Strike Debt and the Rolling Jubilee: Building a Debt Resistance

Wednesday, March 30, 2016

Erhardt Graeff (University of Colorado)

From The Debt Resisters’ Operations Manual:

> > “There are countless ways to ‘strike’ debt: demanding a people’s bailout and an end to corporate welfare; collectively refusing to pay illegitimate loans; targeting and shutting down collections agencies, payday lenders, or for-profit colleges; regulating loan speculators out of business; reinstating limits on usurious interest rates; defending foreclosed homes; fighting tuition hikes and school budget cuts; resisting austerity policies; fighting militarism, which accounts for half of our nation’s discretionary spending; organizing debtors’ associations and unions; and more. On the constructive side, building an alternative economy run for mutual benefits is a long-term goal.” (Strike Debt 2014, 213)

Growing out of Occupy Wall Street, Strike Debt has been working since May 2012 to build a social movement through various forms of media and market-based activism under the banner of “debt resistance.” They cite the history of Biblical jubilees that cancelled debt to normalize society (Graeber 2011), the debtor movement like El Barzon in Mexico (Caffentzis 2013), and “mortgage strikes” by Empowering the Strengthening Ohio’s Peoples (Strike Debt 2014, 93), to make an intellectual and moral argument for why debt resistance is justified against the contemporary system of debt that in their analysis causes dehumanizing shame and suffering. They describe debt as a weapon and a web that catches you, such that as soon as you pay off one loan you are indebted for another reason (Graeff and Bhargava 2014).

Prehistory of Strike Debt

In the midst of Occupy Wall Street (OWS) on October 23, 2011 at ContactCon, artist and activist Thomas Gokey, inspired by his own struggles with student debt, participation in “war tax resistance,” and conversations with others at Zuccotti Park, proposed building a reverse KickStarter or “Kick-Stopper,” a platform for organizing a large scale debt strike by collecting pledges from participants and coordinating the payment of debt into escrow rather than to big banks (2011a; n.d.). It went on to win acclaim as one of the most actionable ideas at the conference (Jaffe 2011). While Kick-Stopper was in development via a mailing list, Gokey has started working on a related idea for buying and forgiving debt with Adbusters’s Micah White (Gokey 2011b; White 2014). White had imagined the idea back in 2009, and later received input from David Graeber, who wrote about the history of debt forgiveness “jubilees” in his book Debt: The First 5,000 Years (White 2014).

Back at Zuccotti Park, the Occupy Student Debt Campaign (OSDC) formed from assemblies involving sociologist and activist Andrew Ross (Larson and Smith 2014). Growing out of Occupy Wall Street’s Education & Empowerment Working Group, OSDC developed a debt refusal pledge campaign, which they launched November 21, 2011. The idea was that signers pledged to default on their debt once one million other signers did the same. OSDC distributed the pledge and related information and collected stories of indebtedness through their website. Their focus on debt refusal as an explicit alternative strategy to legislative action differentiated OSDC from prior initiatives like Student Loan Justice (n.d.), and gained enough notoriety to merit the inclusion of their “debt strike” as a new tactic in Andrew Boyd’s Beautiful Trouble (Jaffe & Skomorovsky 2012). However, the OSDC pledge was ultimately unsuccessful.

In response to OWS’s disaggregation after actions on May Day 2012, Occupy Theory, the working group of OWS publication Tidal held a series of assemblies in Washington Square Park. One of the early assemblies co-organized with OSDC and Free University was on Education and Debt in solidarity with student strikes in Montreal; it attracted many OWS affiliated organizers and participants looking at mortgages, education, or other debt-related and social justice issues (Hiscott 2013; Strike Debt 2014; Larson & Smith 2014). The resonance of the assembly and subsequent conversations indicated to the organizers in attendance that there was common interest in broadening their analyses to look at the whole debt system (Larson & Smith 2014). This was the genesis of Strike Debt.

Building the Movement

Strike Debt’s Facebook page was created June 6, and its website’s domain names were registered on June 11–12. Their first events were “debt assemblies” in parks, starting on June 11, 2012 in Washington Square Park (McKee 2012). The debt assemblies gave a safe space for debtors to come and share their stories of indebtedness and build community and solidarity. They also continued their analysis of the debt system, and started to draft the Debt Resister’s Operations Manual (DROM) to offer advice on how to escape all types of debt and urge individuals to join in collective action, in a debt resistance movement (Ross 2013).

During Strike Debt’s first few weeks, a friend recommended to organizer Aaron Smith that he contact Gokey (Larson and Smith 2014). Smith and a former OSDC organizer who had previously spoke to Gokey invited him to travel from Syracuse and pitch his idea for buying debt on the secondary market, like debt collectors do, and then cancelling it (Ibid.). Despite reservations by other Strike Debt organizers who thought the idea was too capitalistic, they pushed ahead with meeting Gokey, hoping the tactic could at least raise awareness (Ibid.).

