Webabludatel: A Russian Electoral Observation App

Friday, March 25, 2016

Ksenia Ermoshina (Center for Sociology of Innovation, France)

WebNabludatel is a Russian application for Android and iPhone that aims to help electoral observers to report on all cases of fraud, producing citizen-generated statistics on electoral falsifications. This application was developed in response to massive falsifications during legislative elections of December 2011, in order to prepare, educate and arm new independent observers for Presidential elections, which took place on the 4th of March 2012.

The idea of WebNabludatel was first publicly expressed on the 22nd of December 2011 on Habrahabr, the most popular Russian collaborative blog of developers and IT specialists, when Ilya Segalovitch, ex-CTO of Yandex proposed an idea of creating a mobile “observer’s digital diary.” This diary would help observers with surveying the voting process and documenting fraud. The post was seen 1709 times, liked 117 times and commented 398 times, with lots of proposals from developers and UI designers giving first spontaneous ideas of application architecture and menu. Four days later a young programmer and entrepreneur, CTO of a well-known Russian IT-company “Progress Engine” Alexey Poimtsev creates a Google group dedicated to this “electronic diary” project, inviting “any developers using Ruby on Rails” to collaborate with him. In few days, front-end developers for Android an iOS mobile app are found, the tasks are distributed and an open code repository is created on GitHub. The work took 1 month and a half and the total cost of the project was only 200 dollars, with members of the team investing their own money to pay for hosting and servers. In total, 17 persons worked on the development of the application. The code of the application is open and available at GitHub. The whole story of WebNabludatel’s creation can be characterized in terms of “stigmergic collaboration”, described by several scholars as one of the main mechanisms of self-organization within open-source and “civic hacking” communities based on indirect incentives (“artefacts”) and mutual aid (Heylighen 2007; Eliott 2006; Robles and al. 2005).

Apart from technical expertise, legal competences were required to build this application in accordance with the law and with observers’ experience. That is why the team collaborated with two NGOs “Golos” and “Grazhdanin Nabludatel,” both specialized in defending voters’ rights and preparing observers for the elections. The application had to be not only technically efficient, but also based on a solid legal ground. Developed by a hybrid team of technical and legal experts and activists, WebNabludatel is a techno-juridical instrument (Contini and Lanzara 2008) with legal code being translated into programming code, and rules and norms of electoral procedures inscribed into the interface of the application.

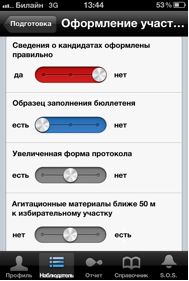

Though, to be translatable into a mobile interface, legal norms had to be functionally simplified. So, the UI designers worked with lawyers from “Golos” to adapt several hundreds of pages of electoral code and “cut” the observation practice on major steps. These steps are represented in the menu of the app in a chronological order, guiding the user throughout the elections day: from checking empty urns early in the morning to counting bulletins and signing protocols during the night after the elections. Every step has been translated into a simple question with only “yes/no/no information” answers possible. This standardization of observers practice, allows an automatic treatment of the whole volume of gathered data, and a representation of this data according to the type of fraud, location and other criteria. This standardization by design has, we argue, a certain “multiplication” effect (Ermoshina, 2014): it helps to transform individual observers’ experiences into parts of a bigger movement of building crowdsourced proofs database of elections illegitimacy.

An observer and user of WebNabludatel, shares her user experience of the app:

> > “The observer’s guide was very well done, structured as a sequences of questions. For example, the voting starts — what should I observe? I must verify that the voting boxes are empty and properly closed, that all observers are registered and so on. You only put yes or no, it is useful as it helps you stay concentrated I remember when at the end of the day women from electoral commission started shaking the voting box, turning it upside down before opening it, I knew it was illegal, and I fixed and filmed it with my app. But the app can’t do anything when the fraud is happening outside of the polling station, when people vote at their places. In my case, it was the major problem, and we could not film or fix it with the app.”

So, even if the app is useful to fix visible fraud, it can not really prevent or control everything. It is first of all conceived to organize observer’s activity, instruct and empower him legally.

