The Values and Activities of Making Civic Media

Monday, February 12, 2018

The Values and Activities of Making Civic Media

by: Gabriel Mugar

Government agencies, news outlets, and community-based organizations (CBOs) play an important role in mediating civic life, however most are now struggling with their relevance in an increasingly networked and polarized society.

In this climate of distrust, we conducted a study to learn how activists and civic institutions are leveraging media and digital technology to rebuild and reimagine new approaches to civic discourse and action.Through our conversations with over 40 civic media practitioners in Boston, Chicago, and Oakland, we provide a way of identifying and evaluating media and technology designed to facilitate democratic process.

In this post we highlight some of the key findings from the full report, which you can find here.

Prioritizing the Social in Media

The practitioners we spoke with looked to media and technology not to solve a particular problem, but to facilitate discourse and build relationships around a problem space. By encouraging this socializing and network building around a problem, we saw that their work reflect an ethic of care, an essential part of citizenship that orients people towards an understanding that citizenship is the practice of how we work with others to take care of the world we live in.

The emphasis on building relationships and discourse around problems also reflects the design value of meaningful inefficiencies, where the use of technology and media for purposes of organizing is not intended to create a streamlined and prescriptive approach to solving civic challenges, but is instead meant to encourage collaboration, socializing, and problem solving that go beyond the imagination of what the designer intended.

These two values sit at the core of of how we came to define the work of those we interviewed as civic media practice. Civic media practice is then the work of making media and technology that supports democratic process. The work is in itself a democratic proposition, requiring people to come together and understand and negotiate their collective interests within a problem space in such a way that they improve how they communicate and collaborate to address those problems.

Civic Media Takes Time

How practitioners do the work of moving from an act of creation or adoption of new media or technology to one of shared goals and visions is central to civic media practice. All the practitioners we spoke to described this process as directly confronting power structures, sometimes involving social difference such as race, class, and gender, and other times involving organizational hierarchies.

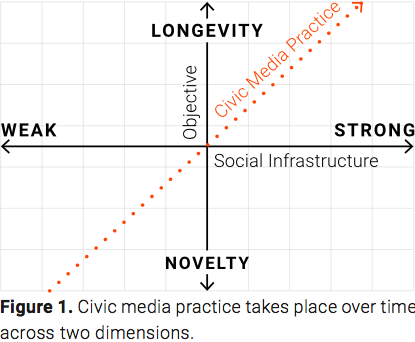

As such, civic media always takes place over time. In this graph, we provide a method of plotting a snapshot of a project along two dimensions: the horizontal of social infrastructure and the vertical of objective.

Social infrastructure is defined as the “people, places, and institutions that foster cohesion and support.” If a group has strong existing relationships with a community, they will be on the right side of the plot. If they are brand new to a community, they will be on the left.

The second dimension of civic media practice is the objective — how practitioners think about the impact of their work (i.e. impact in the short-term or long-term). Some projects are designed with novelty in mind (i.e. a social media campaign designed to garner quick attention), and some with longevity in mind (i.e. a publicly designed mural on a community center).

The Four Activities of Civic Media

What defines civic media practice, distinct from other forms of media practice, are a set of four activities that characterize this striving towards the top right quadrant in the graph. Practitioners work to situate themselves within a network of stakeholders with shared interests, and have made long-term impact a core objective in their work. The work of practitioners doesn’t need to begin there, but it needs to aspire towards it. The four activities include:

Network Building: Civic media practitioners place a premium on convening people as part of their practice. They often place value on informal gathering spaces that bypass some of the strictures of formal meetings or input sessions.

Holding Space for Discussion: The work of striving for common good in making civic media involves defining a shared set of values and anticipated benefits. Our research reveals that this is supported by holding space for discussion. Practitioners do this by holding regular meetings and workshops where the interests and needs of various stakeholders are articulated, shaping subsequent steps in the media making process.

Distributing Ownership: This describes the work of positioning the constituents of a problem space to take it over and further define the characteristics of a civic media project. In our study, the work of distributing ownership appeared when practitioners outline clear pathways to participation, actively encouraging a power dynamic where stakeholders take the reins of the practice, or when practitioners adopt an open source ethos to their work, sharing knowledge and encouraging appropriation and repurposing of practice.

Persistent Input: Practitioners understand the context of their issues by not simply asking people what they think, but doing so from a position of stability, continuity, and trust: asking once, and then being in the same place to ask again. This persistence is reflected in long-term relationships between practitioners and the communities they work in. This practice of understanding the problem through persistent relationships is not only what motivates the design of a particular story or project, it is the value driving the entire practice.

Measuring progress

In the report we argue that practitioners creating and deploying media and technology for civic aims need to turn their attention to process over outcome. We offer a series of questions to encourage reflection on a practitioners progress along the axes of social infrastructure and objective.

The first step is to plot the starting point for a project. This requires assessing social infrastructure. Here, practitioners can consider what level of connection they have with the real or perceived end users, how strong their current relationships with stakeholders are, and if or for how long they have worked with the target community.

The assessment of objective is based on the stated intentionality of the practitioner. Here, a practitioner can ask if their project is intended to be short-lived or long-term or if the media or technology developed will remain in the community for an extended period of time.

With the starting point in place, practitioners can set up regular intervals throughout the project lifespan to see how their project is moving along the graph. Doing so can be done by asking questions related to the four activities:

Network building: Have you developed new connections in the community you’re working in?

Holding space for discussion: Are you taking steps to engage people outside of your immediate network?

Distributing ownership: Are you creating opportunities for stewardship by stakeholders?

Persistent input: Are you engaged in long term conversations with stakeholders?

What else is in the report?

In addition to providing more detail around the activities and measurement of civic media practice, we also provide two case studies from our research. We apply our process of measurement to each case to demonstrate how civic media practitioners moved their projects towards the top right quadrant of the graph, emphasizing longevity and strong social infrastructure in their work.