By mid-July, the idea of the Rolling Jubilee, then known as the “debt fairy” campaign, was added to Strike Debt’s game plan (McKee 2012). From the beginning, they argued it was not an end-game strategy, as Strike Debt organizer Yates McKee noted in a July 13 essay,

> > “While not a structural solution — and not applicable to student loans — scaled up it could become what David Graeber imagines as a “moving jubilee” capable of both garnering media attention around debtors’ struggles and taking business away from the intermediary companies that profit from hounding and penalizing those unable to pay.” (Ibid.)

Gokey had already successfully tested the debt-buying idea using $500 of his own money. To effectively scale the action, Strike Debt reached out to lawyers and accountants for help with the details, and set a goal of raising $50,000 with the hope of buying $1M worth of debt at the going rate of ~5 cents on the dollar (Larson and Smith 2014).

Strike Debt continued to organize debt assemblies over the summer (Ross 2013), building toward OWS’s anniversary on September 17, 2012 (S17), where they would officially launch the DROM. Strike Debt was deeply involved with the planning of and media activism around S17, where one of the “quadrants” was dedicated to the theme of “debt”; they hoped to unite Occupy Movement participants around the issue (Taylor 2012; Graeber 2012; Konczal 2012a).

The Rolling Jubilee and its Limits

Following S17 and the launch of DROM, Strike Debt focused on planning a launch for the Rolling Jubilee to coincide with the November 15, 2012 anniversary of OWS’s eviction from Zuccotti Park. Its Facebook page had already been registered August 14, and its website’s domain names were registered September 26–27. On October 22, they shared a screenshot of the teaser page on their website via Facebook.

Returning to the successful tactic of story sharing employed by OSDC and the debt assemblies, on October 29, Strike Debt started curating stories arguing for debt resistance on Tumblr. A larger social media bomb via Twitter and blogs was planned to launch the Rolling Jubilee using a mailing list of organizers from the Occupy Movement’s network of encampments — a strategy inspired in part by the Kony2012 campaign’s successful construction and activation of on-the-ground networks to make their video go “viral” (Larson and Smith 2014).

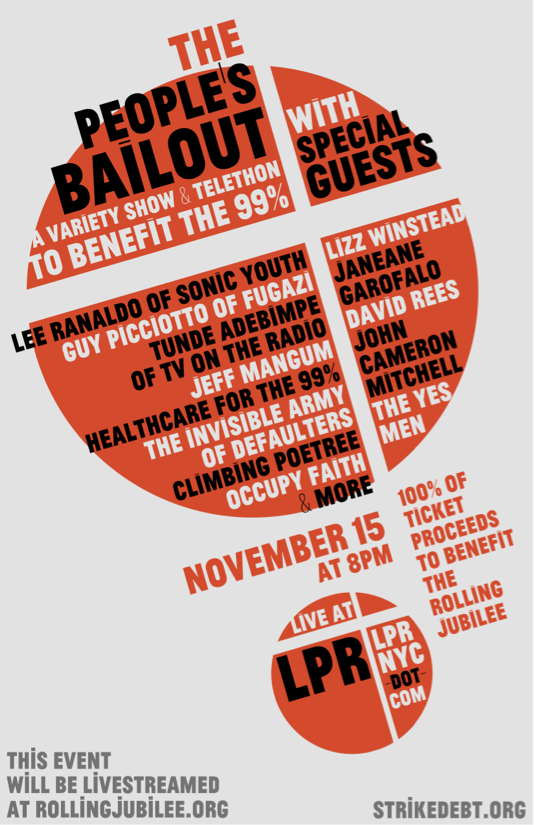

The launch was designed as a “telethon” entitled “The People’s Bailout,” featuring musicians and comedians taking the stage and a livestream simulcast — all ticket proceeds went to the Rolling Jubilee fund and online donations were tallied with updates punctuating the acts. The social media bomb was planned for a week ahead of time. They created a promotional video and poster for the event, and drafted a press release for their network for promotional use. Unexpected social media success came on November 8 as co-organizer and co-host of the telethon David Rees posted the announcement to his well-followed Tumblr blog the night before the bomb; it piqued the interest of actor and writer Wil Wheaton who re-blogged it, putting the press release in front of his large audience of followers. Within 48 hours, the online donations surpassed the $50,000 goal (Larson and Smith 2014).

