Social Media Use and Political Activism in Turkey: 140journos, the Post of Others, and Vote and Beyond

Wednesday, April 6, 2016

Bilge Yesil (College of Staten Island, City University of New York)

During the Gezi Park protests of summer 2013, social media use in Turkey increased sharply portending the affordances of the Internet for horizontal communication, activist organization and political participation. This upsurge was not an ahistorical, apolitical development, but a product of Turkey’s thriving Internet culture as well as the absence of journalistic coverage and ubiquitous government propaganda.

The Internet first became commercially available in Turkey in the late 1990s, and since then the number of users have grown steadily. According to the latest available data, Internet penetration is 45%, with approximately 35 million users, and 70% of them under the age of 35 (“Europe Digital Future in Focus” 2013). Users are especially active on social media: 93% have a Facebook account, and 72% have a Twitter account (“Statista” 2013). YouTube, Instagram, Vine, LinkedIn, Tumblr are among other popular platforms, and blogs, news sites and online forums herald diversity and vibrancy.

> > The Gezi protests started on May 28 as a sit-in against the AKP government’s (Justice and Development Party) plans to commercialize the Gezi Park in central Istanbul, and quickly transformed into a nationwide movement with 3.5 million citizens participating in thousands of events across the country to express their dissatisfaction as well as demands for pluralism and democratic rights (Ozel 2014, 15).

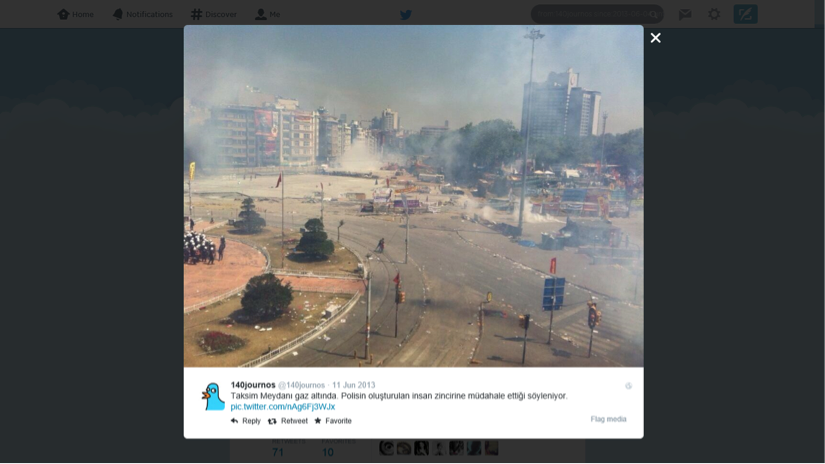

Yet the protests were either ignored by mainstream media from fear of upsetting the government or characterized by partisan outlets as the work of a Western conspiracy. In response, protestors (mostly young and urban) leaned on social media, especially Twitter to fill the information void left by mass media, to counter government propaganda and to compile evidence of police brutality.

Twitter served as the most prominent tool for protestors and information-seekers alike. In the first two days of the protests, at least 2 million tweets mentioning hashtags #direngeziparkı, #resistgezi, #geziparki, #occupygezi were sent out, in coordination with postings on several Facebook pages possessing similar names (“SMaPP Data Report: A Breakout Role for Twitter? The Role of Social Media in the Turkish Protests” 2013). Not only did the number of tweets increase; the number of users did as well — from 1.8 million on May 29 to more than 9.5 million on June 10 (“Gezi Parki eylemlerinin sosyal medya karnesi” 2013).

One particular Twitter account, @140journos stood out as the go-to citizen journalism platform. Named after Twitter’s character limit for messages, 140journos was launched earlier in January 2012 in response to the media blackout concerning the killing of 34 Kurdish villagers by the Turkish air force (“Turkey’s PM pledges” 2011).

Until the Gezi protests, 140journos’ core team, consisting of seven individuals, primarily tweeted from protest rallies and court hearings to inform the public about political events that remained invisible in mass media (“We are All Journalists Now” 2013). When the Gezi protests erupted, 140journos began re-tweeting messages sent in by protestors nationwide.

