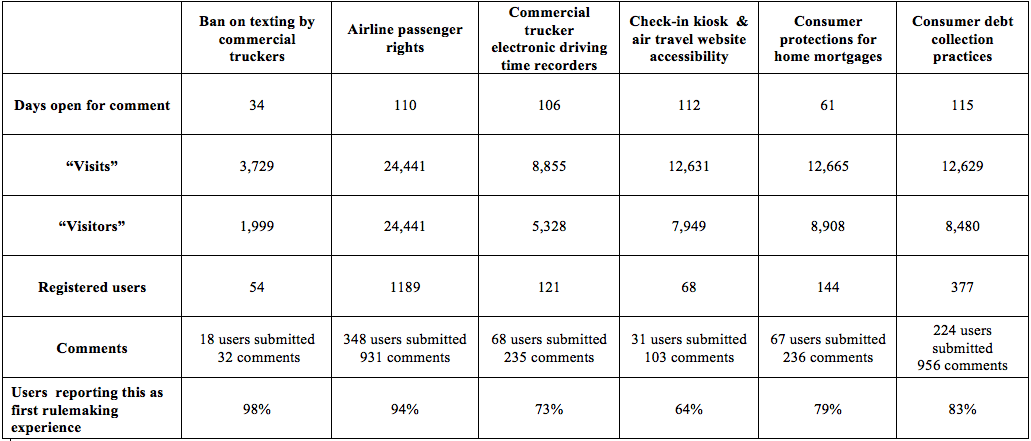

CeRI (the Cornell e-Rulemaking Initiative), a cross-disciplinary group of researchers in law, communication, conflict resolution, and computing and information science, created RegulationRoom with the goal of engaging missing stakeholders in the policymaking process (Storms 2013). As an action-research platform for online civic engagement, RegulationRoom can reach stakeholders nationwide in ways that would not be possible offline. In collaboration with the Department of Transportation and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, six live rulemakings have been hosted on the platform.

The use of web-based tools has long been promoted as a means to lower the cost of public engagement in policymaking and other forms of political activism (Shirky 2008). RegulationRoom is unique, however, in its conception as a socio-technical system. Some civically oriented platforms, such as Ideascale and Change.org, rely primarily on technological tools rather than human support to structure participants’ engagement with policymakers. In contrast, RegulationRoom calls for a more hands-on approach to engagement engineering where technological tools and facilitative engagement practices are closely intertwined.

Drawing on the design-based research paradigm, the RegulationRoom team pursues iterative analysis, design, development, and implementation based on experimentation and observation in the field (Wang and Hannafin 2005, 5–24; Reimann 2011, 37–50). To these ends, we employ a range of mixed methods including web-analytics, surveys, and online ethnographies. Our research so far suggests that supporting broader, better public participation involves a combination of strategically designed technology and human effort over five stages: (1) choosing an appropriate rule, (2) identifying, alerting, and engaging missing stakeholders, (3) information design, (4) facilitative moderation, and (5) closing the loop (Farina et al. 2011, 382–463).

Choosing a rule

Getting public input that is more thoughtful and nuanced than mere expressions of outcome preferences takes time and effort. Not all rulemakings justify this resource investment. Some proposals require specialized technical expertise or impact only a narrow range of stakeholders who are already engaged in the traditional process. Investing in broader public participation is most likely to yield value where there exist (i) one or more substantial groups of missing stakeholders (ii) who are likely to have relevant “situated knowledge”: i.e., information about likely impacts, causation, etc based on first-hand experience with the problems the rule addresses and the circumstances of its implementation (Farina et al. 2012, 123–217).

Identifying, Alerting, and Engaging New Voices

RegulationRoom works with agency partners to identify missing stakeholder groups and determine where and how these groups get information. Targeted conventional and social media outreach, based on this research, tries to motivate participation by (i) explaining how the proposed rule would affect these stakeholders and (ii) emphasizing their legal right to participate and the government’s legal responsibility to review every comment before making a final decision (Farina et al. 2014, 16–40). The ability to recruit participants using social media has provided the research team with opportunities to experiment with the framing of calls to action, with the goal of determining effective frames to motivate engagement in policy deliberation.

Information design

Effective participation is informed participation (Storms 2013). RegulationRoom’s platform design encourages participants to engage with the government’s proposal through a side-by-side format, which features text explaining the proposal on the left and the comment stream on the right. Unlike a traditional blog format, this model highlights the centrality of the proposal text. As such, participants are better able to learn about and critique the agency proposal with specificity. Additionally, participants must attach their comments to particular sections of text (targeted commenting); this helps participants identify sections of interest to them and provide detailed comments about their experiences or concerns related to the issue in that section. Targeted commenting also helps agencies use public input in their decision-making process, because comments are automatically organized by substantive issue. Finally, threaded commenting encourages interactive discussion.

A major information design challenge is that the original rulemaking documents often total hundreds of pages of dense, jargon-filled text. Several techniques are used to render this text into site content that participants can read, understand, and discuss effectively:

Information triage: identifying the most relevant information needed for effective commenting, and packaging it in thematic topic posts of manageable length.

Signposting: cues that help participants rapidly proceed to the issues that interest them most (e.g., an index of topic posts; subtopics with short descriptive titles).