By the end of its first push, the Rolling Jubilee took in $435,000 (Tepper 2012), well surpassing its goal. However, critics dismissed the Rolling Jubilee as a “gimmick,” arguing it was at a scale too small to have impact and was a distraction from more useful tactics like educating people about strategic bankruptcy (Henwood 2012; Smith 2012). They also questioned its ability to build a movement through debt forgiveness (Konczal 2012b). Strike Debt organizers reiterated that it was never meant to be a large-scale solution (Ross and Ackerman 2012; Ross and Taylor 2012), as McKee had noted early on. Instead, Ross and Taylor’s piece in The Nation emphasized that the Rolling Jubilee was “an act of solidarity and an opportunity for public education,” and introduced the broad set of debt resistance strategies and the long-term vision of a system of positive credit through mutual aid (2012).

These response articles and interviews also publicized the creation of Strike Debt chapters in cities and on campuses across the country, inspired by the DROM (Ross and Taylor 2012; Tepper 2012). This is Strike Debt’s real end-game strategy: build a networked social movement around debt resistance by correcting the information asymmetry between the lenders and the indebted while promoting a wide variety of actions.

The Rolling Jubilee stopped collecting donations on December 31, 2013. The donations totaled $701,317. And as of the writing of this case study, they had purchased and “abolished” $14,734,569.87, with one more jubilee announcement on the way. The first four debt purchases, detailed on the “Transparency” page of the Rolling Jubilee website, went to medical debt, the accrual of which is arguably rarely the fault of the debtor, which helps reinforce Strike Debt’s moral argument against the debt system.

Next Steps

With the Rolling Jubilee ending, the Strike Debt organizers I spoke to in May 2014 say they will miss the massive media attention delivered by the debt buys, but they are eager to focus on creating a more sustainable structure for Strike Debt and building the on-the-ground network of debt resisters (Larson and Smith 2014). They want to grow the number of chapters, especially on college campuses, and get the DROM, which has been expanded into a full book, into more hands. They continue to analyze the debt system and write reports to support their intellectual and moral argument (Graeff and Bhargava 2014). Additionally, they are exploring new forms of action and public education, currently working with an NYU law student to develop “debt clinics” (Ibid.).

Market-based Activism, Media Activism, or Both?

In his book Code and other Laws of Cyberspace, Lawrence Lessig contends that there are four ways contemporary society is regulated: law, norms, markets, and architecture (2006). Ethan Zuckerman argues that these also represent opportunities for citizens to affect change in complex systems by treating each of them as levers (2013). Strike Debt as a debt resistance movement and an offshoot of Occupy Wall Street has a particular focus on the market-based lever, generally used to punish corporations by affecting the cost of doing business. The goal of debt resistance as practice by Strike Debt is to undermine and destroy the system of lenders that prey on debtors, ideally drying up their market through non-participation. The Rolling Jubilee is a tactic that tried to subvert the system by using its own market structure to cancel debt. But as the organizers confess, this is symbolic; its utility is its ability to draw attention to the issue, like a creative event in the service of media activism.

Analyzing Strike Debt’s tactics using Albert Hirschman’s framework of exit, voice, and loyalty, debt resistance looks like an exit from the relationship with big banks and the debt system (1970). This is the long-term goal of an alternative economy for mutual benefit. But this is not easy to achieve because of the laws, norms, markets, and architectures that govern the system and everyone who touches it. Thus, it becomes an exercise in voice, confronting the system designed to bind people to it, as in the “web” metaphor Strike Debt uses. This demands media activism to affect norms and perhaps laws — fortunately, one of the great successes of the Occupy Movement has been to move anti-capitalism and class inequality into the “sphere of legitimate controversy” from the “sphere of deviance” to use Daniel Hallin’s terms for how the media covers different issues (1986).

If Strike Debt can succeed where OSDC failed as Gokey aspired with Kick-Stopper, by building a large enough network of debt resisters willing to form a debtor’s union and refuse to pay up, then perhaps we will see a full exit from the debt system and a “salvaging” of popular democracy to quote Ross (2013). At the very least, Strike Debt’s tactics for both media activism and market-based activism add to a creative repertoire for adjusting Lessig’s and Zuckerman’s levers, pioneered by contemporary networked social movements.

REFERENCES

Caffentzis, George. 2013. “Reflections on the History of Debt Resistance: The Case of El Barzon.” South Atlantic Quarterly 112 (4): 824–30. doi:10.1215/00382876-2345315.

Gokey, Thomas. n.d. “A Debt Strike Vision.” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1o6J0ITGJReByTHjX9B1UyLOTcyRMHcih-8psAw7G_0g/edit.

2011a. “Kick-Stopper,” October 23. ContactBBS. Internet Archive. December 20, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20111220011757/http://forum.contactcon.com/discussion/33/kick-stopper.

2011b. “Volunteer Programmer Needed for a Debt Forgiveness Project”, November 1. https://groups.google.com/d/topic/debt-strike-kick-stopper/8H8pA91_sDo/discussion.

