Youth Data Literacy as a Pathway to Civic Engagement

Friday, March 4, 2016

Erica Deahl (Civic Data Design Lab, MIT)

The growth of ubiquitous big data, and its uses across a wide range of sectors, has made the ability to work with data an essential tool for active citizenship and a critical skill for many professions. Yet the educational system is not preparing young people with the skills they need to participate in a data-rich society. Few young people — indeed, few adults — have interacted with data, let alone feel empowered in their interactions. This knowledge deficit presents an important opportunity to shift the dialogue about data through youth education. Teaching young people to work with data, and to become “data literate,” can enable them to understand and participate in civic issues, prepare them for a range of professions, and equip them to think critically and ethically about data.

The City Digits project seeks to take advantage of this opportunity by integrating data literacy and civic education into the school curriculum, using digital tools and a student-driven pedagogical approach. It is a high school math class and an accompanying web application (citydigits.mit.edu) that provide opportunities for youth to explore data, develop data literacy, and engage in analysis and debate around civic issues. The first module, Local Lotto, focuses on the topic of the New York State Lottery and its social impact on New York City’s underserved communities.

The project was developed by an interdisciplinary team: math education researchers from Brooklyn College, civic technology designers and urban planners from MIT’s Civic Data Design Lab, and public policy educators from the Center for Urban Pedagogy, a not-for-profit education and advocacy organization (National Science Foundation). The team worked closely with high school math teachers from New York City public schools, who gave feedback throughout the process and piloted the curriculum in their classes.

City Digits was designed to be implemented in New York City high schools in low-income areas, where mathematics scores are persistently low and students have few opportunities to participate in civic issues in or out of school.

City Digits addresses this disparity by grounding mathematics concepts in authentic data and real-world issues — making them more relevant and engaging, and encouraging students to take an active role in exploring issues affecting their communities.

Piloting City Digits

The curriculum was piloted twice in 2013 with 100 high school juniors and seniors at a public school in one of Brooklyn’s poorest neighborhoods. The first implementation was in April 2013 within an “advisory” class of 15 high school sophomores. The curriculum and technology were revised based on the results of the pilot and a larger pilot was conducted in November 2013 with one teacher and his four 12th-grade mathematics classes totaling 95 high school seniors (Williams 2014).