Translation: creating shorter, simpler text using plain-language writing principles.

Layering: using hyperlinks, glossaries, and other hypertext functionality to embed information in ways that allow each participant, at his/her own choice, to get deeper or broader information (e.g., reading the original rulemaking document) — or to find more help than triage and translation have already provided (e.g., definitions; background explanations).

Each of the strategies described above applies existing technological and design tools to a new problem: how to make complex policymaking processes accessible to stakeholders who possess relevant knowledge and concerns, but lack the resources to engage in the traditional process without additional support.

Facilitative moderation

To actually influence the rulemaking outcome, commenters must substantiate claims with facts and reasons, acknowledge competing arguments, discuss alternatives, etc. RegulationRoom provides educational materials about effective commenting in text and video formats, but also relies on human moderators to mentor participants new to the process. Trained in conflict resolution and group facilitation techniques, moderators help participants who lack, or misunderstand, important information about the proposal by replying with clarification or providing links to additional information. To help participants articulate their knowledge, concerns, and arguments as fully as possible, moderators will pose neutral, but probing, questions for more details and the implications of a participant’s comment. Additionally, moderators may: encourage knowledgeable participants to engage more deeply with the government’s analytical documents; point out other issues, and other comments, that relate to the participant’s interests or concerns; and, where necessary, emphasize norms of candid but civil discussion.

Closing the loop

At the close of the comment period, the RegulationRoom team creates a detailed summary of the comments; this is vetted by the community of commenters and submitted to the government as formal public input in the rulemaking process. When a rule is finalized, participants receive an email notice and can visit the site to find a description and text of the final rule, as well as pointers to where RegulationRoom commenters were mentioned.

The RegulationRoom experience is rooted in and enabled through the use of social media. It demonstrates that broader, meaningful public engagement in complex policymaking is possible, but it requires more than mainly technical solutions. Instead, designing for such participation requires thoughtfulness, commitment, and resources on the part of engagement engineers. Unlike less effortful forms of public participation like voting thumbs up or thumbs down on crowdsourced ideas, which rely on aggregation of preferences or sentiment expression, genuine substantive engagement with complex policy proposals builds on socio-technical design that lowers barriers to entry and bolsters effective participation. Though brainstorming and preference aggregation tools have roles to play in civic participation, engagement engineers must ensure that participants have adequate technical and human support to effectively engage in a process — whether it is petitioning, participatory budgeting, or commenting on proposed regulations. Ultimately, they should be guided by the principle that a democratic government should not actively facilitate civic participation it does not truly value.

References

Coglianese, Cary. 2006. “Citizen Participation in Rulemaking Past, Present, and Future.” Duke Law Journal 55 (5): 943–968.

Shirky, Clay. 2008. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations. New York, NY: Penguin, 2008.

Kerwin, Cornelius M. 2003. Rulemaking: How Government Agencies Write Law and Make Policy. 3rd ed. Washington DC: CQ Press.

Farina, Cynthia R., Dmitry Epstein, Josiah Heidt and Mary J. Newhart. 2012. “Knowledge in the People: Rethinking Value in Public Rulemaking Participation.” The Wake Forest Law Review 47 (5): 1185–1241.

Farina, Cynthia R., Dmitry Epstein, Josiah Heidt and Mary J. Newhart. 2014. “Designing an Online Civic Engagement Platform: Balancing “More” vs. “Better” Participation in Complex Public Policymaking.” International Journal of E-Politics 5 (1): 16–40.

Farina, Cynthia R., and Mary J. Newhart. 2013. Rulemaking 2.0: Understanding and Getting Better Public Participation. Washington, DC: IBM Center for the Business of Government.

Farina, Cynthia R., Paul Miller, Mary J. Newhart, Claire Cardie, Dan Cosley and Rebecca Vernon. 2011. “Rulemaking in 140 Characters or Less,” Pace Law Review 31 (1): 382–463.

Farina, Cynthia R., Mary J. Newhart and Josiah Heidt. 2012. “Rulemaking vs. Democracy: Judging and Nudging Participation that Counts,” Michigan Journal of Environmental and Administrative Law 2 (1): 123–217.

Epstein, Dmitry, Josiah Heidt, and Cynthia R. Farina. “The Value of Words: Narrative as Evidence in Policymaking.” Evidence and Policy 10 (2): 243–258.

Wang, Feng, and Michael J. Hannafin. 2005. “Design-Based Research and Technology-Enhanced Learning Environments.” Educational Technology Research and Development 53 (4): 5–24.

Reimann, Peter. 2011. “Design-Based Research.” in Methodological Choice and Design: Scholarship, Policy and Practice in Social and Educational Research, edited by Linda Markauskaite, Peter Freebody, and Jude Irwin, 37–50. New York, NY: Springer.

Balla, Steven J., and Benjamin. M. Daniels. 2007. “Information Technology and Public Commenting on Agency Regulations.” Regulation & Governance 1: 46–67

Shulman, Stuart W. 2009. “The Case Against Mass E-mails: Perverse Incentives and Low Quality Public Participation in U.S. Federal Rulemaking.” Policy & Internet 1 (1): 23–53.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.