- “Debt Strike Update”, August 20. https://groups.google.com/d/topic/debt-strike-kick-stopper/_d2dssJHlF8/discussion.

Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: The First 5,000 Years. New York: Melville House. 2012. “Can Debt Spark a Revolution?” The Nation, September 5. http://www.thenation.com/article/169759/can-debt-spark-revolution.

Graeff, Erhardt, and Rahul Bhargava. 2014. “Strike Debt and the Moral Argument for Debt Resistance.” MIT Center for Civic Media Blog. http://civic.mit.edu/blog/erhardt/strike-debt-and-the-moral-argument-for-debt-resistance.

Hallin, Daniel C. 1986. The Uncensored War: The Media and Vietnam. New York: Oxford University Press.

Henwood, Doug. 2012. “The Problem with (Strike) Debt.” Jacobin, November 14. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2012/11/the-problem-with-strike-debt/.

Hirschman, Albert O. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hiscott, Rebecca. 2013. “Defined by Debt: How the Strike Debt Movement Redefined Occupy.” Truthout, May 30. http://truth-out.org/news/item/16671-defined-by-debt-how-the-strike-debt-movement-redefined-occupy.

Jaffe, Sarah. 2011. “Debtor’s Revolution: Are Debt Strikes Another Possible Tactic in the Fight Against the Big Banks?” AlterNet, November 3. http://www.alternet.org/story/152963/debtor%27s_revolution%3A_are_debt_strikes_another_possible_tactic_in_the_fight_against_the_big_banks/?page=entire.

Jaffe, Sarah, and Matthew Skomarovsky. 2012. “Debt Strike.” In Beautiful Trouble: A Toolbox for Revolution, edited by Andrew Boyd, 24–26. New York: OR Books. http://beautifultrouble.org/tactic/debt-strike/.

Konczal, Mike. 2012a. “On the Occupy/Strike Debt ‘Debt Resistors’ Manual.”Next New Deal. http://www.nextnewdeal.net/rortybomb/occupystrike-debt-debt-resistors-manual.

Mike. 2012b. “Keep Calm and Get Excited About the Rolling Jubilee.” Next New Deal. http://www.nextnewdeal.net/rortybomb/keep-calm-and-get-excited-about-rolling-jubilee.

Larson, Ann, and Aaron Smith. 2014. “Interview with Strike Debt Organizers” Interview by Erhardt Graeff.

Lessig, Lawrence. 2006. Code Version 2.0. New York: Basic Books. http://pdf.codev2.cc/Lessig-Codev2.pdf.

McKee, Yates. 2012. “With September 17 Anniversary on the Horizon, Debt Emerges as Connective Thread for OWS.” Waging Nonviolence, July 13. http://wagingnonviolence.org/feature/with-september-17-anniversary-on-the-horizon-debt-emerges-as-connective-thread-for-ows/.

Ross, Andrew. 2013. “Democracy and Debt.” Is This What Democracy Looks Like? http://what-democracy-looks-like.com/democracy-and-debt/.

Ross, Andrew, and Seth Ackerman. 2012. “Strike Debt and Rolling Jubilee: The Debate.” Dissent, November 13. http://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/strike-debt-the-debate.

Ross, Andrew, and Astra Taylor. 2012. “Rolling Jubilee Is a Spark — Not the Solution.” The Nation, November 27. http://www.thenation.com/article/171478/rolling-jubilee-spark-not-solution.

Smith, Yves. 2012. “Occupy Wall Street’s Debt Jubilee: A Gimmick with Tax Risk.” Naked Capitalism. http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2012/11/occupy-wall-streets-debt-jubilee-a-gimmick-with-tax-risk.html.

Strike Debt. 2014. The Debt Resisters’ Operations Manual. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

Taylor, Astra. 2012. “Occupy 2.0: Strike Debt.” The Nation, September 5. http://www.thenation.com/article/169760/occupy-20-strike-debt.

Tepper, Fabien. 2012. “The ‘People’s Bailout’ Was Just the Beginning: What’s Next for Strike Debt?”YES!, December 13. http://www.yesmagazine.org/new-economy/peoples-bailout-just-the-beginning-whats-next-strike-debt-rolling-jubilee.

White, Micah. 2014. “On the Origins of the Rolling Jubilee (Solving a Movement Mystery with History).” Boutique Activist Consultancy. May 3. http://www.activistboutique.com/leaderless-revolution/origin-rolling-jubilee.

Zuckerman, Ethan. 2013. “The ‘Good Citizen’ and Effective Citizen.” …My Heart’s in Accra. http://www.ethanzuckerman.com/blog/2013/08/19/the-good-citizen-and-the-effective-citizen/.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.