Indeed, 140journos’ tweets increased from 401 in May 2013 to 2,218 in June, and the number of its followers from 8,000 to 45,000. As of this writing, it has close to 52,000 followers, and the number of volunteers is around 300. The core team remains in charge of aggregating, verifying and categorizing the content generated by these volunteers (Kenner 2013, “Sense of Exhilaration and Possibility” 2014).

In the aftermath of Gezi protests, 140journos’ founders developed a mobile application for Twitter to counter the widespread misinformation from the mass media. The application, currently in beta version, is named Journos and aims to geo-tag user-generated content and embed it with background information (Baykurt 2014).

Another platform that rose to prominence during the Gezi protests was Otekilerin Postasi (“the Post of Others”). The OP was originally launched in late 2012 as a Facebook page under a different name to express solidarity with Kurdish political prisoners. At one point it was shut down by the Facebook administration for having allegedly published pornographic content. The page later re-opened under its current name and now serves as a hub for user-generated content on sensitive social and political issues. During and in the aftermath of Gezi protests, the OP’s Facebook page was closed twice, and had to re-open under a different name on each occasion (Guler 2013). Responding to accusations of censorship, the Director of Facebook Policy in Europe claimed the pages shut down not because of their pro-Kurdish opinion but because they posted content praising the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party), which is considered a terrorist organization by Turkey, the U.S and the E.U. (Basaran 2013).

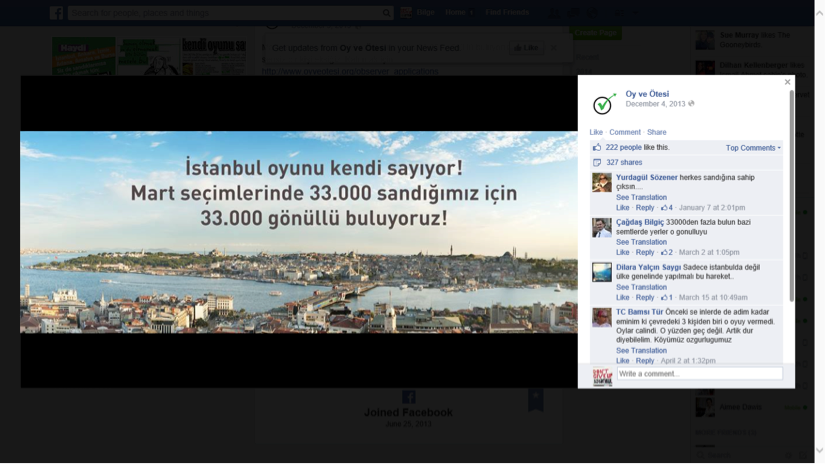

After the Gezi protests waned, the affordances of social media were evident once again during the local elections of March 2014. In the period leading up to the elections, a number of civic initiatives emerged to increase voter turnout, monitor polling stations and prevent electoral fraud. They were mainly driven by the AKP’s increasing authoritarianism in the post-Gezi period and by widespread rumors about the party’s attempts to rig the elections. Among these initiatives 140journos and Oy ve Otesi (“Vote and Beyond”) particularly stood out. Oy ve Otesi was launched by eight volunteers to recruit, train and organize election monitors in Istanbul. Reaching out to the public via Twitter and Facebook, the initiative managed to enlist close to 30,000 volunteers who monitored 95% of polling stations in Istanbul on Election Day.

> > The other prominent actor in the coordination of monitoring and verification of ballot box tabulations was 140journos.

On Election Day, 140journos urged citizens to send photographs of ballot box tabulations under the hashtag #tutanak. The team of volunteers aggregated nearly 6,000 received photos and compared them to official results published by the Election Board, and reported 250 irregularities (Baykurt 2014).

140journos also developed a new web-based application to detect and report tabulation irregularities. Named Saydirac (“The Counter”), the application aims to enable citizens to enter data into the system which will then be compared to official results. 140journos launched Saydirac on June 1, 2014 when repeat elections were held in three provinces. One of 140journos’ co-founders, Cem Aydogdu notes that they hope Saydirac will facilitate active participation of citizens: “This is a tool designed to prevent a handful of individuals from shouldering the burden, a tool to prevent citizens from remaining on the sidelines and instead take responsibility for their own votes.”