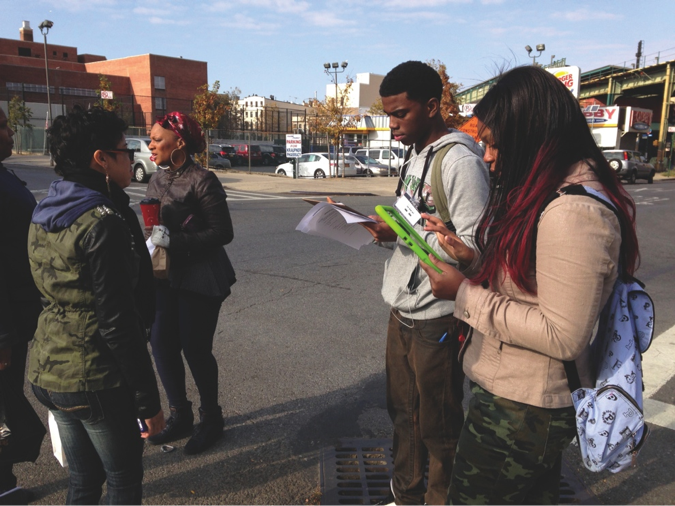

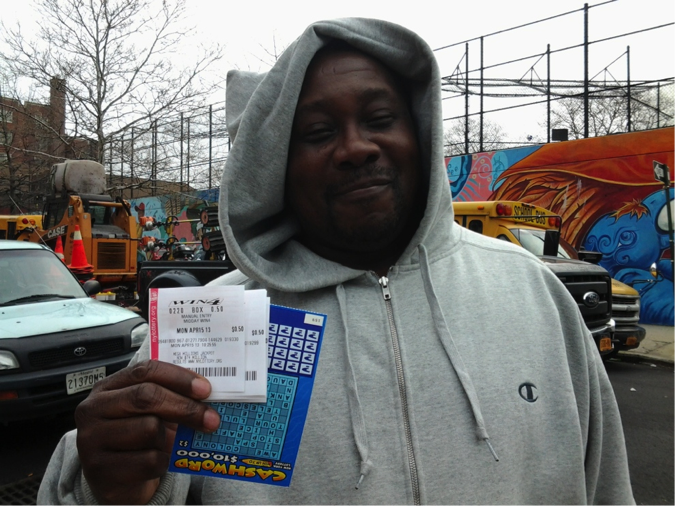

The curriculum was divided into three units, each of which was supported by the web application. First, students divided into small teams to collect local qualitative data about their community’s opinions on the lottery by conducting interviews with pedestrians and lottery ticket retailers in their neighborhood, using the web application on tablets (Fig. 1). Students wanted to find out why and how often people played the lottery and see how local businesses thought the lottery was impacting the neighborhood. Using the tablet allowed students to easily navigate, collect data in the field, and instantly publish geo-located results. Students discovered many stories from people for whom the lottery is a central part of their lives. For instance, one man said he spends $50 on the lottery every week because is unemployed and wants to support his family (Fig. 2).

In the second unit, students used an interactive map to explore and understand the impact of the lottery on communities. The map showed lottery spending and winning data at a citywide level and at a highly localized level, visualizing data from stores that sell lottery tickets. The map also shows lottery spending as a percentage of each neighborhood’s median household income. The geographic representation enabled students to identify patterns and analyze the large-scale effects of the lottery as a system, by building on geographic knowledge they already had about their city. For example, students quickly picked up on one of the most striking trends, that lottery players in low-income neighborhoods spend a significantly higher proportion of their income on lottery tickets than players in higher-income neighborhoods.

In the final phase of the curriculum, students combined knowledge drawn from interview data and map data to assess the lottery’s social impact. In doing so they drew on the skills they developed and the information they collected during previous phases of the project. Students shared, debated, and published their opinions about the lottery, creating multimedia narratives to illustrate their reflections using maps, interviews, and other evidence to support and structure their arguments. They expressed a diverse range of opinions in their work. Some thought, “The lottery is a tax to manipulate and mislead the mathematically illiterate.” Others proposed a new system: “Each borough needs to have their own lottery, that way the money that is being spent gives back to their own community.” And some had the opposite opinion, that “The lottery is a great way to raise money for schools.”

Challenges and Outcomes

At the start of the program, many of the students were unable to read a map, a problem the researchers had not anticipated. In a pre-pilot focus group, they discovered that students did not have a sense of city geography, and that many could not locate the borough of Brooklyn on an unlabeled city map. Others had not mastered foundational mathematics skills on which the data analysis relied, and this caused some students to struggle with sections of the curriculum.

Despite these challenges, City Digits’ greatest successes were to support students in exploring a social justice issue through data and to engage students who did not normally participate in class. During the post-pilot focus group, the students told us they enjoyed the opportunity to explore data individually and in groups, rather than listening to a teacher lecture. One student said he had “never seen a class even work like this ever, ever before… Everyone was so interested. I didn’t think that was possible.” Students said that the class was engaging because the issues were “real” to them, and in contrast to typical school assignments, called on them to wrestle with complex arguments (Williams 2014).

Exploring local data offered diverse opportunities for engagement, especially for English Language Learning students, who were not normally outgoing in class discussions. Since the high school where we conducted the pilot was in a neighborhood that was heavily Spanish speaking, students who were native Spanish speakers were positioned to become leaders in their groups. One student who is a recent immigrant and was quiet during the initial class sessions became outgoing and animated during the data collection day. She conducted the majority of the interviews and was excited to contribute during the classroom interview debrief.

By the end of the course students were able to interpret data, develop their own arguments, and use a combination of quantitative and qualitative data to support them. They combined personal accounts from their neighbors and broader patterns of lottery spending to reach their own judgments on the inequalities and benefits of the system. This experience led students to develop strong opinions — by the time students had created their arguments, they felt like experts on the topic. There was a dramatic transformation between the first class and the last, as students became more confident speaking up and sharing their opinions in class.

This motivation to share their opinions extended beyond the classroom — some students told us that they had discussed the topic with their friends and families. One student said he has been showing his mother his work and that he convinced her to stop buying lottery tickets. Five of the students from the pilot volunteered to teach an abbreviated version of the class to groups of high school math teachers during the City Digits team’s training sessions. Most of these students were not the highest performers in their class during the pilot, yet they have gone on to master the content they are teaching and become articulate and enthusiastic presenters. The City Digits pilot showed that even students who were disengaged in a school setting were more than willing, when given the opportunity, to engage with complex issues facing their communities, and to actively participate in finding solutions.

If you like what you just read, please click the green ‘Recommend’ button below to spread the word! More case studies and calls for submissions are on the Civic Media Project. To learn more about civic media, check out the book Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice.