The ‘Solutionistic’ Logic of the National Day of Civic Hacking

Friday, March 25, 2016

Ingrid Erickson (Rutgers University)

On January 22, 2013, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy released a blog post cum press release titled “Roll Up Your Sleeves, Get Involved, and Get Civic-Hacking,” written by Brian Forde, Senior Advisor to the U.S. CTO for Mobile and Data Innovation, and Nicholas Skytland, Program Manager of NASA’s Open Innovation Program (Forde & Skytland, 2013). In it, they encouraged “citizens across the Nation” to “join together to improve their communities and governments as part of the National Day of Civic Hacking.” Beyond the mandate embedded in the title, the authors describe the first NDoCH as “ . . . an opportunity for software developers, technologists, and entrepreneurs to unleash their can-do American spirit by collaboratively harnessing publicly-released data and code to create innovative solutions for problems that affect Americans.” By March of that year, Intel had joined as the event sponsor. According to Brandon Barnett, Director of Business Innovation at Intel Labs, Intel saw the event in similarly patriotic terms as a way “to invent to applications and services that combine people’s digital information with open, public data for the common good” (Barnett, 2014).

> > The partnership formed by Intel and the White House is notable for many reasons, not least of which is how it appeared to legitimize a new form of civic engagement. For many, hacking is still considered a primarily negative, nefarious activity — so the White House sanctioning it made people notice.

Within a narrower group of folk, such as the Maker community (in which hacking is understood to be the unfettered and creative of use of resources to create new and innovate products), this embracing of civic hacking might have made more sense. In this case, it hinted at opportunism. Either way, the case of the National Day of Civic Hacking and the rising movement of civic hacking that now surrounds it, creates an opportunity to question the relationship between civic values and socio-technical practice in our current digital age.

The White House’s rhetoric excerpted above marks an impassioned move by government to engage and be engaged by citizens of every type and persuasion. Yet, in equally clear terms it is also obvious here that participation will be measured by a rubric of improvement and innovation. Ideally, Forde and Skytland note, “this summer will mark the first time local developers from across the Nation unite around the shared mission of addressing and solving challenges relevant to OUR blocks, OUR neighborhoods, OUR cities, OUR states, and OUR country” [emphasis added]. Morozov (2013) defines such an emphasis on improvement and problem-solving as ‘solutionism’ — -an ethos that he ascribes liberally to technologists in Silicon Valley who, he believes, labor under the naive yet well-funded belief that social problems and other organizational and civic issues can be ‘solved’ with the correct, targeted attention and the application of salient technical acumen. Nowhere was a solutionistic air more on display than the particular National Day of Civic Hacking event that I attended in New York City in 2013. This particular hackathon was dedicated to addressing the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, specifically the question of how preparation as well as cleanup might have been improved by potential technological intervention. Organized by local victims — both technically-skilled and not — this event drew upwards of 100 people at its peak, many of whom were simply curious to see what a civic hackathon might be like. It began with a lively discussion of the events of Superstorm Sandy in which many people shared their own particular horror stories, most quite compelling and motivating.

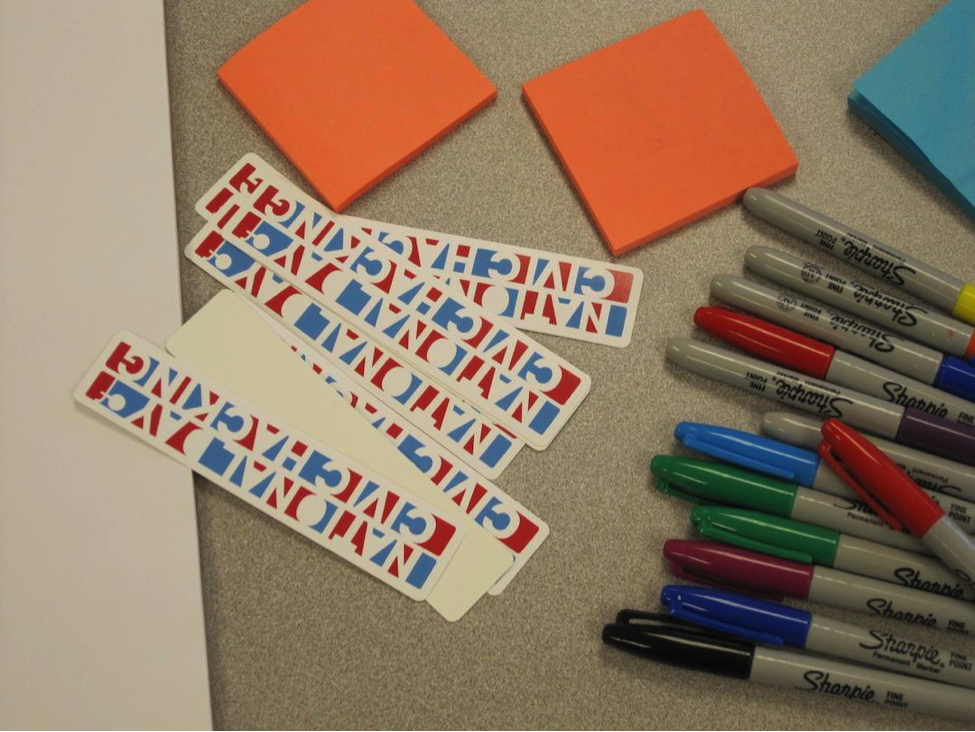

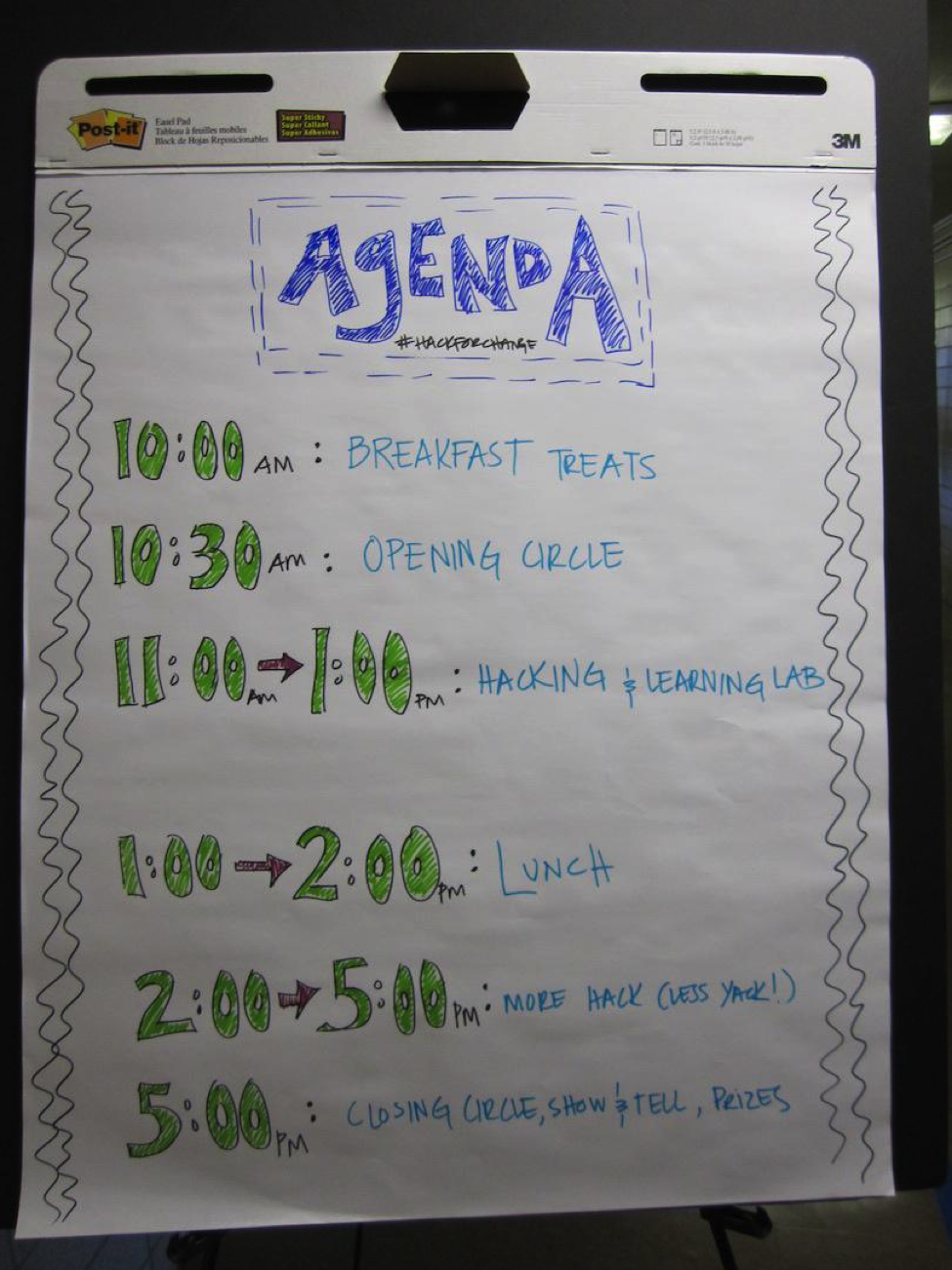

Despite overt rhetoric otherwise, what soon happened was an interesting social sorting. Once they had told their stories, the ‘community members’ slowly drifted away, unable to participate in the overarching logic of the day, “Less yack, more hack.” Gradually the coders in the room organized themselves into separate projects and got to work. There was little discussion or negotiation beyond the initial sharing period; rather, what quickly came to dominate the room was the competitive feeling of a charrette as the minutes began to tick away. The end of the day resulted in a presentation of six projects (in various states of completion). What was most apparent to this onlooker were not the products of the day’s labor, but the fact that, even in this catholic group, success was measured in rather stark terms: technical functionality trumped all other values.

The case of civic hacking is worth contemplating with regards to civic engagement in several ways. In the most positive sense, the allegiance between citizens and governments from local to the national level represents a means of direct engagement that is paired only by citizens’ ability to vote. Governments are opening their resources such as databases (albeit in highly curated instances) without apparent direction or circumspection — a form of apparent DIY civic engagement. However, this move simultaneously appears to be a sign that governments feel the need to outsource their lack of technical skill or innovative insight to the ready pool of willing citizens willing to work (and provide value) for little to no cost. Yet this is possibly the least of the consequential issues in play here.

More significantly, the practices of civic hacking appear to be reifying a new type of super-citizen who, along with a small set of similarly proficient individuals, is beginning to secure the means to decide what is or isn’t civic. Hackers’ instantiation of projects, delivered according to a logic of rational efficiency, sets in motion a prioritization of civic values that equates importance with the ability to be built. Thornier matters that require messy deliberation or longer gestation periods risk not only being overlooked but also undervalued. Thus, as much as there is cause to celebrate the increasing porosity of these new models of civic engagement, we also need to be sure to keep on yacking while carrying on hacking. Anything less is merely software engineering.

References

Barnett, Brian, May 6, 2014, “Catalyzing Open Innovation with the Largest U. S. Hackathon,” National Day of Civic Hacking Blog, http://hackforchange.org/catalyzing-open-innovation-with-the-largest-u-s-hackathon/

Forde, Brian, and Skytland, Nicholas, January 23, 2013 (1:39 p.m.), “Roll Up Your Sleeves, Get Involved, and Get Civic-Hacking,” Office of Science and Technology Policy Blog, http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2013/01/22/roll-your-sleeves-get-involved-and-get-civic-hacking

Morozov, Evgeny. To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism. New York: Public Affairs, 2013.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.