140journos used Saydirac again on August 10, 2014 — the day of the presidential election. It was joined by other initiatives that also organized volunteers and used social media to monitor and verify the votes. Among them were @Oy ve Otesi (Vote and Beyond), @SandikBasindayiz (We are at the Polls) and @TRnin Oylari (Turkey’s Votes) and its local branches in six major cities. Before the election, these groups organized close to 10,000 volunteers to work as “ballot box monitors,” posted YouTube training videos for them, and even set up 1–800 numbers in case they needed assistance. The presidential election was not as heated as the local elections back in March due to several reasons, most prominently because of low voter turnout. Accordingly, social media activity levels remained low compared to March elections.

Discussion

The literature on the role of the Internet and digital communications regarding democratization, and social, political and economic change has generally centered on a dichotomy between cyber-utopians and skeptics. Whereas the utopian view holds that the Internet enables the emergence of a citizen-based, participatory democracy (Negroponte 1995, Dyson 1997, Shirky 2011), skeptics focus on the issues that emanate from corporate colonization, data mining, surveillance, digital divides, and nation-state censorship laws, and question the impact of connectivity on social movements and change (McChesney 2000, Margolis and Resnick 2000, Coleman and Blumler 2009, Morozov 2011). This split between the cyber-utopians and skeptics has deepened further in the aftermath of the protests in Iran in 2009 and the Arab uprisings in 2011 as the former group declared the Internet and social media “tools of change” that could defy authoritarian regimes (Diamond 2010, Stepanova 2011, Allagui and Keubler 2011, Sullivan 2009, “The Iranian Uprisings” 2013) while the latter interrogated the import of digital tools and instead emphasized the social, cultural, and political roots of the protests and the human agency behind them (Sreberny and Khiabany 2010, Deibert and Rohozinski 2011, Morozov 2011, Christensen 2011, Newsom, Lengel and Cassar 2011). This “conceptual gridlock” or “false dichotomy” between optimist and pessimist perspectives has inevitably led to the discussion of digital activism simply in terms of its effectiveness while ignoring other questions (Aouragh and Alexander 2014, Echchaibi 2013). To remedy this limited framework, researchers began to consider the Internet and forms of digital activism not merely as tools but rather as spaces and paid attention to the co-existence and co-evolution of technologies, practices and actors or the convergence of online and offline activism, for example (Khamis and Vaughn 2011, Trere 2012, Castells 2012, Aouragh and Alexander 2014, Echchaibi 2013).

To make sense of the aforementioned civic initiatives in Turkey, I adopt a similar line of thinking, and focus on their creative and insurgent capacities instead of evaluating their potential to dismantle the existing power structures. Here I draw upon Echchaibi’s argument that forms of digital activism, even in the absence of revolution, are significant because they create spaces of dissent. They show how “people confront power” through “a series of creative improvisations and flows, which may or may not lead to structural change” (2013, 865). It is this “act of doing” that is significant and deserves attention, not the end result (the defiance of the regime, the dismantling of the status quo, etc). Therefore the emphasis should be on the “sustained and disciplined online presence” of digital practices not their potential to subvert the system. In a similar vein, Aouragh and Alexander focus on the import of “spheres of dissidence” and discuss the Internet as a “space” of political activity rather than a tool. In light of these explorations, I consider the digitally-enabled initiatives in Turkey as noteworthy expressions of dissent, participation and civic engagement especially when one considers the broader media and political systems in which they operate.

Similar to other national contexts such as Iran, Russia, China to mention just a few, state control of the Internet looms large in Turkey. With the steady increase in the Internet use since the mid-2000s, the state’s efforts to confine the networked public sphere have amplified as seen in the filtering and blocking of online content, the construction of a strict legal framework, and more recently the demonization and banning of social media platforms (e.g. Twitter and YouTube bans of March 2014). So far, 140journos, Oy ve Otesi and others have not been faced with any blocking attempts or overt obstruction from the state (The Facebook pages of Otekilerin Postasi were closed numerous times, but one must remember that it was not upon the request of the Turkish government but by the company administration’s own initiative). The absence of state intervention can be attributed to a couple of factors: The ruling AKP party has cemented its hold over power to the extent that it does not deem these initiatives threatening at all. Or it is using them as “safety valves” so anti-government activists can express their frustration online or via these initiatives instead of organizing mass protests. It is also likely that the government is exploiting the presence of these initiatives so it can claim that there is freedom of speech in Turkey and ward off criticism.