Mobile technology plays here a crucial part, as it comes in response to a specific user experience: need for immediate reaction, simplified and structured information available “at hand,” geolocation function that helps to map data, photo and video features to document the event. An SOS-button was equally integrated into the interface, giving observers a possibility to ask for lawyers’ help in one click, in case of aggression or illegal expulsion from the polling station.

> > Taking into consideration the absence of Wi-Fi (or its intentional blockage) on many polling stations, the app has been made totally independent from the Internet: the inner memory of the app allows a user to fulfill the check-list and stocks all the data until he finds a place with a good connection.

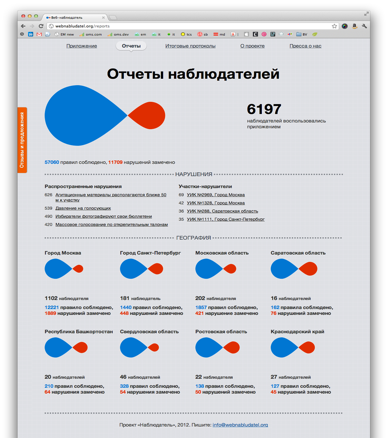

The application was used by 6197 persons during the presidential elections of the 4th of March 2012, 11709 frauds were registered, classified and geolocated. According to these data “Golos” started legal proceedings against some of the falsificators.

The application had a certain international success, winning the German “Deutsche Welle Blog Awards” with 549 voices as the “best usage of technologies for social good.” The code source of the app was reused by Ukrainian and Moldavian activists.

WebNabludatel app, in the context of distrust of Russian citizens towards traditional political institutions, can be considered as an instrument of counter-democracy, as described by Rosanvallon (2008). It attempts to give citizens a technical instrument of crowdsourced surveillance and collective control over governments, transforming users into “participatory sensors” (Goodchild 2007; Boulos 2011) by cutting a global problem, that of illegitimacy of elections, into micro tasks and steps. The application aims at democratizing observers’ skills and expertise by incorporating them into a simple and easy-to-use app, giving equal access to the procedure of observation to all users condition considered by Michel Callon as one of the basic features of technical democracy (Callon and al. 2009).

References

Boulos Kamel, B. Resch, David Crowley, John Breslin, Gunho Sohn, R. Burtner, William Pike, Eduardo Jezierski, and Kou-Yu Slayer Chuang. 2011. “Crowdsourcing, citizen sensing and sensor web technologies for public and environmental health surveillance and crisis management: trends, OGC standards and application examples.” International Journal of Health Geographics 10:67.

Callon Michel, Pierre Lascoumes, Yannick Barthes, and Graham Burchell. 2011. Acting in an Uncertain World: An Essay on Technical Democracy. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, and London, UK.

Contini, Francesco, Giovan Francesco Lanzara. 2009. ICT and Innovation in the Public Sector. Palgrave Macmillan.

Elliott, Mark. 2006. “Stigmergic Collaboration: The Evolution of Group Work.” M/C Journal 9 (2). .

Goodchild, Michael F. 2007. “Citizens as sensors: the world of volunteered geography.”_ GeoJournal_ 69 (4): 211–221

Ermoshina, Ksenia. 2014. “Democracy as pothole repair: Civic applications and cyber-empowerment in Russia”. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 8(3), article 4. doi: 10.5817/CP2014–3–4

Heylighen, Francis and Carlos Gershenson. 2003. “The Meaning of Self-organization in Computing.” IEEE Intelligent Systems 18 (4): 72–75

Heylighen, Francis. 2007. “Why is Open Access Development so Successful? Stigmergic organization and the economics of information.” In Open Source Jahrbuch, edited by B. Lutterbeck, M. Bärwolff and R. A. Gehring. Lehmanns Media.

Robles, Georgio, Juan Julian Merelo, and Jesus M. Gonzalez-Barahona. 2005. “Self-Organized Development in Libre Software: a Model based on the Stigmergy Concept,” Proc. 6Th International Workshop on Software Process Simulation and Modeling,http://www.libresoft.es/webfm_send/44.

Rosanvallon, Pierre. 2008. Counter-Democracy: Politics in an Age of Distrust. Cambridge University Press.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.