Tracking Traveling Paper Dolls: New Media, Old Media, and Global Youth Engagement in the Flat Stanley Project

Friday, March 4, 2016

Katie Day Good (Northwestern University)

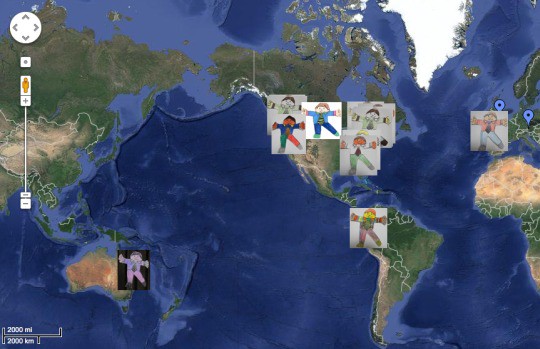

In the last two decades, thousands of students around the world have communicated with each other using homemade paper cutouts called Flat Stanleys. They are participants in the Flat Stanley Project, a letter-writing and digital literacy campaign launched in 1994 that has since “gone viral” in the education world. The Flat Stanley Project has taken many forms, but it typically involves a young person creating his or her own paper doll — a Flat Stanley (or Flat Stella or Stacie) — and sending it, along with a blank journal and note of introduction, to a faraway student, relative, or celebrity in the mail. Recipients then take the paper figures on “adventures” in their schools, communities, and workplaces, photographing them in front of notable landmarks, documenting their travels in the journal, and often gathering local mementos before returning the materials to the sender. In addition to carrying out these postal exchanges of physical materials, many FSP participants make use of digital tools to track Flat Stanley’s journeys and share them with a wider audience online, including email correspondence, blog entries, YouTube videos, Google Maps, and photos posted on social media websites.

With its emphasis on combining material and virtual forms of exchange, the FSP is a unique artifact of educational media culture at the turn of the millennium, evidencing both the integration of digital media tools into instruction and the increasing emphasis on cultivating new literacies and global citizenship among youth. While educators’ discourses about the FSP often focus on its value as a project with technological applications and a novel form of global virtual exchange, many also praise its “old media” elements―e.g., handwritten letters and journals, material mementos, and, most importantly, the handmade, mobile avatar of the child in the Flat Stanley doll―for establishing a palpable sense of connection among far-flung youth. The aim here is to suggest that the FSP’s preservation of these material and localized forms of international exchange, deployed in conjunction with efforts to involve students in the participatory networking potentials of virtual and digital technology, offers a unique and promising model for cultivating global youth engagement in the digital age.

The FSP began in 1994 when Dale Hubert, a 3rd-grade teacher in Ontario, Canada, read Flat Stanley, a 1964 children’s book by Jeff Brown in which a young boy is flattened by a falling bulletin board and subsequently mailed to California in an envelope.

The story inspired Hubert to assign his students to create their own paper Flat Stanleys and exchange them with faraway peers in the mail, an activity that he believed would not only promote writing and literacy, but also engage them with the new technology of the Internet. After creating a simple HTML website, Hubert began coordinating exchanges of Flat Stanleys between Canadian and American schools. Soon, his website became a hub for teachers and students to post pictures of Stanely’s travels and share curriculum ideas. Within a few years, Hubert was inundated with requests from educators around the world seeking to participate in the project. By 2005, Flat Stanleys were being exchanged by as many as 10,000 classes in 62 countries. They had ridden aboard Air Force One and the space shuttle Discovery, visited Tibet, Antarctica, and the Taj Mahal, and posed with Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush.

As the FSP has grown along with the surge of new media devices in education, it has been lauded for its adaptability to teaching the new literacies of the 21st century. Teachers now use the exchange of Flat Stanleys not just to improve students’ proficiencies with new technology―whether by conducting web projects, creating and navigating digital maps, tracking traveling items online through geocaching, or participating in cross-cultural conversations through videoconferencing ―but also to develop students’ global awareness, intercultural competencies, and interest in government and international affairs. Educators also highlight the collaborative nature of the FSP’s virtual exchanges, drawing parallels between the participatory, networked features of the digital media involved and the active global citizenship they hope to cultivate in students through its use.

Despite this enthusiasm for the digital applications of the FSP, discourses about the material aspects of the exchange―the letters, dolls, and souvenirs sent through the mail―suggest that physical objects continue to provide a meaningful complement to virtual tools in expanding children’s global networks and knowledge in the 21st century. For instance, some have mused that the paper-based FSP revives the “lost art” of letter writing and the excitement of waiting for, and eventually opening, a package that has made a long journey. Against the backdrop of instant connectivity and communicative convenience afforded by the Internet, the mailing and hand-to-hand passing of physical artifacts and handwritten texts between contacts conveys a valuable sense of intentionality, communities, and care. Teachers have also cited the value of students handling tactile objects that traveled from afar, or seeing the dolls they made themselves standing in front of faraway landmarks, in giving them a “vicarious tour” of the world. While Hubert has suggested that the FSP is effective in both its digital and material variations, he has also reflected on the “pleasantly low-fi” aspect of the mail exchanges and observed how the handmade avatar is especially effective at creating “shared experiences” among distant people because “[s]tudents can write about how they made the Stanley, explain any rips or damage in a creative way, and talk to the other person using Flat Stanley’s voice.”

The global circulation of paper Flat Stanleys is representative of a trend that folklorist Lynne McNeill calls “serial collaboration,” or “the process of passing an object from person to person and place to place in order to see how far around the world it can travel.” McNeill argues that in a world where virtual relations are increasingly the norm, the exchange of material objects creates meaningful, physical connections among distanced people and “reassures people that the other beings they interact with ephemerally are still present and real―as tangible and as solid as the object sent out.” These tangible aspects of material exchange are worth keeping in mind as educators move to integrate new technologies into lessons on global citizenship and engagement. Perhaps a combination of “new” and “old” media devices can enhance virtual exchanges by anchoring them in a tangible sense of connection and community between far-flung youth.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.