It must also be noted that 140journos, Oy ve Otesi, Saydirac and TRnin Oylari bespeak the convergence of online and offline activism as well as the evolving relationships between traditional mass media and the Internet. For example, 140journos relies on its network of volunteers who post words and images from the street, while Oy ve Otesi, Saydirac and TRnin Oylari foster and build upon the physical presence of individuals at polling stations. Also, the input of these initiatives, be it the dissemination of news or the reporting of voting irregularities, are generally picked up by newspapers, television channels and online news sites. Therefore, it is important to analyze these initiatives not merely in terms of the Internet and digital connectivity, but within the framework of the larger media ecosystem, spatiality and mediation (McCurdy 2011, Castells 2012, Costanza-Chock 2012, Gebaudo 2012).

References

Allagui, Ilhem and Johanne Keubler. 2011. “The Arab Spring and the Role of ICTs.” International Journal of Communication 5: 1435–1442.

Aouragh, Miriam and Anne Alexander. 2014. “Egypt’s Unfinished Revolution: The Role of the Media Revisited.” International Journal of Communication 8: 890–915.

Castells, Manuel. 2012. Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Christensen, Christian. 2011. “Discourses of Technology and Liberation: State Aid to Net Activists in an Era of ‘Twitter Revolutions.’” Communication Review 14: 233–253.

Coleman, Stephen and Jay Blumler. 2009. The Internet and Democratic Citizenship: Theory, Practice and Policy. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. 2012. “Mic Check! Media Cultures and the Occupy Movement.” Social Movement Studies: Journal of Social, Cultural and Political Protest 11 (3–4):1–11.

Deibert, Ronald and Rafal Rohozinski. 2011. “Liberation vs. Control: The Future of Cyberspace.” The Journal of Democracy 21 (4): 43–57.

Diamond, Larry. 2010. “Liberation Technology.” Journal of Democracy 21 (3): 69–83.

Dyson, Esther. 1997. Release 2.0: A Design for Living in Digital Age. New York: Broadway.

Echchaibi, Nabil. 2013. “Muslimah Media Watch: Media Activism and Muslim Choreographies of Social Change.” Journalism 14 (7): 852–867.

Gebaudo, Paulo. 2012. Tweets and the Streets: Social Media and Contemporary Activism. London, UK: Pluto Press.

Khamis, Sahar and Katherine Vaughn. 2011. “Cyberactivism in the Egyptian Revolution.” Arab Media & Society13:1–37.

Margolis, Michael and David Resnick. 2000. Politics as Usual: The Cyberspace Revolution. London: Sage.

McChesney, Robert. 2000. “So Much for the Magic of Technology and the Free Market.” In The World Wide Web and Contemporary Cultural Theory, edited by Andrew Herman and Thomas Swiss, 5–35. New York: Routledge.

McCurdy, Patrick. 2011. “Theorizing Activists’ ‘Lay Theories of Media’: A Case Study of the Dissent Network at the 2005 G8 Summit.” International Journal of Communication 5: 619–638.

Morozov, Evgeny. 2011. The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom. New York, NY: Public Affairs.

Negroponte, Nicholas. 1995._ Being Digital_. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Newsom, Victoria Anne, Lara Lengel and Catherine Cassar. 2011. “The Arab Spring — Local Knowledge and the Revolutions: A Framework for Social Media Information Flow.” International Journal of Communication 5: 1303–1312.

Ozel, Soli. 2014. “A Moment of Elation: The Gezi Protests/Resistance and the Fading of the AKP Project.” In The Making of a Protest Movement in Turkey: #OccupyGezi, edited by Umut Ozkirimli, 7–24. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Shirky, Clay. 2011. “The Political Power of Social Media: Technology, the Public Sphere, and Political Change.” Foreign Affairs 90 (1): 28–41.

Sreberny, Annabelle and Gholam Khiabany. 2010. Blogistan: The Internet and Politics in Iran. London: I.B. Tauris.

Stepanova, Ekaterina. 2011. “The Role of Information Communication Technologies in the Arab Spring.” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo. http://www.gwu.edu/~ieresgwu /assets/docs /ponars /pepm_159.pdf.

Trere, Emiliano. 2012. “Social Movements as Information Ecologies: Exploring the Co-evolution of Multiple Internet Technologies for Activism.” International Journal of Communication 6: 2359–2377.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.